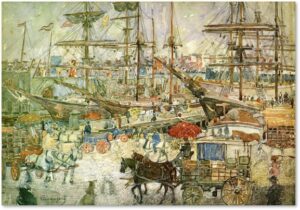

“The East Boston Docks” — Maurice Prendergast

When I was writing last week’s blog post about N.C. Wyeth’s maritime murals, it struck me that the perfect place to hang them would be in Boston’s maritime museum. What could be more appropriate? Unfortunately, well, Boston doesn’t have a maritime museum.

It seems a pity that these four works of art, all of them focusing on the sea, have become invisible in a city that owes its growth and prosperity to the ocean.

Oh, there’s the Tea Party Ship and Museum but that celebrates a particular moment in time that has more to do with the American Revolution than Boston’s shipping industry. A small museum in a privately owned public space on Battery Wharf does a pretty good job with its limited space. Most people don’t even know it’s there, however.

But a big maritime museum, one that honors Boston’s ocean legacy, one that informs, educates, and acknowledges both the good and the bad of how Boston has interacted with the sea? Nope, we don’t have one of those.

Maritime Zilch

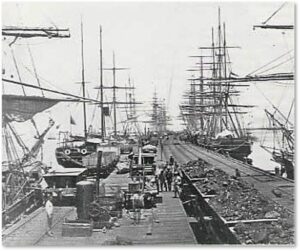

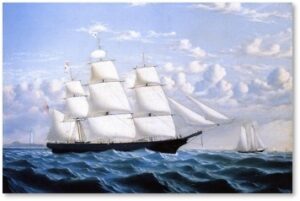

Clipper ships in Donald McKay’s shipyard

Boston’s wealth—along with that of many old families with Beacon Hill fortunes—came from the sea. Whether taking resources from it or shipping goods across it, the Atlantic Ocean was integral to making Boston a city of wealth and prosperity.

Connecticut has the Mystic Seaport Museum. New Bedford’s Whaling Museum memorializes both the whales and the men who hunted them for oil. Maine offers a Maritime Museum of its own way up in Bath. Even New Hampshire’s small seacoast has the Port of Portsmouth Maritime Museum and the Strawbery Banke Museum. Salem honors their heritage with the superb Peabody-Essex Museum.

Boston has—zilch.

Wealth from Over and Under the Sea

Consider that one of the Wyeth murals shows clipper ships, sleek and speedy vessels that were built right here in East Boston and launched from the shipyards of Donald McKay, Smith and Dimon, Brown & Bell, and others.

Consider that one of the Wyeth murals shows clipper ships, sleek and speedy vessels that were built right here in East Boston and launched from the shipyards of Donald McKay, Smith and Dimon, Brown & Bell, and others.

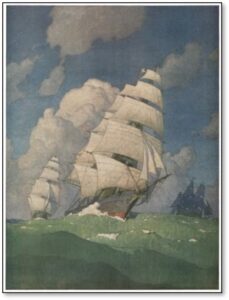

Consider the names of those towering vessels: Flying Cloud, Sovereign of the Seas, Lightning, Ocean Herald, Rainbow, Northern Light. They spoke of speed and pride. Samuel Eliot Morrison called the clippers, “the highest creation of artistic genius in the Commonwealth.”

The clipper ships brought goods to Boston from Europe, the West Indies, South America, China, Hong Kong, Japan, and Imperial Russia. Expensive goods such as porcelain, silk, exotic woods, and ivory decorated the parlors and drawing rooms of Boston’s elite. Furs filled the closets. Tea was brewed in the kitchen and opium filled bottles of “medicinal” pills and elixirs.

Fish, Sugar and Ice

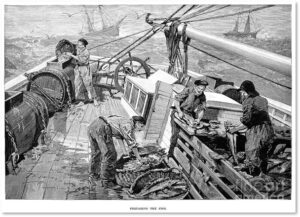

Fishing boats went out of Boston to bring in holds full of Atlantic cod that was eaten fresh here along with haddock, striped bass, sturgeon, herring, alewives, and shark. Cod was more profitably salted and sent to Spain and Portugal, with the lowest grade going to feed slaves in the Caribbean.

Cod fishing in the 19th century

Boston was, for better and worse, the hub of the Triangle Trade that shipped rum, molasses, and slaves in a circular route that stretched from our wharves to the slave markets of Africa’s west coast and the sugarcane fields of the Caribbean.

Frederic Tudor, Boston’s “Ice King,” took winter ice from New England’s ponds, packed it in sawdust in his East Boston warehouse, and shipped it to warm climates all over the world. He not only made a fortune; he created the concept of iced drinks. Think of that as you’re sipping your Dunkin iced latte.

Shipping was so important to Boston that it led to the establishment of insurance companies to cover the significant risks that come with months-long voyages. It also created banks to provide the necessary capital. These built the foundations of Boston’s Financial District. Thus, the First National Bank of Boston commissioned N.C. Wyeth to paint the four maritime murals.

Turning Its Back on the Sea

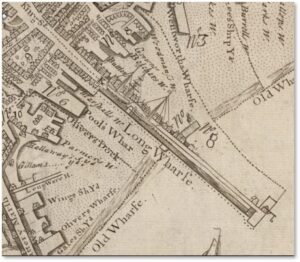

At one time, more than 30 wharves studded Boston’s waterfront. Masts towered over what was then a low-profile city and bowsprits jutted from sailing craft docked for loading and unloading. Those wharves also had wonderful names that spoke of dominance and worlds beyond Boston, such as Russia Wharf, Battery Wharf, Long Wharf, India Wharf, and Lincoln Wharf.

A few of Boston’s wharves

For some reason, though, Boston has chosen to ignore and forget its reliance on the sea. Even though boats still dock at the Fish Pier, the Atlantic Ocean no long plays a starring role in the city’s fortunes.

Even so, that’s no reason to forget it. For decades, the New England Aquarium, a bastion of Brutalist concrete, turned its back on Boston Harbor. You couldn’t even look out a window and see the sea. Fortunately, that has changed.

A Sorry Commentary

Clipper Ship Northern Light by William Bradford

So, here we are: no maritime museum where schoolkids, tourists, and residents can go to learn about Boston’s history with the sea. Nowhere to see ship models, figureheads, photographs, or quarterboards. No videos, movie clips, or demonstrations. Nothing to show them how much their ancestors risked and what they achieved, for better or worse.

Four paintings of the sea are crated up and stored away from everyone. What a sorry commentary.