The Puritans who settled Boston in 1630 did not include gourmet cooking among their many strengths. They worked with a limited set of ingredients, of course—those which was grown regionally or could be imported at a reasonable cost.

Their cupboards didn’t contain zaatar, sambal oelek, or buffalo mozzarella. Recipes (receipts) tended to be simple, which is to say bare or basic rather than easy to prepare.

Boston’s Streets and Food

In addition, they equated fine food with European snobbery. The Puritans looked askance at creature comforts and even found staying warm in meeting house during the interminable Sunday sermons as luxurious. As Ellen Brown says in Cooking with the New American Chefs, “Food was viewed as the fuel to power our bodies.”

Nevertheless, everyone has to eat. That means some of Boston’s streets took the names of foodstuffs important to the city. A few of those streets have survived and are still extant. Most disappeared over years of changing neighborhoods, land making, population growth, and urban renewal. They often sported multiple, complicated names that depended on who wrote the deeds or the town clerk’s fancy and those names also changed over time.

A lists of Boston’s streets notable for their relationship to food: seafood, grain and milling, etc. appears below.

Seafood Streets

As a seaport, Boston had a long and important connection to Boston Harbor and the ocean beyond. Food that came from the sea formed a big part of what Boston’s citizens ate. This kept them strong and healthy, as both fish and shellfish are low in calories and cholesterol. Although the city never had a Cod Street, Clam Alley, or Lobster Lane, Boston’s streets did include:

As a seaport, Boston had a long and important connection to Boston Harbor and the ocean beyond. Food that came from the sea formed a big part of what Boston’s citizens ate. This kept them strong and healthy, as both fish and shellfish are low in calories and cholesterol. Although the city never had a Cod Street, Clam Alley, or Lobster Lane, Boston’s streets did include:

Fish Street: In 1789, today’s North Street had three names: (1) Ann Street from the Conduit in Union Street to the lower end of Cross Street; (2) Fish Street from Cross Street to the Sign of the Swan by Scarletts Wharf. Previously, it had gone by the names “common way by the water side, “street from the sign of the Red Lyon to Halsey’s Wharf,” and “the fore street from the great drawbridge towards the North Church,” “street leading ward the North Coffee House,” and “highway to Ship Tavern.” (3) The third segment, from Scarletts Wharf to the Battery, went by Ship Street.

Fish Street held a tavern that also had various names: Ship Tavern, Schooner Tavern, Sign of the Schooner, and The Schooner in Distress. The city consolidated all of these long and confusing street names into North Street in 1854 and Fish Street no longer exists.

Crab and Mackerel

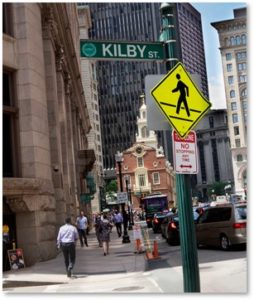

Today’s Kilby Street was formerly known as Mackerel (or Mackril) Lane, laid out in 1649. It ran close to the shore of Town Cove and had wharves extending from its water side.

Today’s Kilby Street was formerly known as Mackerel (or Mackril) Lane, laid out in 1649. It ran close to the shore of Town Cove and had wharves extending from its water side.

Mackerel Lane was very narrow until 1760, when it was widened and renamed Kilby Street. This honored Christopher Kilby, who was in New York when the Boston’s 1760 fire destroyed a large part of the city. He sent two hundred pounds to relieve the suffering of Boston’s residents.

Crab Lane: In 1673, a street ran from the house of Nathanial Bishop, known as the “Blew Bell” and then to the bridge. This street also had various names, including “highway from the drawbridge toward the South Battery,” and the “street from Swing Bridge to and by the Castle Tavern.”

In 1708, part of it became Battery March, and part Crab Lane. In 1805, the city extended Broad Street over part of Battery March, changing how it looks today. The Blue Bell Tavern occupied the southwest corner of Battery March and Crab Alley, standing on land that was originally a marsh.

Grain and Baking

Bread formed a staple of the Puritan diet, as it did in England. In the 17th Century, “corn” was the English name for wheat and what we now call corn went by the Indian name of maize. In the early years, wheat was in short supply while corn was plentiful and sometimes substituted for what the colonists could not get.

