Monday Author: Susanne Skinner

Cucina Provera means poor kitchen; but the style of food preparation and cooking is often referred to as food of the poor. Its origin is Italian, but the culinary influence extends into Austria. I grew up without knowing any of this but enjoyed many a cucina povera meal at my grandmother’s table.

The maternal side of my family hails from Tyrol, a 10,000 square foot province in the Austrian Alps. At the conclusion of World War I, the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye ceded Tyrol to Italy.

The maternal side of my family hails from Tyrol, a 10,000 square foot province in the Austrian Alps. At the conclusion of World War I, the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye ceded Tyrol to Italy.

My great grandparents emigrated from Tyrol to Crystal Falls Michigan in 1891 and eventually settled in Hurley Wisconsin. My grandparents were first-generation U.S. residents. Their simple and delicious way of preparing food did not change when they came to America and has been passed down through four generations.

This is part of my culinary heritage.

Cucina Povera: A Style of Cooking

Cucina povera is a way of thinking and living as well as a style of cooking. Italians have a deep connection to the earth and grow much of what they eat. A second and equally important trait is their philosophy of using everything they have. Nothing is wasted or taken for granted.

There is a frugality associated with this style of cooking. It underscores the importance of what is at hand, from gardens, chicken coops, bodies of water, and even the forest. The methodology behind this involves reusing and repurposing original ingredients into delicious leftovers or new dishes.

This legacy is thought to have originated with Italy’s rural poor, but it can be argued that it is simply a reflection of the food they had access to along with their commitment to making the most of everything.

My great grandparents were both frugal and creative. They had very little in terms of material possessions and sought a better life. It is the reason they emigrated, bringing their culture, values and traditions with them. Their recipes remain some of the most delicious food I’ve tasted and prepared.

Continuing the Traditions

I grew up eating many of these dishes although I never learned to make them. My grandmother’s and mother’s handwritten recipe cards are now mine—none of them with measurements or directions. Most of them list ingredients with accompanying instructions to” mix well” and bake “until done.” Measurements are vague; “a good handful,” and” three turns around a large pan” are all I have to guide me.

Five years ago, two cousins and I decided to re-create these recipes, documenting them with specific amounts and directions. Each of us thought the other knew how to make them and were stunned to learn none of us did. All we had to guide us was remembered tastes and textures.

Five years ago, two cousins and I decided to re-create these recipes, documenting them with specific amounts and directions. Each of us thought the other knew how to make them and were stunned to learn none of us did. All we had to guide us was remembered tastes and textures.

By creating a family cookbook we are continuing their traditions.

Creating a Family Cookbook

Our journey begins by sharing our collective knowledge and recipe cards. No surprise—each of us has slightly different versions! Some basic assumptions are set forth as we list the dishes and assign them categories. We agree to use only the freshest organic ingredients and make everything from scratch. There were no preservatives, growth hormones or additives when these recipes were created.

We think back to what and how the dishes were prepared. If we know the actual recipe name, a Google search offers additional guidance on the specifics of each dish. We use only ingredients they would have used. We test each recipe—sometimes four or five times—until we agree “it tastes just like I remember it.”

One recipe in particular calls for day-old breadcrumbs. In order to be authentic, we made the bread (just as our Grandmother did), and after we enjoyed it with a meal we let it dry and made our own breadcrumbs.

Cousins are invited to be testers and tasters. After a final round of tweaking and adjusting, the approved recipe is added to the cookbook with a photograph of the finished dish.

Cucina Povera Recipes

The original recipes date to the late 1800s and include potatoes, vegetables, pasta and cuts of meat that would be otherwise discarded. Below are three of my favorites.

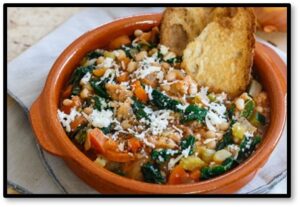

Ribollita (reboiled) means leftovers. This soup isn’t pretty but it’s delicious and even better reheated! It is traditionally thickened with day-old bread. This recipe closely resembles the final version of my Grandmother’s soup. It is at its finest when served with a crusty loaf of Tuscan bread. If you aren’t a bread baker, a store-bought loaf does nicely.

Ribollita (reboiled) means leftovers. This soup isn’t pretty but it’s delicious and even better reheated! It is traditionally thickened with day-old bread. This recipe closely resembles the final version of my Grandmother’s soup. It is at its finest when served with a crusty loaf of Tuscan bread. If you aren’t a bread baker, a store-bought loaf does nicely.

My Grandmother’s Canederli are legendary. All of us loved them, none of us learned to make them. Re-creating her recipe was a labor of love and this one was our guide. It is nothing more than stale bread dumplings, moistened with milk and bound with eggs. Her unique spin includes leftover salami or ham, fresh herbs and cheese. They are always served in homemade broth.

In the old country, families made their own ricotta. We tried it and couldn’t believe how easy and good it is! Sweet ricotta cream is a simple dessert on its own and makes a great topping. I learned to eat it with fruit, nuts and a drizzle of honey. There were no food processors back then so I suspect it was whipped by hand, and always light, creamy and delicious!

A Family Legacy

Ask any old-world Italian Grandmother, especially the older generations, if they prepare cucina povera and they will laugh. They lived through the great depression and post-war Italy and it is unlikely they even know the term.

Today the cucina povera style of cooking has been romanticized. In my Grandmother’s day it was simple food using fresh and hearty ingredients. It is always served from the heart to the table.