Last week I wrote a post about activity in our skies and in the solar system. In today’s post I dig into what’s happening on and under under the surface of planet Earth, where things are changing and shifting. Turns out that some of them are a bit scary.

Volcanic Eruptions

The most visible activities, and the ones most likely to be covered by the mainstream media, are volcanic eruptions. Right now, the lava is flowing in both Iceland and Italy. Mount Etna on the Italian island of Sicily is in its sixth week of violent paroxysmal manifestations. That’s a technical term.

Fortunately, the volcano hasn’t threatened either people or property in the vicinity because these paroxysms expel what’s described as “primitive magma.” This means that the magma remains virtually unchanged from when it is sucked up to when it is ejected from the volcano. Such a rapidly rising magma does not stagnate, which would cause it to seek other ways out and it therefore eliminates the danger of low-lying fractures and subsequent lava flows. Etna is always unpredictable, though, so let’s keep an eye on it.

In Iceland, A shield volcano in Iceland named Mount Fagradalsfall began erupting in mid-March after 6,000 years of dormancy. This eruption follows weeks of “unprecedented” earthquakes and marks the first time there has been an eruption on the Reykjanes Peninsula in almost 800 years.

I find it fascinating to watch as new fissures open and glowing lava pours out. The locals get up close and personal with the new volcano—a lot closer than I would be comfortable doing. You can watch a live feed of the spectacle if you also prefer to keep your distance.

Finally, we hear rumbling coming from Hawaii’s Mauna Loa, the world’s largest volcano,. Small earthquakes on the peak follow months of increased seismic activity. This could lead to the first eruption of Mauna Loa since 1984. (the volcano that flattened a whole neighborhood on the Big Island in 2018 was Kilauea.) That one has been in a continuous state of activity for decades.

Half the Earth is Cooling

Going deeper, we learn that one side of Earth’s interior is cooling much faster than the other side. Scientists from the University of Oslo conducted research that used computer models of the last 400 million years to calculate how “insulated” each hemisphere was by continental mass. That’s the part of Earth’s surface covered by land rather than ocean.

While the core of Planet Earth has been cooling naturally over millennia, the scientists were surprised by how unevenly the heat is dissipating. The models examined a grid pattern established over the Earth’s surface and measured how much heat each grid cell contains over its long life. They found that the Pacific side has cooled much faster because the seafloor is a lot thinner than the bulky landmass. That volume of cold water quenches the temperature of the core below it.

While the core of Planet Earth has been cooling naturally over millennia, the scientists were surprised by how unevenly the heat is dissipating. The models examined a grid pattern established over the Earth’s surface and measured how much heat each grid cell contains over its long life. They found that the Pacific side has cooled much faster because the seafloor is a lot thinner than the bulky landmass. That volume of cold water quenches the temperature of the core below it.

I’m not sure why this came as a surprise to the scientists as it seems like common sense to me. But the research over 400 million years did cover almost twice the length of time of previous studies (230 million years) and went back over 400 million years.

While this information is interesting, I don’t think it gives us anything to worry about in the short term. Unless the planet starts wobbling, we’re probably okay.

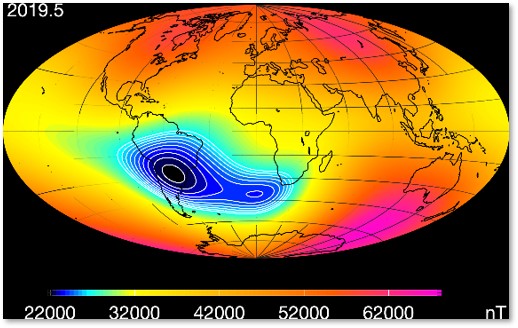

Earth’s Magnetic Field Weakening

Deeper still, we find that Earth’s magnetic field is weakening in a region stretching from Africa to South America. The European Space Agency (ESA), which deploys its Swarm satellites to measure the weak area, have dubbed it the “South Atlantic Anomaly.”

An ESA press statement declares that Between 1970 and 2020, the minimum magnetic intensity in the abnormal region in the South Atlantic has plummeted from 24,000 nanoteslas to 22,000 nanoteslas between 1970 and 2020. Nanoteslas are the unit of measurement for the strength of Earth’s magnetic field, or its magnetic intensity.

Is this important? You betcha. Earth’s molten core generates the planet’s protective magnetic field. This field guards against solar winds that carry damaging charged particles and guides the navigation systems that direct everything from smart phones to satellites. More importantly, it protects us from solar winds and the sun’s ultraviolet radiation. In other words, we need it and we need it to remain strong.

What does this weakening in the South Atlantic Anomaly men for us? It doesn’t seem good. What can we do about it? Probably nothing. I’m not going to stay awake worrying about it.

What’s Going on Around Us

I have started writing these posts because (A) I’m interested in a lot of things and (B) there’s so much more going on around us every day than work, politics, a divided country, and partisan bickering. Because I can’t travel overseas until the pandemic has ended, I look around me at what’s going on elsewhere. I see things happening on Earth, or under it, or above it.

Science delivers information that, quite often, we have never known before. What it tells us provides a kind of travel and I’m happy to share it with you.