In last week’s post on the Transcript Building, I mentioned Cornelia Wells Walter, who served as editor of the Boston Evening Transcript for five years. She was the first woman to hold this position on a major American daily paper.

Naturally, I became curious about her. The next day I read an article in the Boston Globe about how the Friends of Hyde Park Branch Library had placed a stone in Fairview Cemetery to mark the grave of Rebecca Lee Crumpler, the first Black female doctor.

Hmmm. Where, I wondered, is Cornelia Wells Walter buried? The question seemed to have an obvious answer. A white woman of means from the right Boston family in the nineteenth century would probably lie in one of Boston’s two garden cemeteries. All I had to do was find out which one.

The Garden Cemeteries

I started with Mount Auburn Cemetery, where generations of Cabots and Lowells have gone to conduct their final conversations with God. Completing the easy search form, I hit Send and waited for a listing to appear. Instead I got a “No results found,” message.

Undaunted, I followed the same procedure for Forest Hills Cemetery. After all, if a woman of Ms. Wells’ accomplishments wasn’t interred in one place she was sure to be in the other. But the same process yielded the same result.

Find a Grave

I turned to another reliable resource, the Find a Grave website. This one requires more information but I had Ms. Wells’ dates from the minimal biography available on Wikipedia: June 7, 1813 to January 31, 1898. I was sure that would do it.

To my surprise nothing came up for a grave in Massachusetts. Nothing. Sometimes, however, people find their final resting place in a family plot or mausoleum outside of the state in which they lived, so I widened my search to the whole of the United States. Nada. Zip. Zilch.

Hunting for Cornelia Wells Walter

Now I was intrigued. What had started as assuaging simple curiosity became a hunt for the grave of Cornelia Wells Walter. Women, even prominent ones, may not get the attention they deserve, in life or in death. A good example of this is the “Overlooked No More” series initiated by the New York Times. The editors are writing obituaries for accomplished women who were ignored in their day by white male obituary writers. So, I went through the process again using the name of Ms. Walters’ brother, Lynde Minshull Walter.

Turns out Mr. Walter lacks even a Wikipedia biography and is mentioned only in the context of the Boston Evening Transcript’s history and his sister’s place in it as the first female editor. Curiouser and curiouser.

Turning to the Husband

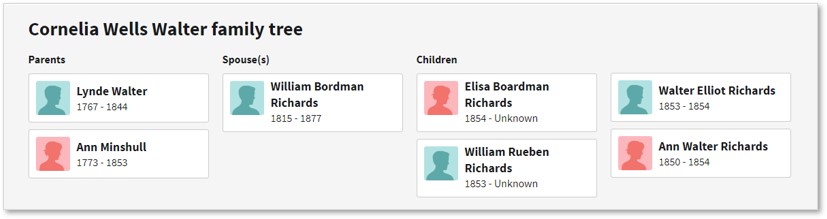

Ms. Walter gave up her editorship when she married William Bordman Richards, a metals dealer, in 1847. Going back through the cemeteries, I searched for a William Bordman Richards but got the same answer: “No results were found for your search term. Please try a different search.” Okay, I’m trying.

I found more information in the husband’s biography. The Boston Museum of Fine Arts has a portrait of Mrs. William B. Richards, painted by Thomas Ball, in their collection, given by Elise Richards, her daughter. In it, she appears to be a woman of wit and intelligence, not to mention wealth as seen in her aubergine satin gown and striking jewelry.

The Back Bay Home

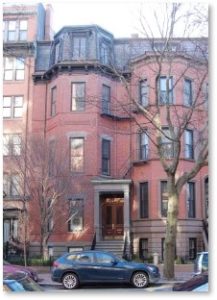

The BackBayHouses.org website provides a good source of information on the homes of prominent Victorian Bostonians and they did not disappoint. Turns out the Richards family lived at #2 Marlborough Street. The house, between Arlington and Berkeley, was built for William and Cornelia Richards by prominent architect Frederick B. Pope.

Presumably, the new Mrs. Richards moved there from the Walter family home on Belknap (now Joy) Street on Beacon Hill. She had lived there with her brother during his long illness and after his death.

BackBayHouse.org also provided the most detailed information yet the couple’s end:

“William Richards died in June of 1877. Cornelia Richards continued to live at 2 Marlborough with their son, William Reuben Richards, a lawyer, and daughter, Elise Bordman Richards.

Cornelia Richards died in January of 1898. William R. Richards and Elise Richards continued to live at 2 Marlborough until his marriage in June of 1908 to Grace Ellingwood Butler. After their marriage, they moved to the Hotel Buckminster at 645 Beacon, and Elise Richards traveled abroad.”

Persisting, I searched Mount Auburn and Forest Hills for William Reuben Richards but came up empty once again. Sigh.

The Boston Globe and Ancestry

Obituaries often contain good information about where the bodies are buried, so I turned to the Boston Globe and searched their records. An obituary for Cornelia Walter appeared (Hallelujah!) but it links to Ancestry.com. That’s a genealogy website that requires a subscription and I don’t have one. I also don’ like being forced to pay for information that should be public or available to someone with a Boston Globe subscription. That’s double dipping.

A Mount Auburn History

But, really,I thought, she HAS to be in Mount Auburn Cemetery because In 1848, Cornelia Wells Walter published a history of that cemetery, called “Mount Auburn Illustrated.” Where else would she be? But, if so, why do they not list her among their “residents?”

But, really,I thought, she HAS to be in Mount Auburn Cemetery because In 1848, Cornelia Wells Walter published a history of that cemetery, called “Mount Auburn Illustrated.” Where else would she be? But, if so, why do they not list her among their “residents?”

I discussed this mystery with my friend, Janet Taylor, who grabbed the baton and ran with it. She found a listing for Ms. Walter in “Notable American Women, 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary, Volume 2.” And that answered the question.

The Death of Cordelia Wells Walter

Cordelia Wells Walter Richards died in her Boston home in 1898 at the age of 84, “apparently from a cerebral hemorrhage.” Her body was cremated and the ashes remained out of sight for 13 years. In 1898, they were interred in Forest Hills Cemetery. As an entry in encyclopedia.com describes her;

“The quality of her work and her sharp mind earned her the admiration of her peers. A crisp writing style characterized Walter’s columns about Boston social and literary life. She spoke boldly through her pen in opposition to female suffrage, unorthodox religious theories, the Mexican War, and the annexation of Texas, and in support of higher education for women. She also traded snide barbs with author Edgar Allan Poe.”

In addition, Ms. Walters’ came from pure Boston blueblood ancestry. She was descended on her father’s side from Thomas Walter of Lancashire, England, whose son, Nehemiah, married Sarah Mather, daughter of Increase Mather. Her grandfather, the Rev. William Walter, was an Anglican clergyman who bolted the city for Nova Scotia during the Revolutionary War, as many Loyalists did. He returned in 1792 to become rector of Christ Church. Today, we refer to it as the Old North Church, where the lanterns were hung that guided Paul Revere and William Dawes on their famous rides.

A Woman Before Her Time

Although as conservative as the Boston Evening Transcript itself, Ms. Walters’ career presaged modern business developments. Because of her “retiring nature” she worked from home and was paid the notable sum of $500 per year for her editorial efforts.($13,432 today)

Does that sound like someone who should be so hard to find?