Unlike the “food and cooking streets” I detailed in last week’s post, Milk Street is still extant, still vibrant, and still important. It once housed several important historical residents and has not one, but two connections to food and cooking in Boston.

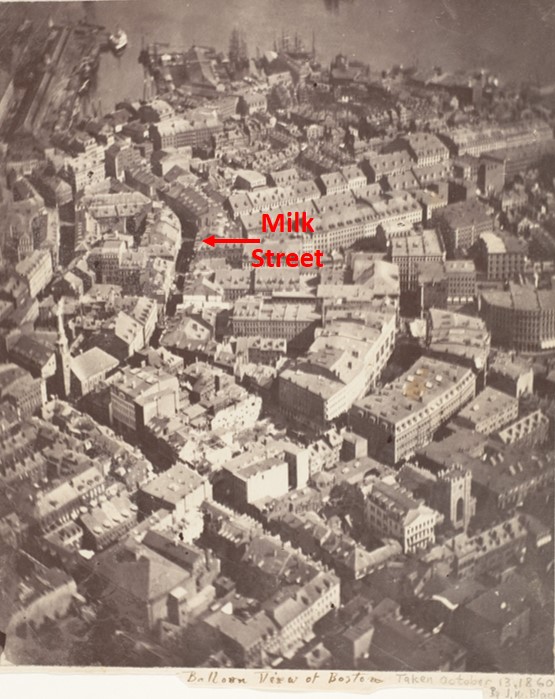

Milk Street begins at Washington Street with the Old South Meeting House on one corner and retail stores on the other. It curves through the Financial District, crosses the Rose Kennedy Greenway and ends at Central Wharf in front of the New England Aquarium. It dates back to the city’s earliest days and was part of the town’s important business section.

Milk Street began as a short street extending off Washington Street, that accumulated the usual collection of names: “Fort Street,” “the Front Street,” “lane from Robert Reynolds to the Marsh,” and “highway leading to the seaside.” In 1673, it was extended through the land of Benjamin Ward to the sea. It became “lane from the South Meeting House to Atkinson Dock” and “South Meeting House Lane,” until 1708 when it became Milk Street.

Naming Milk Street

How did it get its name? You can pick from two theories:

- It was named after a milk market at that location. Hmmm. In 1733, Boston voted to establish three markets: one in the vacant space near the town dock, one at the open space before the Old North Meeting House, and one near the great tree at the south end. None of these locations is near the corner of Milk and Washington Streets.

- In her 1952 work “History and Genealogy of the Milk-Milks Family,” author Grace Croft proposes that Milk Street may have been named for John Milk, an early shipwright in Boston. The land was originally conveyed to his father, also John Milk, in October of 1666.

Given Boston’s propensity for naming streets after prominent residents, the second option seems more likely to me. Although it may not have been named for actual milk, the street does have connections to food and cooking.

Benjamin Franklin

“A house is not a home unless it contains food

and fire for the mind as well as the body.” – Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin was born the 15th of 17 children in a house on Milk Street between Washington and Hawley Streets. The 1874 building that currently occupies this space identifies itself as “The birthplace of Franklin” on its cast-iron facade and has a bust of the great polymath in a Gothic niche above the second floor. He was baptized on the day of his birth in 1706 in the Old South Church nearly across the street on the corner of Washington. In his childhood he in presumably (I couldn’t resist) thrived on his mother’s milk

Benjamin Franklin was born the 15th of 17 children in a house on Milk Street between Washington and Hawley Streets. The 1874 building that currently occupies this space identifies itself as “The birthplace of Franklin” on its cast-iron facade and has a bust of the great polymath in a Gothic niche above the second floor. He was baptized on the day of his birth in 1706 in the Old South Church nearly across the street on the corner of Washington. In his childhood he in presumably (I couldn’t resist) thrived on his mother’s milk

Other Famous Residents

The home at 19 Milk Street was the residence in the 1600s of Katherine Gorham, the widow of John Stevenson who married Boston’s first settler, the Rev. William Blackstone. Governor William Endecott performed the ceremony, after which the newlyweds set out on Rev. Blackstone’s white ox for their new home in Rhode Island’s Blackstone Valley.

On the northeast corner of Milk Street and Federal Street lived Captain Thomas Cromwell, who sailed from Boston a common seaman and returned a rich man. He left six bells to the town.

America’s First Restaurateur

The northwest corner of Milk and Congress held the famous Julien Restorator, established in 1793 by French-born Jean Baptiste Gilbert Payplat dis Julien. This was the restorator’s second location, as M. Julien moved it from Congress Street in 1794.

