Not all sculpture consists of statues carved, molded or fabricated by artists to send a message or please the eye. Some sculpture sticks up like stubborn signposts from the past—pieces of old buildings or infrastructure that were left as reminders of what used to exist there—for better or worse.

Boston has several of these “old bones” that, along with ghost signs and ghost buildings, bring the past into the present for those who know what to look for and what they’re looking at.

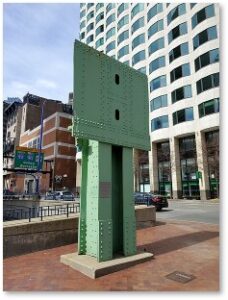

The Dewey Square Pylon

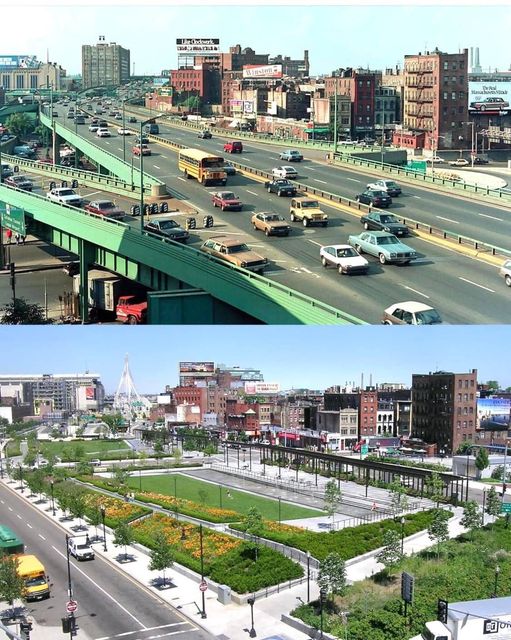

In the Big Dig, the city buried the old Central Artery and demolished its elevated structure. Instead of the ugly expressway, we now have the beautiful Rose Kennedy Greenway. Yet two small, green pieces of highway infrastructure remain.

The Dewey Square Pylon rises at the corner of Purchase and Congress Streets on the south side of the median strip. Formerly part of a support beam for the old John F. Fitzgerald Expressway—informally known as the Central Artery and the Southeast Expressway—it rises green and enigmatic with the Dewey Square Tunnel Vent Building behind it.

A second piece of the highway, Beam 38 or the Central Artery Beam, stands up tall near Quincy Market. An I-Beam from the highway infrastructure, it represents the hundreds of similar structural columns that once occupied what is now a linear park.

The Elevated Expressway

Built in the 1950s, the elevated highway stretched from Dewey Square to North Station. For those Bostonians who remember driving on that dysfunctional road, the surviving piece brings back memories, but not necessarily good ones.

The old expressway was the first elevated highway built in Massachusetts. It was constructed before the U.S. Interstate Act that created our now-ubiquitous Interstate Highway system. This 40-foot -high wall of green steel and concrete also predated federal highway standards.

That made the expressway a challenge to drive on. Its problems included:

- No breakdown lanes

- Severe curves

- Too many on- and off-ramps

- No room to merge onto the highway or slow down to exit

Getting On and Off the Highway

When entering the highway, you had to watch oncoming traffic carefully, find a gap between cars, Then, you would stick your nose out into the right lane, and gun it. To exit the highway, you needed to know exactly where your ramp was and slow down in time, while hoping the driver behind you was paying attention and wouldn’t rear end your vehicle. Good times.

Keep in mind that this was the only way to reach Logan Airport and return again via the Sumner and Callahan Tunnels. The Ted Williams Tunnel, with its straight shot under the harbor, didn’t exist until the Big Dig built it. A smart driver allocated lots of time to sit in traffic on the way to his/her flight.

Loving to Hate It

It’s not easy being green: the expressway was hated by virtually everyone who had to drive on it. Bostonians had many nicknames for this stretch of highway, including the Green Monster and the longest parking lot in the world. Many more-creative names remain unprintable.

At 200 feet wide and 3.7 miles long, it covered 27 acres of prime downtown and waterfront real estate and divided the city from the waterfront that had made it rich and the North End where Boston’s history began. To walk from other parts of the city to the North End’s wonderful Italian restaurants, you had to go through a concrete tunnel often occupied by homeless men and smelling like a urinal. That experience tended to depress one’s appetite.

The Expressway Memorials

The Dewey Square Pylon and the Central Artery Beam both wear the same green paint as the Mystic River/Tobin Bridge and Fenway Park’s left-field wall. The pylon currently bears a plaque that states, “The column remains as a memorial to the elevated highway.”

Funny thing about that, though. Tourists buying souvenirs at Quincy Market don’t even notice the beam. And the young people who work in Boston’s Financial District have no memory of the old Southeast Expressway. They walk past the Dewey Square Pylon every day on their way to the Silver Line, the Blue Line, South Station, the food-truck lineup, and local restaurants. To them, this big chunk of structural metal is just a thing—and a not-very-interesting thing at that.

But I like these iron bones of Boston’s past jutting up from the Greenway. They are pieces of history that refuse to go quietly. They say, “Remember when the city was smaller, darker, lower, and dirtier. We were here then. Things are better now, aren’t they?”

Yes, they are.