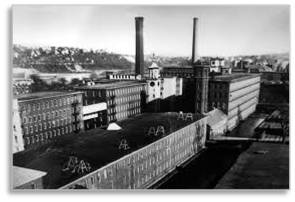

The 1800 @Lowell #textilemills were kept hot and humid to prevent the thread from breaking and to minimize the threat of explosion from cotton dust. Windows were nailed shut, even in the summer, to maintain these conditions, a primitive form of environmental control. The workers breathed in lint and smoke from the oil lamps all day and they were deafened by the noise.

The 1800 @Lowell #textilemills were kept hot and humid to prevent the thread from breaking and to minimize the threat of explosion from cotton dust. Windows were nailed shut, even in the summer, to maintain these conditions, a primitive form of environmental control. The workers breathed in lint and smoke from the oil lamps all day and they were deafened by the noise.“Instantly they were caught up in a Hellish noise so great, so overpowering, that human speech was impossible. Here they heard only the shrieking, pounding, thudding, clattering voices of the machines, and they were struck dumb by the cacophony, the maddening, mind-shattering din.” And they endured this for 12 hours a day, six days a week—with no headphones for protection.

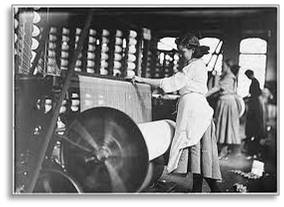

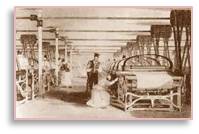

The machinery moved fast and relentlessly. Brass-tipped shuttles flew back and forth at great speed. There were no safety guards, and no nurse on duty. No one could have dreamed of OSHA.

Women wore long dresses, long sleeves, and long hair, yet to be careless was to court disaster. Catching a sleeve in the machinery meant losing a hand or an arm. A strand of hair, fallen out of its bun in the humidity and into the machinery could cost a woman her scalp. The women worked very carefully, holding their bodies well away from the moving parts as they reached in to fix a problem.  In February Hill, her novel of the textile mills in Fall River, Massachusetts, Victoria Lincoln described parents dosing their children with laudanum at bedtime so that they would sleep through the night. As horrified as we might be by the thought of giving small children daily narcotics, (the Victorians had no such qualms) we have to consider what their lives would become if a parent, sleep deprived and clumsy, lost and arm and became disabled. Were he fortunate enough to survive the injury, he would be thrown out of his job and his family would lose their mill housing. Company management would take no responsibility for his accident or the family’s wellbeing and the government had no programs to keep them from freezing or starving to death.

In February Hill, her novel of the textile mills in Fall River, Massachusetts, Victoria Lincoln described parents dosing their children with laudanum at bedtime so that they would sleep through the night. As horrified as we might be by the thought of giving small children daily narcotics, (the Victorians had no such qualms) we have to consider what their lives would become if a parent, sleep deprived and clumsy, lost and arm and became disabled. Were he fortunate enough to survive the injury, he would be thrown out of his job and his family would lose their mill housing. Company management would take no responsibility for his accident or the family’s wellbeing and the government had no programs to keep them from freezing or starving to death.

Exhausted operatives petitioned to shrink the work day to 10 hours and were labeled troublemakers. For an unmarried woman, however, the danger did not come from being discharged and losing one’s living. The real danger was that, “men would shun them, that no man would ask a trouble-maker—even one who worked in a good cause—to be his wife. That fate—spinsterhood—was too high a price to pay for even Ten Hours.” The irony is that these women were already spinsters in the word’s literal meaning, spinning thread every single day.

The mill owners never imagined that their loyal operatives would revolt. But, then, “They had not anticipated even their own greed, which would seduce them to drive their operatives to the point of death in order to maintain the companies’ profits.”

Call the Darkness Light opens a fascinating window into a world not so far in the past or so distant in miles from where I sit now. The Lowell Experiment kindled sparks for women’s rights and workmen’s rights. The proprietors could never have imagined that, either.