Every once in a while, a meme goes around on Facebook that makes fun of Boston street names. It’s very long and addresses a variety of topics in a somewhat humorous fashion but, in regard to street names, it says the following:

“There is no school on School Street

No court on Court Street

No dock on Dock Square, and

No water on Water Street.

Back Bay Boston streets are in alphabetical ordah: Arlington , Berkeley , Clarendon, Dartmouth , etc.

So are South Boston streets: A, B, C, D, etc.

If the streets are named after trees (e.g. Walnut, Chestnut, Cedar) you are on Beacon Hill.

If they are named after poets, you are in Wellesley.”

Boston Street Names Today

Now, today three of those comments remain accurate because they haven’t changed over time.

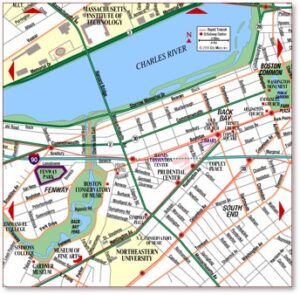

The Back Bay:

When Arthur Delevan Gilman designed the Back Bay, he named the north-south streets for the dukes of England in alphabetical order starting at the Public Garden: Arlington, Berkeley, Clarendon, Dartmouth, Exeter, Fairfield, Gloucester, and Hereford. So, if you know your alphabet, you can always look at a cross-street sign to figure out where you are.

When Arthur Delevan Gilman designed the Back Bay, he named the north-south streets for the dukes of England in alphabetical order starting at the Public Garden: Arlington, Berkeley, Clarendon, Dartmouth, Exeter, Fairfield, Gloucester, and Hereford. So, if you know your alphabet, you can always look at a cross-street sign to figure out where you are.

These named streets start at the Public Garden because the Back Bay was filled from east to west, ending at what was then Gravelly Point and is now Massachusetts Avenue.

Why would Mr. Gilman have chosen this naming scheme? Well, prior to designing the Back Bay, he visited and took inspiration from Westbourne Terrace in Hyde Park, England. Several of the street names there resemble those here, including Gloucester Square.

South Boston:

Southies’ streets, likewise, still follow the letters of the alphabet. This naming scheme, while neither poetic nor historical, works quite well. It requires no change. Besides, I’ll take the alphabet over the name of yet another self-aggrandizing Massachusetts politician any day.

Beacon Hill:

Yes, the streets of Beacon Hill have the names of trees. That harks back to Rev. William Blackstone, who was the first European resident of the Trimount (Beacon Hill, Pemberton Hill and Mount Vernon). Rev. Blackstone laid out his farm and orchards on the hill because of the plentiful springs there. When in 1795 the Mount Vernon Proprietors bought land on the south slope from the painter John Singleton Copley and developed it into a residential neighborhood, they named the streets for the trees on Rev. Blackstone’s farm.

Boston Street Names Back Then

But Boston wasn’t built in a day. It started with the Puritans landing in 1630 and grew from there. After centuries of land making, wharfing out, and shifting neighborhoods, the city has over time grown a very different coastline and skyline.

The same evolution applies to Boston street names. If we unpack the comments in the Facebook meme, we can discount them. Why? Because those street names were as accurate back then as they seem deceptive now.

School Street:

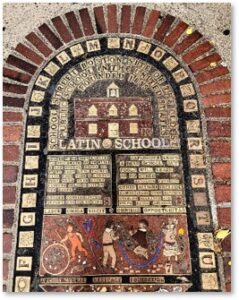

Today, you will not find any school building on School Street. But that street once held the first publicly funded school in America. In 1635, the Puritans erected a two-story schoolhouse on a spot that now stand in front of Old City Hall. In addition, they introduced the innovative concept of a free public school for all, whether rich or poor. Back then, of course, the “all” mostly meant free white boys.

Today, you will not find any school building on School Street. But that street once held the first publicly funded school in America. In 1635, the Puritans erected a two-story schoolhouse on a spot that now stand in front of Old City Hall. In addition, they introduced the innovative concept of a free public school for all, whether rich or poor. Back then, of course, the “all” mostly meant free white boys.

A mosaic embedded in the sidewalk by Lilli Ann Killen Rosenberg called “City Carpet” commemorates that structure. Back then, the street was named Latin School Street and the school, which today stands on Avenue Louis Pasteur, is the Boston Latin School.

Court Street:

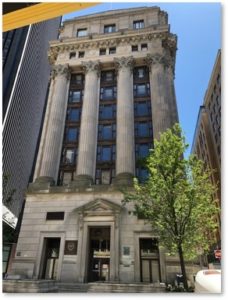

Today, Court Street lacks a single court building, but it formerly was the location of a courthouse, starting in 1635. The Boston Gaol stood on Prison Street until that thoroughfare was widened in 1708 and renamed Queen Street. A new building replaced that one in 1704 and others followed, after a series of fires.

Boston built a more substantial granite courthouse from 1833 to 1836 designed by Solomon Willard in the Greek Revival Style. The four Doric columns of granite in its façade weighed 25 tons each. That lasted until 1809 when the courthouse moved to Pemberton Square, where it remains today. The City Hall Annex replaced it. Queen Street became Court Street after 1776, when royalty became unpopular in Boston.

Dock Square:

The name of this space generates a certain confusion as the meaning of “dock” has changed over time. Today we think of a dock as a wooden structure that juts out into a body of water. In the seventeenth century, however, a dock constituted a body of water in between piers. In the case of the Town Dock, the term defined a small body of water that was used to protect small, shallow-draft ships. The Town Dock, located just north of Faneuil Hall, eventually was enclosed and filled in. So, neither kind of dock exists there.

Water Street:

This one remains correct as it stands. Water Street got its name not because it has water on it but because it went down to the water. Originally, however, Water Street extended from Spring Lane, which did have water on it—and very important water indeed. The Great Spring drew the Puritans here from their first landing in Charlestown, where the water was unfortunately brackish.

Water Street now ends a few blocks shy of the water and the city has boarded up the Great Spring. I find this unfortunate. Many European cities have fountains that gush pure drinkable water. Why should Boston hide clean water and obscure the existence of something so important to the city’s history?

Perhaps the reason lies in the shape, because Spring Lane is now a narrow pedestrian alley that runs from Washington Street to Devonshire Street with the Winthrop Building on one side and an office building on the other. That leaves little room for a fountain. Busy pedestrians pay little attention to the plaque on the wall that marks the spot.

Pragmatic Street Names

In general, the Puritans gave their streets functional, pragmatic names: Spring Lane held the Great Spring, School Street had the public school, British troops marched to the Battery on Batterymarch Street. They had little use for secular poetry and none at all for the dukes of England.

In general, the Puritans gave their streets functional, pragmatic names: Spring Lane held the Great Spring, School Street had the public school, British troops marched to the Battery on Batterymarch Street. They had little use for secular poetry and none at all for the dukes of England.

Yet it helps to know a little history so you can put memes like the one above in context. The author may have wanted to poke fun at Boston but, while the city may be quirky, the real reason for the disconnect lies in its age. Things change over centuries. You have to keep up without forgetting what came before.