The City of Boston tries to work with private developers to create public spaces in the projects that they build. This is part of a long tradition, called linkage grants, that enable the Boston to issue private money-making opportunities in return for public amenities without spending any public money.

Linkage Grants

That sounds like a good idea and it sometimes works well. Other times, not so great. Two examples from the past are the mills that were built on the Mill Pond and the permission given to Uriah Cotting’s Boston and Roxbury Mill Corporation to create water-powered mills in the Back Bay.

In both cases, the tidal power proved insufficient, the corporations didn’t prosper, and the projects fell into disrepair. Both the Mill Pond and the Back Bay were subsequently filled in to create new land for the city.

Approving Things Case by Case

Today the city attempts to leverage the current building boom to get new parks, winter gardens, pedestrian malls and other amenities at private expense. But they’re doing it on a case-by-case, lot-by-lot basis without a master plan.

Projects that work usually succeed because there is a plan, a design, guidelines and regulations, or an overall approach that imposes order and prevents visual chaos. This keeps developers from creating tiny little parks that are so small, so shady, and so overwhelmed by surrounding structures that they get little use. It also avoids the development of retail malls that are technically public spaces but function as shopping areas from which the developer gets rental revenues.

Jumping Over Hurdles

Without plans we also get public spaces that the public doesn’t know exist and never use because you have to jump over hurdles to get to them. I have written about a couple of these in previous posts, with directions on how to gain access:

Tim Logan of the Boston Globe also wrote about some of these “restricted use” public spaces in “Boston Pushes Developers to Create Better Public Spaces.”

Getting to Not-So-Public Spaces

To use spaces like independence Wharf or the Custom House Tower (now a Marriott Vacation Club property), you have to know:

- That the public space exists and is accessible. That can be difficult when it isn’t advertised or information is limited to one small sign tucked in an out-of-the-way location.

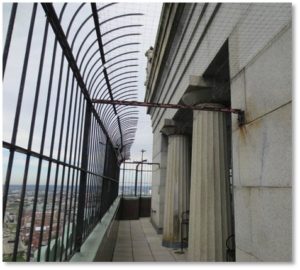

- When the public space is open and available. In the case of the Custom House Tower, for example, public access is limited to one tour at 2 pm on weekdays.

- How to get to it. Typically, one has to ask the right person in the right place and then get escorted to the elevator or up to the “public” space with a company chaperone. It doesn’t actually feel comfortable or relaxing. It took me two tries at the Boston Harbor Hotel to get the right person at the right time to take me up in the right elevator. My escort stayed with me while I looked around and then took me back down to the street again. This doesn’t feel welcoming and it discourages lingering or relaxing.

-

What you’re going to do when you get there. The building owners don’t provide much in the way of benches, tables or other amenities to make the space visitor-friendly.

Strolling around the narrow pathway across the gravel roof at Independence Wharf gets you great views of the city but then you’re done. The only place to linger is a glass-walled room—arguably good for bad weather but otherwise not all that welcoming. At least Marriott lets you walk around the Custom House Observatory supervised only by the peregrine falcons nesting above you.

Pacifying the City

Why do building owner make these spaces so difficult to reach and use? Because they don’t actually want the public to be there. Developers created the spaces to pacify the city and meet the regulations that allowed them to build on the sites. But, really, they would much rather have no one without a business reason to be in the building. You only have to visit one of these “public spaces” to feel how unwelcome you really are.

Mr. Logan quotes Kathy Abbot, Director of Boston Harbor Now:

“You’re creating a situation where you’re asking a business to provide a service that’s not quite what they do,” she said. “It’s inherently challenging.”

Avoiding the Public

Right. They don’t want to deal with the public’s intrusion, trash, questions or the security issues that come with allowing just anyone onto the roof, cupola, rotunda or lobby of their building. That maintenance costs money that comes from the bottom line and the less of it they have to spend on non-business requirements they better off they are.

Of course, a lot of these problems would not arise if they planned the public space better so that it could actually be used instead of making it an afterthought.that just barely meets the requirements.

The linkage grant creates a fundamental dichotomy between public use and private profit that has not served either one well. It’s wishful thinking on the part of the city and passive resistance on the part of the owners.

Public Space in the Back Bay

When the Back Bay was developed, it was through a tripartite partnership of the City of Boston, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and the Boston Water Power Company. The plan was designed by Arthur D Gilman and the state gave up 43% percent of its land—lots that could have generated revenue—to streets and parks. Goals of spaciousness, homogeneity, and ornamentation covered the entire area.

(You will learn all about this — and a lot more — on Boston By Foot’s

excellent Back Bay Tour.)

This is the kind of approach Boston needs to take now, instead of approving the grudging efforts of individual developers here and there on a onesy-twosy basis. This takes vision, planning, attention to nitty-gritty detail, and perseverance. Above all, it takes the courage to stand up to developers and make demands without fearing that they’ll pick up their ball and go home.

Are We Boston Strong?

Does the City of Boston possess those attributes? Not for a very long time. Years of small thinking and scrabbling for public money have left city authorities poorly equipped to do make demands and stick to them. A mentality of “getting by,” “making do,” and “taking what we can get” are what have led us to balancing shadows on the Common and the Public Garden with all that lovely, lovely money.

Let’s stop arguing and get real about telling developers what they can and can’t do in the city where — let’s face it — they want to make big bucks. Then we’ll really be Boston Strong.