This establishment is credited with being the first true restaurant in America, where customers came just to eat, as separate from taverns where travelers stayed as well as dined. It was certainly the first stand-alone restaurant in Boston and a novelty in the New World.

This establishment is credited with being the first true restaurant in America, where customers came just to eat, as separate from taverns where travelers stayed as well as dined. It was certainly the first stand-alone restaurant in Boston and a novelty in the New World.

M. Julien modeled his restorator on the restaurants of his native Paris, emphasizing the healthful aspects of the dishes he prepared, which were supposed to “restore” he good health of his customers. In an early marketing coup, he combined the words “restaurant” and “restore” to create his restorator.

On the Menu

Boston’s wealth elite flocked to the Julien Restorator, which offered:

“Excellent wines and cordials, good soups and broths, pastry in all its delicious variety, alamode beef, bacon, poultry, and generally, all other refreshing viands, will be kept in due preparation: and a bill of fare will be kept … from which each visitor may command whatever may best suit his appetite.”

Culinary historians credit M. Julien with introducing to America the julienne soup, a composition of vegetables in long, narrow strips. He died in 1804 and is buried in the Central Burying Ground. The restorator continued operation under his widow, Hannah, who sold it after 10 years to a Frederick Rouillard, who ran it until 1823. The building was demolished the following year.

M. Rouillard then moved further down Milk Street to employ his culinary skills at the Stackpole House on the east corner of Devonshire Street. There, he served breakfast in addition to dinner and supper.

The Post Office

Continuing our historical progress down Milk Street, we come to the corner of Milk and Devonshire Streets. Keep in mind that all the buildings along the south side of Milk Street for six blocks from Washington Street to Pearl Street were destroyed in the Great Fire of 1872,

One of the first post offices in Boston was located here in 1711, when the first regular postal routes to Maine, Plymouth and New York were established. The cornerstone of the Post Office was laid on the corner of Milk and Devonshire Streets, former site of the Stackpole House, and the corner was later included in the McCormack Federal Building.

Residence of Robert Treat Paine

The west corner of Federal and Milk Streets held the birthplace and residence of the lawyer, judge and statesman, Robert Treat Paine. He lived all his life in the two-story brick mansion that stood here, with back gardens that extended down Federal Street. Robert Treat Paine signed the Declaration of Independence just below John Hancock. He is one of the three signers interred in Old Granary Burying Ground.

Post Office Square

Milk Street goes through the part of Boston formerly known as the Old South End. It cuts across the narrow end of Post Office Square where a horse fountain designed by Peabody & Stearns 1912 honors George T. Angell, founder of the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

The Great Fire of 1872 devastated this area, destroying all the buildings but allowing for the later re-alignment of some streets and the creation of this square. The square’s beautiful Norman Leventhal Park designed by Halvorson Design Partnership, demonstrates a highly successful public/private partnership. The park is beautiful, functional, and well maintained—a green gem surrounded by large granite commercial buildings — all built after 1872.

The Langham Hotel (formerly the Meridien) on Pearl Street along the east side of Post Office Square, once held the French fine-dining restaurant called “Julien at Le Meridien” as well “Julien’s Bar and Lounge.” Both were named after Jean Baptiste Julien.

NOTE: The corner of Milk and Kilby Streets two blocks further down once held the first Jordan Marsh store at Number 129. Founded by a 29-year-old Eben Jordan, it opened in 1851 and was so successful, he opened a new store on Washington Street in 1861.

Milk Street and Multimedia Cooking

When we reach the triangular block bordered by Milk Street, India Street, and the Fitzgerald Surface Road along the Greenway, we come to the third culinary establishment. I discussed the Flour and Grain Exchange Building in a previous post. Today, I want to mention Christopher Kimball’s Milk Street, described as “a multimedia, instructional food preparation organization created by Christopher Kimball.”

Multimedia, indeed. Mr. Kimball’s organization comprises a magazine called Christopher Kimball’s Milk Street, a cooking school, Milk Street Radio, a website for video podcasts. as well as Milk Street Live! Which broadcasts live events. It offers global home cooking, “an invitation to the cooks of the world to sit at the same table.” Jean Baptiste Julien may have been right at home there.

I stumbled into it when I was researching the post on the building without knowing what it was. I didn’t have time to stay long but it smelled great in there.

The End of the Road

Milk Street crosses the Rose Kennedy Greenway and ends just before the New England Aquarium. It has crossed Boston’s earliest areas, fed Boston’s elite, housed famous men, survived the Great Fire of 1872, and embraced the Big Dig. We may not know how or why it was named but it certainly earned its place among Boston’s “food and cooking streets.”

Great history of Milk St.! I just stumbled upon it. Thanks!