In my previous post on the Cost of War, I dealt with the question of why we fight wars. This post concerns who fights war.

New York Times Columnist Maureen Dowd recently wrote a piece called “Manning Up, Letting Us Down,” that connects war to “hyper-masculinity.” She defines this as “fake tough-guy stuff, a caricature of strength.” In her column, Ms. Dowd recounts asking a fellow reporter, about the macho fever to invade other countries. He shrugged and said, “Men love war.”

Why? A good explanation comes from William Broyles, Jr. in Esquire. His article, “Why Men Love War,” offers an inside look at the many reasons why war is, for men, . “War is a brutal, deadly game, but a game, the best there is,” he says. “And men love games.”

You know who doesn’t love war?

Women.

War and Collateral Damage

Why? Because we are the collateral damage, the people who suffer and die when men play their deadly games. We know that war challenges our survival and that of our children, our homes, our communities. Rather than a game of dominance and destruction, it threatens to wipe out everything we hold dear.

We know the cost of children: months of carrying them in our bodies, pushing them out in pain and blood, feeding them with our own bodies. Home and communities keep us and our children safe. War turns us into victims and refugees.

Men’s Business and Collateral Damage

I’m reading a novel called “The Paris Apartment” by Kelly Bowen in which a male WWII spy says, “War is men’s business.” Yes, for the most part it is. Yet, men’s business has a way of spilling over onto others around them.

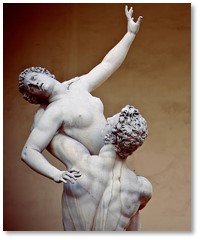

Pillage has always been a perk for the victorious warrior. So has rape. Fun for the man; not so good for the women. Between wars we gloss over the impact on non-combatants. We consign stories such as the “Rape of the Sabine Women” to history, a story from long ago. We look at artistic representations of that theme without considering what the Sabine women must have felt like.

Contemporary Offenses in War

Not, mind you, that wartime rape only happened centuries ago. I remember reading an account of a woman who was raped and impregnated during the Bosnian-Serbian war. She gave birth to the child in a barn, then stepped over it, left it in the hay, and walked out the door. The man (or men) responsible was, of course, long gone.

During wars, men have been known to skewer babies on bayonets, smash their heads against the wall, burn them with napalm, and bury them alive in mass graves. So, war isn’t very good for children either, even male ones.

In the 20th century, war devolved from considering women’s bodies as legitimate spoils to treating them as the field of battle. African warlords learned that a man would not take back a wife who had been raped. With a goal of destroying the social fabric, they raped women systematically and cut their thighs with machetes to mark them as soiled.

It represented a new and more debased level of warfare in which men fought not other warriors but women, who suffered rape and rejection. Men turned women into both the spoils and the spoiled.

Power and Opportunity

Now, I can hear male readers protesting that women are just as violent as men. That queens and empresses have waged war as well. Does that mean fewer women have fought wars only because we have had less power and opportunity to do so?

-

Catherine the Great fought the Turks and the Persians (they started it) but her real goal was to rationalize and reform administration of the Russian Empire. Historians consider her reign a golden age for Russia.

- The Empress Wu fought wars on the Korean Peninsula but during her 40-year reign, China grew larger, corruption in the court was reduced, its culture and economy were revitalized, and it was recognized as a great world power.

- Queen Elizabeth 1 fought three wars (one with Spain [they started it] and two with Ireland) but was religiously conservative compared to her father and half-sister. During her 44-year reign, English drama and seafaring prowess flourished. Queen Elizabeth 1 provided welcome stability for the kingdom and helped forge a sense of national identity.

- Pharaoh Hatshepsut probably fought a short war with Nubia but historians recognize her reign as a peaceful one based on trade.

I could go on, adding a few other female rulers, such as Cleopatra, but history simply does not provide enough female rulers to answer the question definitively. For every Margaret Thatcher there are thousands of kings, emperors, warlords, popes, princes, generals, presidents, and prime ministers who have waged bloody wars.

Comtesse de la Roche Guyon

I remember, however, visiting a chateau in France that also throws some historical light on how women govern. The Chateau de la Roche-Guyon rises on the banks of the Seine in two parts. The 12th-century medieval keep commands the hilltop. A troglodyte lower mansion is carved both from and into the limestone cliff behind it. A tunnel through the rock connects the two by way of 276 steps. (Roche means rock in French.)

The chateau commands the river; a fascinating place with an equally fascinating history. Our tour guide told us that one of the noble ladies managed the estate herself after the death of her husband. NOTE: I don’t remember the woman’s name but I think it was Antoinette de Pons-Ribérac, comtesse de La Roche-Guyon and marquise de Guercheville (1560 – 1632).

The guide told us that, widowed, the Marquise did what she thought best and that meant caring for the estate and the people who lived there. I commented that she could do this because she didn’t have a husband to forbid her. The guide looked startled but agreed that this was so. The Marquise also didn’t have a husband to spend their fortune on war, armor, weapons, horses, mistresses, and gambling.

The Marquise made many improvements including building a fountain so the women of the village didn’t have to haul water back from a distant spring. It probably cost a fraction of what her husband might have spent on armor, a sword, and a warhorse.

Thus, the estate prospered in a time of peace.

Imagine if Women Ran Things

Modern society has provided men with a few substitute venues for competing with other men to prove themselves, gain status, accrue power, and make money. Sports, at different levels, is one of them. Politics is another. You see this behavior in law firms and investment banks, albeit in a less physical way.

Perhaps, however, we need more women in charge of this world.

Imagine what Afghanistan might look like if women ran the country instead of a succession of warlords and, now, the Taliban. Would women and children be starving in Yemen without the intervention of Saudi men? Could Northern Ireland have avoided decades of bloody violence if the women had not been divided into hostile camps by their warring menfolk? Would Hutu and Tutsi women have hacked off one another’s limbs with machetes?

Follow the First Nations

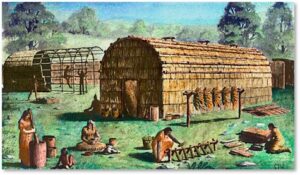

We could adopt the same approach some First Nations tribes took: the women owned the longhouses where a man could stay if the women agreed to give him hearth space. The men frequently left either to hunt or to fight. Fighting took place far from the longhouses, away from the women and children.

If we could keep war from becoming men’s business, we would have less fighting, fewer casualties, more living children, increasingly prosperous societies and greater achievements. Is that too much to ask?