“From the Halls of Montezuma to the shores of Tripoli . . .”

What does the Marine Hymn have to do with a street on Beacon Hill? And what American served as a spy for two presidents?

What does the Marine Hymn have to do with a street on Beacon Hill? And what American served as a spy for two presidents?

His name was William Eaton and Derne Street was named for the famous battle commemorated in the Marine Hymn. Derne Street keeps company with more famous Boston names like Revere, Hancock, Bowdoin, Irving, and Joy. But few people today knew who William Eaton was or how he helped the Marines won the Battle of Derna.

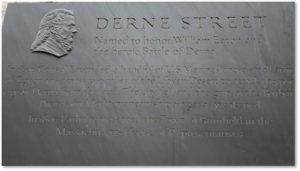

A Short Street and a Black Plaque

Derne Street runs just a short distance east to west, from Bowdoin Street to Hancock Street right behind the Massachusetts State House. Myriad people cross it every day, from government employees and law school students to tourists and residents of Beacon Hill. If any happen to look up onto the north wall of Ashburton Park, they will see a large rectangular plaque in black marble with a bas-relief profile of William Eaton and the following description of his deed.

Named to honor William Eaton and the heroic

Battle of Derna.In 1805 Consul Eaton led a handful of U.S. Marines and a small army of Egyptians across 500 miles of the Libyan Desert to attack tie port city of Derna from the land. The city fell and the grip of the Barbary Pirates on Mediterranean shipping was weakened.

In 1807 Eaton represented the Town of Brimfield in the Massachusetts House of Representatives.

William Eaton: Connecticut Farm Boy

Born in 1764, Mr. Eaton grew up on a Connecticut farm. In search of more adventure than could be found between rows of New England corn, he enlisted in the Continental Army at 15. After spending three unadventurous years as a clerk, he worked his way through Dartmouth College. Upon graduation in 1790, he took a job as a clerk in the Vermont House of Delegates.

He moved on to a career in politics but soon grew bored and returned to the army. His service included a tour under Major General (Mad) Anthony” Wayne and service as an “Indian fighter” in Ohio and Georgia. Captain Eaton’s record was tarnished, however, by a court martial for selling government supplies to the Creek Indians and using his time in the military to profit from private land deals. A review board reversed the conviction but Captain Eaton, his career tainted, resigned his commission in 1796 and moved to Philadelphia.

A Career in Espionage

There, Secretary of State William Pickering recruited Capt. Eaton into a small counter-espionage unit charged with surveillance on British and French spies inside the United States. Success as an undercover agent brought him to the attention of newly elected President John Adams, who assigned him to infiltrate a Spanish spy ring. (Why has no one made a movie about this man? Really.)

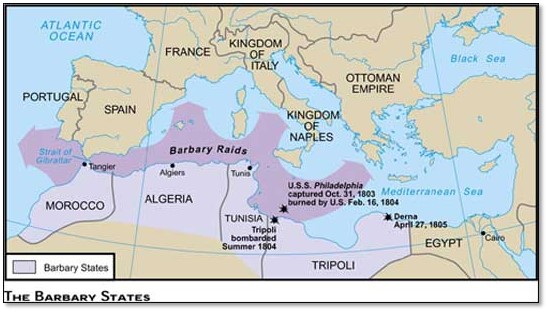

Offered a choice of diplomatic postings as a reward, he asked to become Consul to Tunis, a small, undeveloped and unimportant country on the northern coast of Africa. One of the four Barbary states, along with Tripoli, Morocco and Algiers, Tunis was ruled by the Ottoman Empire. Together the four states used organized piracy to dominate the Mediterranean Sea.

Offered a choice of diplomatic postings as a reward, he asked to become Consul to Tunis, a small, undeveloped and unimportant country on the northern coast of Africa. One of the four Barbary states, along with Tripoli, Morocco and Algiers, Tunis was ruled by the Ottoman Empire. Together the four states used organized piracy to dominate the Mediterranean Sea.

