Back in September, I wrote about how 1919 was Boston’s terrible, awful, no-good year. Which led me to wonder whether any particular month seemed to attract death, disaster, and general bad news. In the calendar of the city’s awful anniversaries, I pick November.

A Concentration of Events

Certainly, terrible things have happened in other months, but November seems to have a concentration of memorable events. They also cross over a number of different categories from earthquake to murder.

Certainly, terrible things have happened in other months, but November seems to have a concentration of memorable events. They also cross over a number of different categories from earthquake to murder.

You wouldn’t expect much to happen in Boston in November. The crush of students entering colleges and universities is over. Vacationing tourists have left. The World Series has ended—not that Boston had much to do with post-season baseball until very recently. The Patriots play in Foxboro. And the Christmas season has yet to swing into full gear.

Ah, but none of those things caused Boston’s November problems. Here’s a run-down by calendar date:

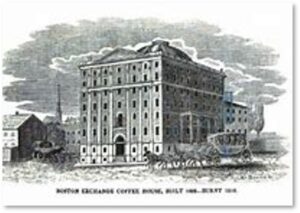

Exchange Coffee House Fire

November 3, 1818 – The Exchange Coffee House was not a small shop but a huge hotel that opened in 1808. Located on Congress Street near State Street, it had a western egress to Devonshire Street. Fire broke out on the southwest corner of the upper story between 6:00 and 7:00 pm.

November 3, 1818 – The Exchange Coffee House was not a small shop but a huge hotel that opened in 1808. Located on Congress Street near State Street, it had a western egress to Devonshire Street. Fire broke out on the southwest corner of the upper story between 6:00 and 7:00 pm.

As the hotel was taller than any other structure in the neighborhood, fire apparatus could not reach the flames. Henry Clay of Kentucky, who was lodging at the hotel, helped to fight the fire by working in the bucket brigade. When the great dome atop the building fell in, flames shot up so high they were seen in Portsmouth N.H.

The Streetcar Disaster

November 7, 1916 at 5:13 p.m. saw streetcar #393 run off the Summer Street bridge into the Fort Point Channel. The Summer Street bridge, a retractile drawbridge, was opening to allow a ship to pass through the channel. The inbound roadway had already slid to its furthest position.

A streetcar loaded with passengers smashed through the gate at the Summer Street drawbridge and plunged off the open span into the Fort Point Channel. The accident killed 47 people.

In downtown Boston, drawbridge gates had ranged from 23 to 48 feet away from the draw on various bridges, with no standards for size, color, distance, or illumination of stop or warning signs. The stop sign for the trolley was not illuminated, and the gates were only 25 feet from the draw.

Operator error most likely caused the accident, as the conductor did not come to a full halt at the designated stop signs. The conductor was not charged with manslaughter, however. Fire engulfed the building in just a half hour.

Charles River Train Wreck

November 26, 1862 — Inadequate signals triggered another train wreck three weeks later when a southbound Boston & Maine Railroad train from Reading drove off an open drawbridge and plunged into the Charles River. Thankfully, the train had stopped at Charlestown, and was traveling very slowly before it plunged into the water.

Although the engine, tender car, and baggage/smoking car fell over the open draw, the remaining passenger car stopped just shy of the edge. It was high tide when the accident occurred and the water was some 60 feet deep. The engine and tender were fully submerged, with the smoking car partially sticking out of the water. Five people died, and two others were initially reported as missing.

An interlocking signal system, alerting train engineers that the next signal on a line will be red, was proposed and eventually implemented after the accident.

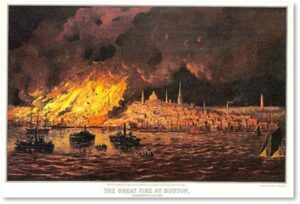

The Great Boston Fire

November 9, 1872 sparked the Great Boston Fire. This disaster began at 7:34 on a Sunday night when a dry goods warehouse at the corner of Summer and Kingston Streets caught fire. It burned for 12 hours, destroying most of the downtown and financial districts and killing 13 people. The fire covered over 800 acres and wiped out more than 770 businesses. It caused $1.4 billion worth of damage (in today’s money).

