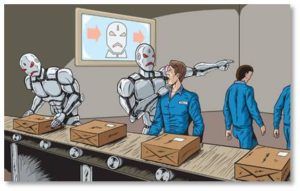

Back when I wrote posts ringing the alarm about what robots and automation would do to the American worker, I got the standard replies. They came from experts rephrasing common wisdom. They based their rebuttals on what happened when automation replaced 10 million agricultural workers with big machines.

Back when I wrote posts ringing the alarm about what robots and automation would do to the American worker, I got the standard replies. They came from experts rephrasing common wisdom. They based their rebuttals on what happened when automation replaced 10 million agricultural workers with big machines.

Don’t worry, people said:

- “Technology and automation will create more jobs than they replace. Sure, some workers will get the short end of the stick but they only have low-end jobs.”

- “The economy will boom and workers replaced by robots will have shiny, brand-new jobs to choose from.”

- “increasing productivity will make life better for everyone. Sure, there will be a period of adjustment and some people will take a hit, but things will improve in the long run.”

The automation trend has been underway for a while now, so how are things going? Well, the New York Times has issued a status report and they have given us an answer: Not so good.

A Work Force Divided by Automation

The NYT’s Eduardo Porter provides the big take-away right up in the title: “Tech is Splitting the U.S. Work Force in Two.” As in, the haves and the have nots; … the workers who matter and the ones who don’t … the people who can earn a living at their jobs and those who can’t. The economy is booming and jobs are growing but that high tide of growth and prosperity is not lifting all boats.

The NYT’s Eduardo Porter provides the big take-away right up in the title: “Tech is Splitting the U.S. Work Force in Two.” As in, the haves and the have nots; … the workers who matter and the ones who don’t … the people who can earn a living at their jobs and those who can’t. The economy is booming and jobs are growing but that high tide of growth and prosperity is not lifting all boats.

The NYT article should garner more attention than it probably will, given a news cycle that moves quickly from one disaster and political outrage to another. We don’t have much time for anything deeper or more serious than what’s trending—which is all the more reason to read this analysis.

Automation and Quantity vs. Quality

Should you lack the time to read the whole article and look at the helpful charts, I have pulled out my own highlights:

- Automation is changing the nature of work by driving workers without a college degree from well-paying job into dead-end service jobs with much lower wages.

- These less-educated workers fill positions that generate smaller profits per employees in companies that make money by keeping wages as low as possible.

- In low-wage jobs, employers lack a financial incentive to replace workers with robots because cheap humans are more cost-effective than expensive robots.

- Economists are beginning to worry that their assumptions could maybe, possibly, unthinkably, be wrong.

- It is possible to increase productivity and harm labor at the same time.

The landscape of work ahead may look more like the bifurcated land of Panem in The Hunger Games than the experts had predicted. And we know where that leads.

The landscape of work ahead may look more like the bifurcated land of Panem in The Hunger Games than the experts had predicted. And we know where that leads.

“But wait,” you argue. “The economy is booming the quarterly jobs reports show an ever-increasing quantity of jobs and a continuously decreasing unemployment rate.” What could be bad?

Ummm, well …

Solving the Economic Puzzles

All of this explains some of the conundrums that have been puzzling economists for months:

All of this explains some of the conundrums that have been puzzling economists for months:

- The sluggish growth of overall productivity.

- The numbingly slow increase in worker’s wages despite high corporate profits.

- The decline in the share of national income going into the paychecks of ordinary workers.

In the report, “Automation and New Tasks: The Implications of the Task content of Production for Labor Demand” by Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo, the authors conclude that,

“…in the case of automation, the displacement effect (the adverse shift in the task content of production) reduces the labor share in value added. Although value added increases, a smaller share of it accrues to labor. As a result, automation may reduce wages and employment when the productivity improvements it brings are small.”

In layman’s terms, automation screws employees by taking away their jobs and lowering their wages.

And Now for the Kickers

- Jobs have fallen in every industry that introduced technologies to improve productivity.

- Businesses are not even getting a big return on their investment in machines that replace human workers.

Mr. Porter quotes former Treasury Secretary and Presidential advisor Larry Summers, who says, “Until a few years ago, I didn’t think this was a very complicated subject. The Luddites were wrong and the believers in technology and technological progress were right.” He then adds, “I’m not so completely certain now.”

Theory vs. Practice

As Messrs. Acemoglu and Restrepo conclude;

“Our framework has clear implications for the future of work, too. Our evidence and conceptual approach support neither the claims that the end of human work is imminent nor the presumption that technological change will always and everywhere be favorable to labor. Rather, our approach suggests that if the origin of productivity growth in the future continues to be automation, the relative standing of labor, together with the task content of production, will decline. The creation of new tasks and other technologies raising the labor intensity of production and the labor share are vital for continued wage growth commensurate with productivity growth. Whether such technologies will be forthcoming depends not just on our innovation capabilities but also on the supply of different skills, demographic changes, labor market institutions, tax, and R&D policies of governments, market competition, corporate strategies, and the ecosystem of innovative clusters.”

Which leads me to my personal, oft-repeated stroke of wisdom. Robots and automation may just presage widespread joblessness because robots buy nothing.