A man of volatile temper, given to violent outbursts and erratic moods, Consul Eaton also had a knack for using his office to enrich himself. He seems an unlikely choice for a diplomat representing the United States in a hostile part of the world.

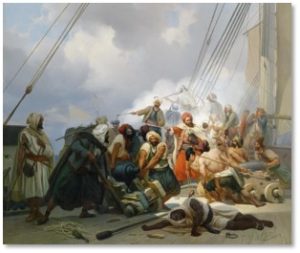

The Barbary Pirates

The Barbary Pirates had been attacking shipping in the Med since the 8th century, preying on the countries that bordered the sea but also going north to Ireland, Scotland, the west coast of England and even as far as Iceland. The pirates captured crews and passengers to sell in the Arab slave markets of North Africa. Men became galley slaves or laborers; women were sold as concubines. The pirates would also allow countries to ransom the slaves—a profitable endeavor—and sell back to them the cargo they had seized. The pirate states made even more by selling “rights of passage” that were simply “protection” money and a way to bypass Tunisian customs.

Consul Eaton had—again—a checkered career in Tunis but in 1800 James Cathcart, the American consul in Tripoli, requested his assistance. Mr. Eaton traveled to Tripoli, where he saw evidence of increased hostility. On May 14 of 1801, Yusuf Bey sent his men to attack the U.S. Consulate in Tripoli where they chopped down the American flag, thus declaring war on the United States.

Thrown Out of Tunisia

President Thomas Jefferson, acting without consulting Congress, sent a squadron of ships, which carried a complement of men from the three-year-old Marine Corps. They began a series of time-consuming but ineffectual skirmishes with the bey’s ships. Consul Eaton’s career as a diplomat ended in March of 1803 when the bey threw Eaton out of Tunis.

Mr. Eaton returned to the Med the following year as United States Naval Agent on the Barbary Coast, along with 1,000 rifles and $40,000 (over $663,000 today) from President Jefferson. He was also, however, a budding Islamist who later became fluent in Arabic.

Now I will fast forward through a lot of detail, some savory and some not.

You can read the whole story — and it’s worth reading — in the Warfare History Network.

The Battle for Derna

Mr. Eaton, now styling himself a general, led a rag-tag force from of 40 Marines, commanded by young First Lieutenant Presley O’Bannon, along with Turkish, Greek, French, English, Spanish, Indian, and Eastern European mercenaries on a cross-desert march of 500 miles from Alexandria, Egypt, to Tripoli. He picked up other fighters, including 20 more Marines, along the way until his “army” grew to over 1,000 people, not all of them fighting men.

On April 26, 1805, this group took up position outside Derna. The battle took place the next day and included an audacious charge by “General” Eaton’s troops against Mustafa Bey and the pirate stronghold’s defenders. Although outnumbered by 10 to 1, they prevailed and raised the United States flag over Derna—the first time in America’s history that the Stars and Stripes had flown over foreign territory.

More fighting ensued for weeks as the Americans fought to hold Derna. Unremarked by history or stirring martial hymns, however, was the conclusion. American State Department emissary Tobias Lear signed a peace treaty with Yusuf Bey and the Jefferson Administration ordered General Eaton to evacuate Derna. He refused to do so, knowing the garrison would be slaughtered after he left. When the U.S naval vessel Constellation arrived, however, he was forced to leave and was rowed out to the ship at night.

Derne Street: From Tripoli to Beacon Hill

From the shores of Tripoli to Beacon Hill, Derne Street reminds of an unusual man and a now-forgotten battle, if not its ignominious end. The Battle of Derna was a “decisive action” in the First Barbary War (1801 – 1805) and the first land battle waged on foreign soil after the Revolutionary War.

BTW: The 1950 movie, Tripoli, shows how, “ In 1805, the United States battles the pirates of Tripoli as the Marines fight to raise the American flag.” And he was played by Lance J. Holt in the 2004 movie, The Battle of Tripoli. But I think the dynamic, controversial, and mercurial William Eaton deserves a film of his own.