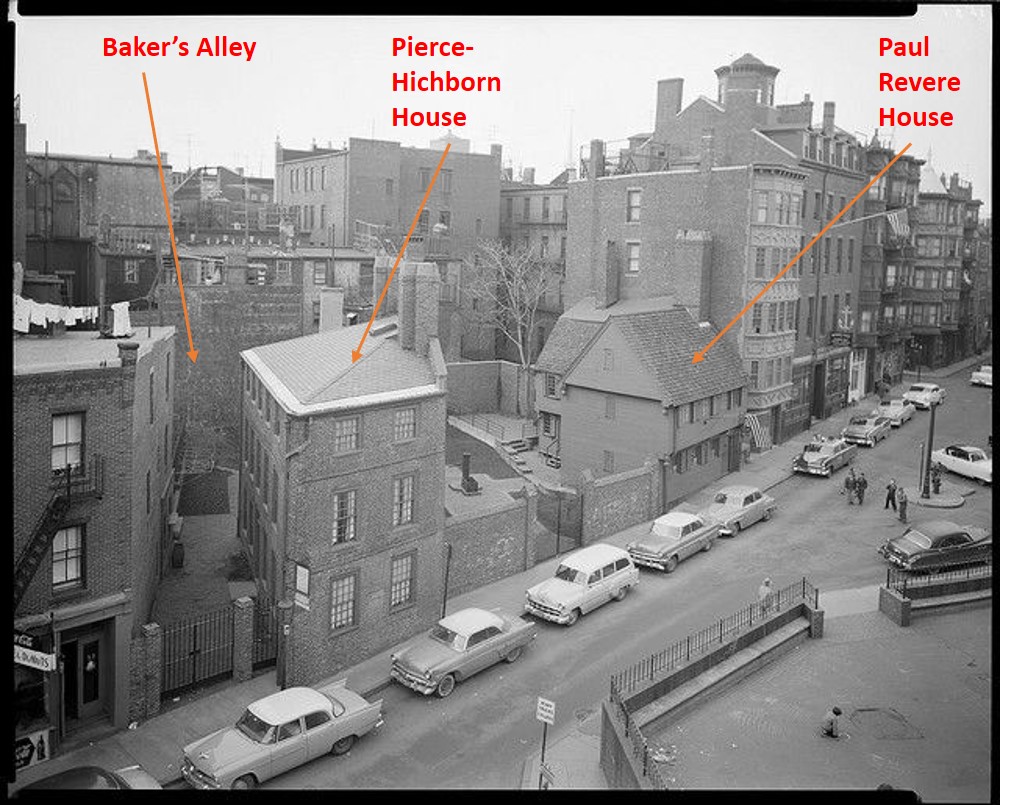

Baker’s Alley: In the North End, Baker’s Alley extended from North Square to the rear of the New Brick Church on Hanover Street. A remnant remains between the house of Moses Pierce-Hichborn, a boat-builder, and the Shaw House next door.

Another Bakers Alley existed on Fort Hill. (Presumably, Boston had more than one baker.) It, along with a Bread Street, were at the center of the 1849 cholera epidemic. Just the thought of bread and cholera together makes me queasy. Developers cut down Fort Hill in the mid-nineteenth century and the city used its clay soil to make the land underneath Atlantic Avenue. Thus, this Baker’s Alley and Bread Street ceased to exist.

Bread Street: The part of Franklin Street east of Devonshire Street was called Bread Street but the name was changed to Franklin Street in 1796.

Corn Court, in 1650 a lane from the dock, ran along the south side of Faneuil Hall. In 1670, records described it as “a wheelbarrow-way of full five feet” – impressive indeed. Corn Court, also known as “alley that leads from the house of James Oliver towards the dock,” became Corn Court in 1708. It incorporated Noyes Alley in 1796 and housed the Hancock Tavern, purchased by Morris Keefe in 1779. His daughter Mary married John Duggan, who was a noted lemon dealer. He advertised lemons for sale at the Sign of the Governor Hancock.

Dessert (Or Not)

Pudding Lane: What we now know as Devonshire Street led only from State Street to Spring Lane and had (of course) many names. It was called Pudding Lane from 1702 to 1766. At that time, city fathers renamed it to honor a merchant in Bristol, England, who donated £200 to “the sufferers.” This presumably refers to the fire of November 27 in the North End that destroyed the North Meeting House, Increase Mather’s house and many other residences around North Square.

Christopher Idone’s Glorious American Food tells us that pudding opened the meal and “Come at pudding time” was an invitation to dinner.

These puddings were based, on old English recipes but local cooks later added such specialties as Indian Pudding made with corn meal instead of scarce wheat. If you’ve never heard of Indian Pudding, I offer the recipe from the old Durgin-Park Restaurant, where it was a menu staple.

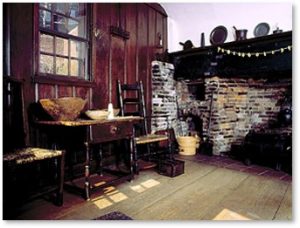

Cooking in the Kitchen

Kitchen Streets: With all that cooking going on, Boston’s streets would be remiss not to have a Kitchen Street among them. It started as a Beacon Hill alley running between Chestnut Street and Beacon Street that provided service access to the houses on either side. Kitchen Street later became Branch Street, which fits in with Beacon Hill’s other “tree streets.”

Even alleys can have notable residents, though, especially when they are on Beacon Hill. The Aga Khan lived at 66 Branch Street in a small converted coach house. One of the world’s richest men, he lived in Boston while studying at Harvard University from 1950-54, where he was an editor of The Harvard Lampoon.

Most of the streets listed above are no longer extant and none of the street names have survived. Boston’s streets may well include more lanes and alleys named after food and cooking. I can’t get to the library for additional research because of the pandemic, which limited my research. And the internet is, as we know, like a box of chocolates: you never know what your’e going to get. If you know of any additions, please let me know.

NOTE: This post should, by right, included Milk Street and Water Street. Because both of those thoroughfares are still extant and have long histories, however, they would take up too much room here. I will write about them separately.

What a great read – cooking and history!!

Good morning and thanks for posting this. Very interesting! My only question is about Mackerel Lane being widened in 1760 and renamed in honor of Kilby who was in New York at the time of the 1872 Great Fire…there must be a typo there somewhere. Looking forward to Milk and Water street entries and thanks again.

Good catch. It was the fire of 1760. I will amend the post. Thanks for flagging the mistake. I’m glad you enjoyed the post!