The Niles Building on Boston’s School Street, sits at the center of the block in a neighborhood of historical buildings. It has a somewhat shadowed history of its own. This unassuming office and retail structure once stood in the middle of a 20th Century financial scandal.

The Two Niles Buildings

The current Niles Building actually replaces an older structure of the same name which, in turn, was built on the site of the home of John Warren, brother of Joseph Warren.

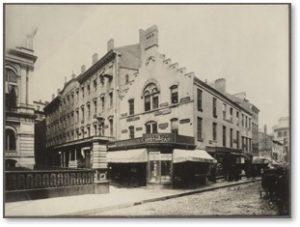

The first Niles Building stood on the corner of School Street and City Hall Avenue, backed up to a large commercial building called the Niles Block. Erected some time before 1880, this significantly smaller structure had only three floors and a stepped gable on the roofline at both ends.

J.P.T. Percival’s Pharmacy under the awnings on the building’s north end sold sodas for five cents apiece. A “Ladies and Gents Dining Room occupied the south corner.

In 1915, the second Niles Building at 27 School Street, designed by architect Charles Howard Walker, went up. This building has a brick first floor, a cast-iron façade on the second story and granite on the four floors above that.

The Securities Exchange Company

We’re concerned with the fifth floor, however. That’s where, in 1920, an Italian immigrant named Carlo Pietro Giovanni Guglielmo Tebaldo Ponzi, set up the office of his Securities Exchange Company.

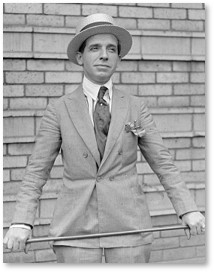

This short, slight man, known to history as Charles Ponzi, created one of the greatest frauds of the 20th century. His legacy lies in the term, “Ponzi Scheme,” a form of ongoing infamy.

The Ponzi Scheme

I don’t have room to go into the entire story, fascinating as it is, in this post. Suffice it to say that Charles Ponzi bilked the people of Boston, many his own countrymen, of between $15 and $20 million dollars in a few short months of 1920. That’s $187,052,571 to $249,403,428 in today’s money. Using the fraudulent arbitrage of International Postal Reply Coupons, he attracted investors of all kinds from all over.

Charles Ponzi did not discriminate, taking “investment” in amounts as small as $5 and accepting money from police officers and priests, alike. When the scheme blew up, there was a run on his offices. Mr. Ponzi bought donuts and coffee for the crowd and reassured them that they money was safe.

In the end, however, he returned only $8 million to his creditors, who received checks representing .5% of their claims. The complete story of Charles Ponzi’s massive fraud occupies whole books, such as:

- The Rise of Mr. Ponzi: Charles Ponzi by E. L. Kersten

- Ponzi’s Scheme: The Story of a True Financial Legend by Mitchell Zukoff

- Ponzi: The Incredible True Story of the King of Financial Cons by Donald Dunn

- The Rise of Mr. Ponzi: Charles Ponzi by Charles Ponzi

Managing the Crowds

The way a Ponzi Scheme works, as Bernie Madoff exploited 90 years later, is that the perpetrator pays initial investors with the money provided by subsequent investors. Money is shifted from one account to another without any actual trading taking place. Ultimately, Charles Ponzi’s Securities Exchange Company attracted some 40,000 investors.

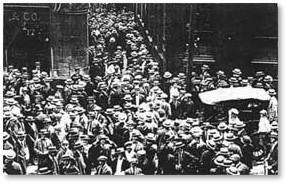

The get-rich-quick fraud drew crowds of such size that the Boston Police Department put mounted officers on School Street. The Proximity of Boston City Hall next door might have had something to do with the extra security. In his autobiography, Mr. Ponzi wrote:

“A huge line of investors, four abreast, stretched from the City Hall Annex, through City Hall Avenue and School Street, to the entrance of the Niles Building, up stairways, along the corridors…all the way to my office!”

When the old Boston Post newspaper exposed Charles Ponzi’s fraud, he had $4 million in assets, $7 million in liabilities and $61 in postal reply coupons.

The Niles Building Today

Charles Ponzi went to Federal prison on charges of mail fraud and state prison on other charges after that. His wife, Rose, took a job as bookkeeper at the Cocoanut Grove nightclub. She divorced him when he was extradited back to Italy at the end of his last prison term. He died in Brazil in 1949, alone and destitute. His name lives on in the scheme he invented and that was used again to great effect by Bernie Madoff.

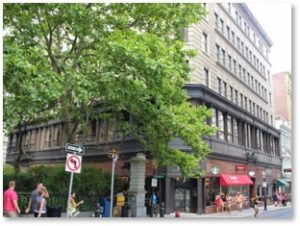

The crowds of office workers heading to lunch and tourists streaming along School Street from King’s Chapel to the Old South Meeting House have no idea that they have passed by the scene of an enormous financial crime.

Today the renovated Niles Building houses trendy shops and restaurants on the first floor. A medallion over the front door displays the date of its construction.

A Starbucks occupies the corner where J.P.T Percival’s Pharmacy once stood. A cup of coffee will cost you a lot more than five cents, though. I think Charles Ponzi would have found that a scheme after his own heart.

Read about Charles Ponzi’s Lexington house in this post from 2013.