When I’m leading a walking tour for Boston By Foot, I like to take my guests down hidden passages and narrow alleys, places they would never find on their own, even with a guide book. Unlike European cities with their medieval lanes and overhanging buildings, however, Boston has only a few of these passageways.

I know of three: one each on Beacon Hill, in the North End and in the Bay Village. So, I was very interested to learn about an old passageway that had been built by a rich Bostonian for his own convenience.

This passageway also connects two posts about Boston’s Streets that appeared previously in The Next Phase Blog: Pearl Street and Winter Street.

Thomas Handasyd Perkins

Thomas Handasyd Perkins (December 15, 1764-January 11, 1854) was a wealthy Boston merchant. He partnered with his brother, James, to run a business in St. Domingue (now Haiti) that traded in slaves, flour, horses and dried fish. In 1785, the brothers expanded and enlarged their fortunes in the China Trade. Mr. Perkins contributed a great deal to the city of Boston as a philanthropist, as a prominent member of the Federalist Party, as a member of the Massachusetts legislature, and as a member of the local militia, which led to his title of Colonel.

His connections to American history are astonishing. He witnessed the Boston Massacre and at 12 heard the first reading of the Declaration of Independence from the balcony of what we now call the Old State House. He later became acquainted with George Washington.

A list of the important Boston institutions and commercial advances Thomas Handasyd Perkins invested in, supported, or funded would take more room than I have in this post. It would be interesting to draw a map that connects his residences to each. Those strings would stretch from the mills of Lowell to the Bunker Hill Monument in Charlestown.

When he moved from his mansion on Pearl Street to a new residence on Temple Place, Mr. Perkins offered the vacant house to what is now the Perkins School for the Blind. When in 1839 the school needed more room, he sold the building and gave them the money to purchase a hotel in South Boston.

The Perkins Tunnel to Winter Place

Col. Perkins’s new mansion faced south on Temple Place in what was then an upscale residential neighborhood just east of Boston Common. He built a large stable and pasture behind it on Winter Street on land once owned by Hezekiah Usher. To go easily from home to stable, he created a passageway that still exists.

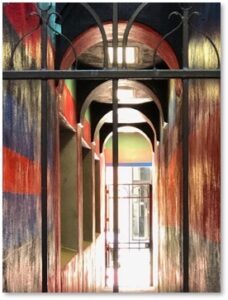

This brick tunnel runs from Temple Street to the end of Winter Place. Unfortunately, it has locked gates at either end and you cannot walk through, although you can see from one entrance to the other. I doubt the wealthy and conservative Mr. Perkins would recognize its current appearance, though.

Finding the Perkins Tunnel

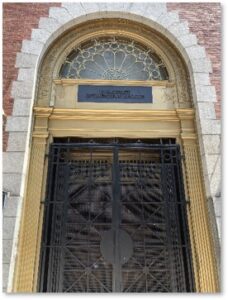

To reach the Perkins Tunnel, walk to the end of Winter Place and keep to the left. You can take a few steps down the brick-paved passageway before you come to an iron gate. A sternly worded sign to the right warns:

“No Trespassing,

Violators Subject to Arrest.

Police Take Notice.

No Trespassing.”

Watch your step, as the footing demonstrates what would happen if the tunnel remained open.

The tunnel has been painted in bright psychedelic stripes that give it the look of an amusement-park fun house. Lights between the arches of its ceiling keep it well illuminated. To reach the other end, you have to walk around the block, either on Tremont Street or Washington Street and then back along Temple Place.

The Temple Place end of the tunnel lies just to the southeast of Mr. Perkins’s second mansion, which is also still extant, although no longer a residence. Here, another locked gate blocks entry right at the sidewalk.

I don’t know the reason for the garish paint but I think a coat of solid white would improve the tunnel’s appearance.

The Perkins Mansion

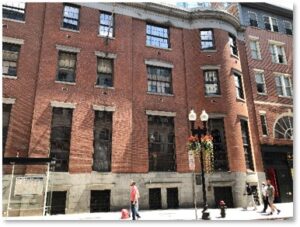

If you stand on the opposite side of Temple Place, you will see the Perkins Mansion to the left of the tunnel. Once, the large Doric portico of the entryway was bracketed by bow windows. The building still has the east bow window but the matching west bow is gone.

Thomas Handasyd Perkins lived here, visited by his married daughters and many friends who lived in similar elegant residences on Temple Place.

According to Caroline Curtis, his granddaughter, the heavy front door was live oak, “made of a piece of the old ship Constitution.” The door, alas, has disappeared.

The granite blocks on the home’s façade came from the Quincy quarry that supplied the stone for the Bunker Hill Monument. As one of his many investments, Col. Perkins encouraged the purchase of that quarry, and the development of the Granite Railway to move the blocks. It was one of the first horse-drawn railways in America.

Inside Col. Perkins’s Mansion

Ms. Curtis described the interior as having a

“…wide vestibule, with marble floor and on each side pedestals holding marble statues and steps leading up to a handsome circular hall.”

Twenty tree Italian marble fireplaces once warmed the home’s private rooms and reception areas.

Banking and the Law

The Provident Institution for Savings acquired the mansion in 1854 for $52,000—about $1,498,750 today. The Provident was formed in 1816 as America’s first mutual savings bank. The bank renovated the mansion with ornate vaults and a large marbled banking hall with Victorian brass ornamentation. Col. Perkins’s front drawing room, which became the bank president’s office, held one of the marble fireplaces

In 1991, the Massachusetts Continuing Legal Education bought the building. They turned the banking hall into a 350-seat auditorium and converted the mansion’s three floors into office and learning spaces. Fortunately, the organization retained and restored many of the original architectural details. These include much of the ornate plaster work and marble wainscoting.

I would have gone in but I was researching this in July when everything was closed. You can see photos of the interior on the Massachusetts Continuing Legal Education institution’s website but they don’t look much like a home, even a large and elegant one.

A Distinguished End

Thomas Handasyd Perkins was married to the former Sarah “Sally” Elliot for over 60 years and the couple had six children. When he died at 89, the state legislature adjourned so its members could attend the service in the Federal Street Church. Col. Perkins is buried in the family plot at Mount Auburn Cemetery where his grave is marked by an Italian marble sculpture of a dog carved by Horatio Greenough.

Despite his lack of concern for the morality of slave trading or of smuggling Turkish opium in China, where it was illegal, Col. Perkins left behind many good works and institutions that have contributed a great deal to the city of Boston. While his second home may now have lost some of its elegance, it also persists.

As does the tunnel to the stable. It may be blocked off and look like a carnival attraction, but the passageway Col. Perkins built for his convenience remains as a testament to his great wealth.