The business world focuses on two things: ways to make money and ways to save money. That’s how capitalism works. Ideally, you can do both but that doesn’t happen very often.

Just-in-Time Manufacturing

Back in the seventies, we imported the idea of just-in-time manufacturing from the Japanese. Should you be unfamiliar with the term, here’s a definition from “Inbound Logistics”

“Just in Time manufacturing (JIT) is a production strategy that produces goods based on customer orders. This strategy is used to minimize inventory and increase efficiency within a company’s supply chain. JIT closely coordinates the flow of materials, information, and equipment, so that customer orders are produced and delivered within specific time windows.”

This all sounds very good and the definition incorporates multiple business buzzwords. It doesn’t say, however, that Just-in-Time Manufacturing depends on the smooth, efficient, and timely shipment of materials around the globe.

This all sounds very good and the definition incorporates multiple business buzzwords. It doesn’t say, however, that Just-in-Time Manufacturing depends on the smooth, efficient, and timely shipment of materials around the globe.

Unfortunately, the globe sometimes has other ideas. It sometimes puts obstacles in the way of that smooth flow. These include unexpected events and human failures but they almost always inhibit shipments of goods and materials or close them down altogether.

The Trucks and the Bridge

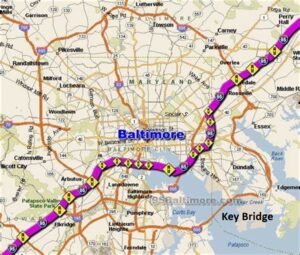

We are seeing one of these obstacles right now in Baltimore Harbor. When the cargo ship Dali lost power and destroyed the Francis Scott Key Bridge over the Patapsco River, it created a double shipping SNAFU. Trucks carrying goods and materials up the Route 95 corridor used the Key Bridge to take a straight route past Baltimore’s traffic.

We are seeing one of these obstacles right now in Baltimore Harbor. When the cargo ship Dali lost power and destroyed the Francis Scott Key Bridge over the Patapsco River, it created a double shipping SNAFU. Trucks carrying goods and materials up the Route 95 corridor used the Key Bridge to take a straight route past Baltimore’s traffic.

Now those trucks will have to either take Route 95 through the city itself or swing wide around it, adding miles and time to the trip. The supply chain will not improve until the bridge is rebuilt. That applies a whole new schedule to the concept of just-in-time.

The Ships and the Bridge

On the water, traffic in and out of the Port of Baltimore has come to a halt and will remain stopped until authorities:

- Lift the containers from the ship.

- Cut up and remove the crumpled pieces of bridge from the ship’s deck.

- Remove the ship from the channel.

- Find and remove the containers that fell from the ship’s deck to the river bottom.

- Find and remove all the pieces of the bridge now lying on the bottom.

Only when the river bottom is clean can maritime commerce resume. In the meantime, ships that were already in the harbor are trapped there and no new ships with their cargoes can enter. That shuts down the smooth, efficient flow of goods and materials completely. It also shuts down jobs and salaries for people who work in the Port of Baltimore.

Historical Supply Chain Snags

While I would hate to be the executive trying to explain why manufacturing has ground to a halt or customers won’t be getting their orders, the Dali accident is far from the only time this has happened. Consider these:

While I would hate to be the executive trying to explain why manufacturing has ground to a halt or customers won’t be getting their orders, the Dali accident is far from the only time this has happened. Consider these:

-

2010: The eruption of the Icelandic volcano Eyjafjallajökull ejected so much volcanic ash into the air, it closed air traffic for nine days. At the time, this was the largest air-traffic shut-down since World War II.

-

2021: The container ship EverGiven drifts aground and shuts down the Suez Canal shipping traffic for six days. This forces ships to either wait in an ever-growing backup or go around the Cape of Good Hope—a longer and more expensive trip.

-

2021: The Covid pandemic created such docking delays in the Port of Los Angeles that 86 container ships loitered offshore, unable to offload their cargoes. It created a Christmas backlog that affected millions.

-

2024: Beginning in 2023, Houthi rebels backed by Iran have attacked cargo ships and oil tankers approaching the Suez Canal through the Gulf of Aden. This situation continues and is forcing commercial traffic to avoid the Suez Canal and go around the Cape of Good Hope.

The Supply Chain at Home

All in all, it makes me believe that the supply-chain improvements that supposedly come with global shipping have too many problems for just-in-time reliability. It makes the old tried-and-true method of keeping an inventory of the parts and materials you need look more attractive. After all, a part on hand is worth two that can’t get there by the deadline.

And another thing: offshoring your manufacturing only works if the completed product—or even essential parts—can be shipped to where they will be assembled or distributed at less cost than doing so right here at home.

Shipping snafus, whether in the air, on the water, or by rail, increase costs. When that happens, your profits go right out the window.

At what point does offshoring manufacturing or assembly cease to make sense? At what point does the cost of moving goods around the world cancel out the savings from using underpaid workers in third-world countries?

A chain is only as strong as its weakest link. What does it cost when the supply chain breaks.

Will we ever find out?