Pearl Street was the original address for two of Boston’s most prestigious organizations in the 19th Century. Like many of the lanes on the old Shawmut Peninsula, Pearl Street had many identities and incorporated several other streets into its length.

A Plethora of Names

Originally known as “a highway through the fields” in 1662, it was also described as “Part of Eliakim Hutchinson’s pasture,” then “a lane running to the seaward from the long street up to Fort Hill.”

- After 1708, when Boston stabilized its street names, it absorbed Gridley’s Lane, which went from High Street to Purchase Street. A remnant of Gridley Lane persists as an alley named Gridley Street.

- By 1732, Pearl Street absorbed Hutchinson Street, which was named for the family of the city’s last royal civil governor. Hutchinson Street stretched from High Street to Milk Street and was sometimes known as Palmer Street.

After the Revolutionary War, the name of Thomas Hutchinson was rendered abhorrent by its association to a hated royal governor and a strong opponent of the Sons of Liberty. Every effort was made to obliterate his name from public recognition. (The town of Hutchinson in western Massachusetts changed its name to Barre.) - By 1800, all four long blocks had the name of Pearl Street.

While its name and length remained fixed, however, the nature of Pearl Street changed over the years.

The Ropewalks

The west side of Pearl Street, between Milk and High Streets held seven ropewalks, which were long, straight narrow buildings where strands of material are laid out before being twisted into rope. Two of these structures, owned by Theodore Atkinson, stretched along Congress Street as part of the old Fairbanks pasture. Eliakim Hutchinson owned the other five.

While Mr. Atkinson sold his, the Hutchinson ropewalks remained in the family until 1782, when the city confiscated all of the exiled Governor Thomas Hutchinson’s estate. A fire on July 30, 1794, destroyed all the ropewalks between Pearl Street and Congress, along with the street’s one house, that of a hated Tory customs commissioner, who had fled the city.

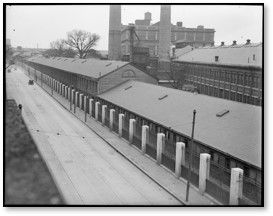

NOTE: A ropewalk structure — the only standing ropewalk still extant in the United States — can be found in Charlestown, where it was part of the old Navy Yard. Designed by Alexander Parris, it made most of the cordage used by the U.S. Navy until it closed in 1973. After years of abandonment, a developer is converting the quarter-mile-long building to the Ropewalk Apartments

Two acres of the newly cleared land were sold to a Rev. Samuel Parker, who served as a go-between for a developer who wanted to build on the land.

Brothers and Institutions

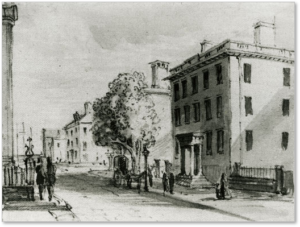

Some of Boston’s most notable residents purchased land cleared by fire to build impressive Federal residences with their stables and beautiful gardens. This enclave of elite homes grew up close to Charles Bulfinch’s nearby Tontine Crescent and was known as the Old South End.

It included the side-by-side homes of brothers James Perkins and Thomas Handasyd Perkins, both of whom made extensive fortunes in the China trade. James lived at Number 13 and gave his mansion the Boston Athenaeum, where he was a trustee, in 1822, a year before his death.

This was the library’s fourth location and the Athenaeum remained in the Perkins house until 1849, when it relocated to its current site at 10 ½ Beacon Street.

In 1833, Thomas Handasyd Perkins followed his brother’s lead and gave his mansion at Number 17 to Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe to house his new community service for the blind. This was a step up from the school’s original location in Dr. Gridley’s father’s house. Created as the New England Asylum for the Blind, the institution was later renamed the Perkins School for the Blind. In 1839, Dr. Howe sold the mansion and moved the school to the former Mount Washington Hotel on East Broadway in South Boston. The Perkins School for the Blind is now located in Watertown, MA.

A View from Fort Hill

The corner of Pearl and High Streets held the three-story residence of future Mayor Josiah Quincy while he served in the state Senate and the Congress. His property stretched up Fort Hill and he liked to walk to the top for its great view of Boston Harbor and the islands. One day, he took Harrison Gray Otis there where they viewed one of Mr. Perkins’s clipper ships coming into the harbor just a year after it had set sail for China.

Behind 17 Pearl Street was located a lecture and exhibition building designed by Solomon Willard. Artist Gilbert Stuart attended the first public art exhibit here in 1827.

The Decline of Pearl Street

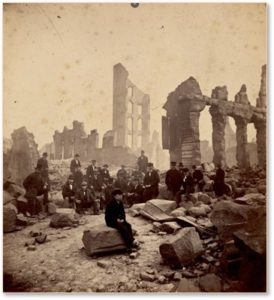

The beautiful homes on Pearl Street, as well as the ones on the adjacent Fort Hill, fell into disrepair the fashionable section of the city moved to Beacon Hill and the newly filled South End. By the mid-19th Century, few of the elegant mansions on Pearl Street remained and those that survived had been converted to commercial use.

By 1844, the section of Pearl Street alongside Post Office Square and down to the waterfront held banks, warehouses, wholesale and retail businesses and insurance companies. The Old South End’s proximity to the harbor water and rail freight transport, better suited it to commercial, rather than residential, uses.

The corner of Pearl and Milk Streets then held a lodging house called the Pearl Street House. The Congress House tavern occupied the northeast corner of Pearl and High Streets.

Every structure on the three blocks of Pearl Street from Milk Street to Purchase Street was destroyed by the Great Fire of 1872. Pearl Street is now part of Boston’s financial district. On the sites of the Perkins mansions, we find 185 Franklin Street and the Garage at Post Office Square.

Pearl Street Today

Pearl Street forms the northeast boundary of the Gridley Street Historic District. This district includes the Richardson Block, which stretches one full block between High and Purchase Streets. Pearl Street now extends one block further than the original.

The street’s extension—really just a pass-thorough between the Hotel Intercontinental and Atlantic Wharf—goes out to the Harborwalk. This is where Griffin’s Wharf, site of the Boston Tea Party, stood originally. While it may be solid land now, you can see the Tea Party Museum from the end.

So much history for such a short street.