Okay, I am officially not the only person worried about the proliferation of robots and the automation of functions formerly performed by human beings. Some of my readers have asked why I am so opposed to this form of “progress” and whether my concern is based on a Luddite opposition to technology or a resistance to change.

The answer is neither. I’m opposed to automating people out of jobs,–whether it’s with kiosks, robots, or appliances—because it does not augur well for the future. Not for the American economy or the quality of our lives. Plus, I consider very carefully the threat of AI and robots making us biological life forms redundant at some not-too-distant point in the future.

The answer is neither. I’m opposed to automating people out of jobs,–whether it’s with kiosks, robots, or appliances—because it does not augur well for the future. Not for the American economy or the quality of our lives. Plus, I consider very carefully the threat of AI and robots making us biological life forms redundant at some not-too-distant point in the future.

Alarms About Robots

Others are adding their voices to the chorus of alarms that says we should think more than twice about the potential threat posed by rapid roboticization of work. After all, Stephen Hawking—who is much smarter than most of us—warns us that artificial intelligence could spell the end of mankind.

Remember, just because we can do something doesn’t mean we should. Just because Amazon can roll out employee-free grocery stores doesn’t mean that people will enjoy shopping there. Some of us like getting assistance from, or just being in the company of, real human beings.

Here’s a summary of some recent articles on the impact of artificial intelligence and robots on our futures.

Pessimism and Robots

Several articles in the media have expressed negative opinions about robots and automation.

- Forbes: “Amazon’s Grocery Would Eliminate Thousands of Jobs” by Erik Sherman

Mr. Sherman takes a hard-edged view of the business drive to automate as many jobs as possible based on the concept that “Processes are part of bigger systems and need to remain in balance.” That balance can be elusive if each company looks only at its own efficacy and profits on a quarterly basis.

The author also dismisses the idea that technological revolutions create new and better jobs. “During the industrial revolution, people didn’t simply find their former livelihoods disappear and then go on to the next phase of their lives, as we think of it. This is how the Gilded Age and terrible human oppression and widespread poverty on a massive scale happened.”

The New Gilded Age

I find these words particularly relevant given that one percent of our population now lives in a new gilded age of fabulous wealth while jobs disappear and the middle class declines.

Mr. Sherman’s position:

“We need a drastically different way of considering society, individuals, work, and economics. Expecting the constant growth of revenue is like wanting to inhale without exhalation, or consume without stop. It cannot continue. If we don’t find another way, we can expect a societal calamity beyond anything we’ve witnessed, something that would make the Russian Revolution or French Revolution look like a minor altercation, because you cannot toss aside so many people without repercussions.”

Even More Pessimism

- The Washington Post: “The Robot Revolution Will Be the Quietest One” by Liu Cixin

This award-winning science fiction writer takes an even more pessimistic view that puts America in the same situation as Ancient Rome, where wealthy Romans turned all hard work over to slaves, Mr. Cixin’s view gives us Americans passively turning all work over to robots and gradually becoming less competent, less autonomous, and less functional. Why even think if we don’t have to? We’ll just become less and less able to do the simplest things until we can no longer even remember what taking charge of our own lives was like.

I find this pretty easy to imagine. We have become a country where fewer and fewer people know how to create actual objects and use real tools—whether it’s wielding a shovel, handling a screwdriver, or defending ourselves. Some people would find no difference between calling a plumber and calling a plumbot but never think to get under the sink with a wrench themselves.

I find this pretty easy to imagine. We have become a country where fewer and fewer people know how to create actual objects and use real tools—whether it’s wielding a shovel, handling a screwdriver, or defending ourselves. Some people would find no difference between calling a plumber and calling a plumbot but never think to get under the sink with a wrench themselves.

Mr. Cixin’s position:

“Gradually the A.I. era will transform the essence of human culture. When we’re no longer more intelligent than our machines, when they can easily outthink and outperform us, making the sort of intuitive leaps in research and other areas that we currently associate with genius, a sort of learned helplessness is likely to set in for us, and the idea of work itself may cease to hold meaning.”

