As I mentioned in a previous post, Boston is a city of made land. Once a peninsula, it was connected to the mainland by a narrow isthmus that sometimes flooded during high tides. The city grew and expanded by creating new ground.

An Engineering Marvel

The most famous of these projects was the filling of the Back Bay. This nineteenth-century engineering marvel created hundreds of acres of new land by filling in a tidal marsh with gravel deposited by the glaciers. Today, the Back Bay is a beautiful, vibrant neighborhood. It houses upscale residences, historic churches, profitable businesses, and public institutions such as the magnificent Boston Public Library.

An Eye-Opening View

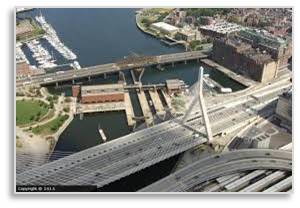

Fortunately, the Charles River Dam and Lock system provides some protection against smaller increases.This system, built in 1978, blocks the mouth of the river where it meets the harbor between Boston’s North End and Charlestown neighborhoods.

The dam was created to control flooding in low-lying areas, particularly the Back Bay. It transformed the unsightly tidal mudflats of the lower Charles into the attractive and much-used, fresh-water Charles River Basin.

The dam rises 12.5 feet above sea level, which means the five-foot view of flooding probably would not happen. The ends of the dam might have to be reinforced against an increase of 12 feet but that would be easier and cheaper than allowing the river to flood.

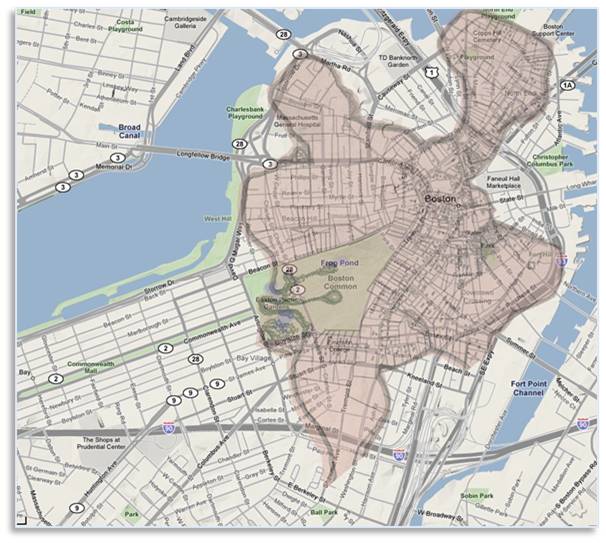

The Back Bay Underwater

At 12 feet, the Esplanade, Storrow Drive, Beacon Street and the eastern end of Commonwealth Avenue would be underwater, as would both the Boston and Cambridge approaches to the Massachusetts Avenue Bridge. That would mean no more Fourth of July concerts by the Boston Pops at the Hatch Memorial Shell.

I hope the engineers at MIT are working on how to protect their campus. Maybe the folks who wear a “brass rat” can build a big beaver dam around the Great Dome.

The Drowned City and Made Land

In the harbor view, the building behind the Boston Harbor Hotel with the curved glass wall is the J.J. Moakley Federal Courthouse on Fan Pier where gangster Whitey Bulger is currently being tried. Behind that rises the vibrant new Seaport District where houses, hotels, restaurants, and the Boston Convention & Exhibition Center are creating a new and exciting neighborhood. All of this also exists because of made land.

And it’s not just Boston. Sea-level rises of these magnitudes will create the same destruction in any major city that’s on a harbor or near the ocean. I hope Boston’s authorities are planning ahead for such eventuality, though. If not, in a few years I might be giving a Boston by Foot tour of the Victorian Back Bay via glass-bottom boat.