When I said that I would write about Milk Street and Water Street, I assumed that both of Boston’s oldest byways would have long and complex pasts. Last week’s post about Milk Street confirmed that opinion. It took me hours to research, organize and write about a long street with a long history.

Short But Old

It turns out, however, that Water Street doesn’t have the same claims to fame. It appears on original maps of the city and it was shorter than Milk Street. Starting from Washington Street (the section then called Cornhill),it went all the way down to the Blue Bell Tavern and—what else—the water.

The sources that usually give me a wealth of information about Boston’s streets and lanes fall curiously reticent when it comes to Water Street. They mention it mostly in passing, when discussing directions, people and events. Why? I don’t know; it’s a mystery.

Nevertheless, I persisted and learned a few interesting things.

Origin of Water Street

According to the Book of Possessions (a government survey of houses and lands), Water Street was originally a part of “Springate,” or Spring Lane. Agents of Stephen Winthrop laid it out in 1654 through Winthrop’s marsh “from Henry Bridgham’s house to Benjamin Ward’s wharf, as far as his land goeth, and the town grants the residue of the way through the marsh.”

It was sometimes called, “the back street leading to Peter Oliver’s Dock” and the Lesser Draw Bridge at Kilby Street over the dock’s mouth; also, the “highway towards the spring.” In 1660-61, a lane cut through the estate of Elder Thomas Oliver, which was separated from the governor only by the spring, and connected it to Washington Street. It was all called Water Street in 1708.

Oliver’s Dock

In 1656, the town sold land on Water Street below Kilby Street to James Johnson. He deeded part of that plot to Peter Oliver in 1660-61. This section is included in Liberty Square.

In 1656-57, Peter Oliver bought marsh land on the north side from Stephen Winthrop. In 1809, the town sold the water course, or Oliver’s Dock, which extended west of Kilby Street, to William Phillips.

NOTE: Oliver’s Dock was not what we think of a dock or wharf now as a structure where vessels load and unload. Before the 20th Century, a dock was a small body of water in an enclosed basin or the slip between wharves. In the 17th Century, there were four of these on Boston’s waterfront: The Town Dock, Scottow’s Dock, and Atkinson’s Dock, which led to Oliver’s Dock. The latter was known as Oliver’s Dock because he owned most of the surrounding land.

Prominent Residents

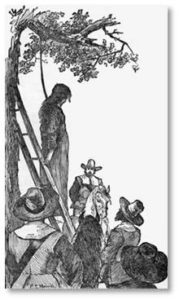

William Hibbens, a noted merchant and agent of the colony in England, lived on the south side just east of Devonshire Street. He died in 1654 and the following year saw his widow, Ann Hibbens, condemned for witchcraft and executed on the Great Elm. She had the unfortunate combination of being “quarrelsome and odious” as well as “having more wit than some.” There was nothing more dangerous than a smart outspoken woman who doesn’t suffer fools gladly — or keep quiet about it.

Next to this estate stretched the estate of Henry Bridgham, which extended to Milk Street. After James Dalton purchased the land, Congress Street extended through it.

In 1736, a tanyard owned by George and Robert Harris advertised on Water Street at the sign of the Tanner and Curriers and Oxhead. The following year they changed the name to the Boys and Bullocks Head.

The printer Thomas Fleet purchased the house on the north corner in 1744. He married Elizabeth Vergoose, who has been attributed with the collection of old rhymes and songs that gave her the name “Mother Goose.”

The Fire of 1760

Many buildings on Water Street burned in the fire of March 20, 1760. The fire began at the house of Mrs. Mary Jackson, who kept the Brazen Head Tavern on the east side of Washington Street and spread to Water Street as far as Oliver’s Dock.

It also burned structures on Devonshire Street, Congress Street, and Milk Street but was stopped at State Street.

The fire destroyed 349 buildings—174 houses and 175 warehouses, shops and other buildings—as well as several ships in port. The conflagration left over 1,000 people homeless. No one died, however, and only a few people were injured. This destruction gave the town the opportunity to straighten and widen some of its streets.

The parcel on which the Blue Anchor Tavern had stood near Oliver’s Dock, before it burned was sold the same year.

Boston’s Moving Pictures

A curious note records that In March of 1714-15, the artist Nehemiah Partridge advertised:

“…the Indian Mitchean or Moving Picture, wherein are to be seen windmills and watermills moving around ship sailing on the sea, etc., at his house in Water Street at the head of Oliver’s Dock.”

Did this mark the beginning of Boston’s appearance in the movies 258 years before The Friends of Eddie Coyle? Who knows? It’s difficult to imagine the technology he used, though.

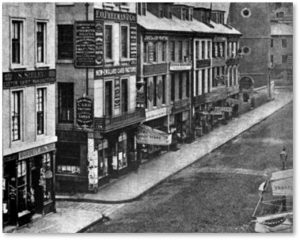

The part of Water Street from Devonshire to Oliver, burned again in the Great Fire of 1872. It now goes through Boston’s Financial District, a section of the city that was built up after that disaster.

Today Water Street runs parallel to part of Milk Street and ends at Broad Street, a couple of blocks shy of the Rose Kennedy Greenway. The harbor is further away now than it used to be, so Water Street no longer reaches the water.