It would be fair to say that everything that could go wrong did go wrong. There is, however, so much to be said about the causes and consequences of the Great Fire of 1872 that the information fills volumes. Two of them to be precise:

It would be fair to say that everything that could go wrong did go wrong. There is, however, so much to be said about the causes and consequences of the Great Fire of 1872 that the information fills volumes. Two of them to be precise:

- “Inferno” by Anthony Sammarco

- “The Great Boston Fire” by Stephanie Schorow

I highly recommend reading one or both for a sweeping and fascinating understanding of the fire that almost destroyed Boston.

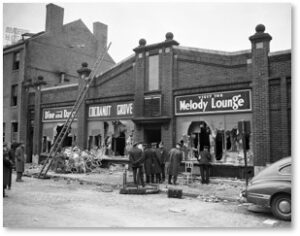

Luongo’s Restaurant Fire

November 15, 1942 saw a large fire at Luongo’s Restaurant in East Boston. After firefighters brought the blaze under control, a wall collapsed, killing six Boston firefighters who were on the building’s second floor and trapping others under debris for over 18 hours. A hot air explosion at the same time blew a half dozen firemen across Henry Street.

This disaster is relatively unknown today because it was overshadowed by the Cocoanut Grove Fire, which occurred only 13 days later.

The Great Earthquake

November 18, 1755 saw what might be the most violent earthquake in colonial history along the Eastern Seaboard. The tremblor, which lasted for a minute or two, was felt from Delaware to Halifax, Nova Scotia. In Boston, it shattered more than 1,500 windows and knocked down over 800 chimneys. The quake also brought down the walls of several brick houses and caused extensive damage to furnishings glass, China, and earthenware.

The Richter Scale did not exist until 1935, so we have no scientific measurement of the 1755 quake. Earthquakes are rare in New England, however, which makes this one even more memorable.

Parkman Murder

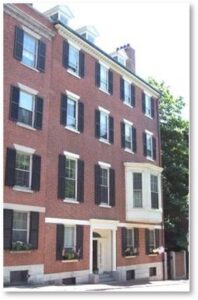

November 23, 1849 was the last day anyone saw Dr. George Parkman alive. Shortly after noon, he left his home on Walnut Street and walked across Beacon Hill to the Harvard Medical School near Massachusetts General Hospital. There he met and argued with Professor John White Webster, about a loan.

Prof. Webster could not meet Dr. Parkman’s demand to repay the loan. In anger, he snatched up a piece of firewood and struck the doctor on the head, later testifying that he “dealt him an instantaneous blow with all the force that passion could give it.”

The professor then dismembered Dr. Parkman’s body and was in the process of burning the pieces when he was arrested. Prof. Webster was tried, convicted, and hanged in August of the following year.

The sensational nature of this murder fascinated the public. It was recently referenced in an episode of the TV series City on a Hill, which is set in Boston. When I heard Kevin Bacon ask Aldis Hodge of he had ever heard of John White Webster, I knew what was coming next.

Cocoanut Grove Inferno

November 28, 1942 saw a wicked blaze that killed 492 people in the 30 minutes from 10:15 to 10:45 p.m. This fire, the worst nightclub fire before or since, had far-reaching effects that we still see around us today: The Cocoanut Grove blaze:

- Changed and expanded fire ordinances and building codes

- Improved how burns were treated in hospitals

- Proved the efficacy of penicillin and began the era of antibiotics.

- Brought the psychological effects of trauma to the forefront

This is another disaster that requires more room and attention than I can provide here. Fortunately, many people have written about it and those books and websites are well worth reading. Warning: Reading about the Cocoanut Grove tragedy may make you cry and vibrate with anger at the same time.

- “Fire in the Grove: The Cocoanut Grove Tragedy and Its Aftermath” by John C. Esposito

- “The Cocoanut Grove Fire” by Stephanie Schorow

- “The Cocoanut Grove Fire” — the National Fire Protection Association

- “The Cocoanut Grove Fire” — Celebrate Boston

Thanksgiving Arguments

That’s more than enough bad things to fill one month. Fortunately, recent Novembers have been more peaceful and I hope that trend continues. We often have family arguments over the dinner table but those rarely rise to disaster level. At least, not for all of us. Let’s keep it that way.