Optimism and Robots

The Washington Post: “Robots Won’t Kill the Workforce: They’ll Save the Global Economy” by Ruchir Sharma

Mr. Sharma takes a profoundly different view. He sees a declining population leaving jobs to be filled by robots. We’ll need those mechanical service providers because of a dwindling number of real human beings to do the work. Given that the world’s population is still growing at about 1.13% a year (80 million people) I find it difficult to go along with this position. He gives us an extreme long-run view, which is like standing on a hilltop admiring the sunset without looking down at the people going about their lives, for better or worse, on the ground. Given demographic trends, that more immediate view shows a population of old people being tended by geriatricare bots.

Mr. Sharma’s position:

“Women are having fewer children, so fewer people are entering the working ages between 15 and 64, and labor-force growth is poised to decline from Chile to China. At the same time, owing to rapid advances in health care and medicine, people are living longer , and most of the coming global population increase will be among the retirement crowd. These trends are toxic for economic growth, and boosting the number of robots may be the easiest answer for many countries.”

Creation, Not Destruction

The Wall Street Journal: “Automation Can Actually Create More Jobs” by Christopher Mims

WSJ columnist Christopher Mims repeats the assertion that automation will create more jobs than it destroys. This is a pretty steady trope that is aimed at reassuring people that things will be okay in the long run. Not to worry, they assert: more jobs are coming. Alrighty, then.

WSJ columnist Christopher Mims repeats the assertion that automation will create more jobs than it destroys. This is a pretty steady trope that is aimed at reassuring people that things will be okay in the long run. Not to worry, they assert: more jobs are coming. Alrighty, then.

I had to read down to the middle to learn that, “It’s true that technology alters the quality, as well as the quantity, of jobs.” What, exactly does that mean? A few paragraphs later he explains that,

“Disappearing factory jobs have largely been replaced by jobs in the service sector, where highly skilled workers, like doctors and computer programmers, are paid more, while many others see to the comfort and health of the affluent. In the middle, wages have stagnated, helping spawn our current age of populism.”

Well, as long as someone manages the comfort and health of the affluent I guess everything will be okay. After all, someone has to know what to look for when they get underneath the sink and it sure isn’t going to be Harrison Gardner Wentworth IV.

Mr. Mims’ conclusion:

“I’m more optimistic. For all the recent advances in artificial intelligence, such techniques are largely applied to narrow areas, such as recognizing images and processing speech. Humans can do all these things and more, which allows us to transition to new kinds of work.”

Taking the Long View

Both Mr. Sharma and Mr. Mims take the long view that things will work out just dandy in the end. I tend to go with John Maynard Keynes, who said,

“But this long run is a misleading guide to current affairs. In the long run we are all dead. Economists set themselves too easy, too useless a task, if in tempestuous seasons they can only tell us, that when the storm is long past, the ocean is flat again.”

The storm is coming, folks. Batten down the hatches and hope that you don’t end up useless before it’s over.

Robots and the Economy Today

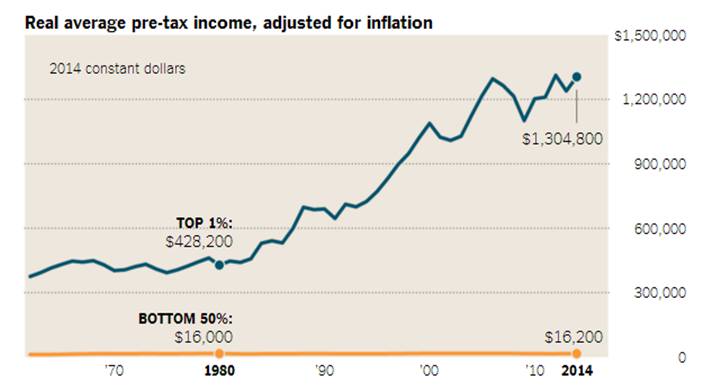

Meanwhile, we might ask, what is the state of the middle class? How are we doing right now, before the Robot Revolution? Are we all doing alright or are some of us more alright than others? We all know the answer to that but here are the charts to illustrate it:

The New York Times: “A Bigger Economic Pie, but a Smaller Slice for Half the U.S.” by Patricia Cohen

“Stagnant wages have sliced the share of income collected by the bottom half of the population to 12.5 percent in 2014, from 20 percent of the total in 1980. Where did that money go? Essentially, to the top 1 percent, whose share of the nation’s income nearly doubled to more than 20 percent during that same 34-year period.”

So I guess the One Percent will be able to afford their servicebots and geriatricare bots and plumbots. The rest of us? Well, we’re going to have to see whether the short term or the long run work out better for us.