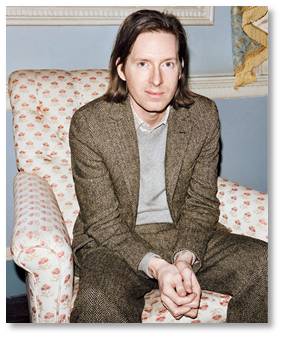

Consider me one of those people who, over time, have been less than charmed by Wes Anderson’s quirky oeuvre. Until now. I’m happy to report that The Grand Budapest Hotel is quirky in a good way, charming most of the time, funnier than I anticipated, and completely engaging.

Consider me one of those people who, over time, have been less than charmed by Wes Anderson’s quirky oeuvre. Until now. I’m happy to report that The Grand Budapest Hotel is quirky in a good way, charming most of the time, funnier than I anticipated, and completely engaging.

I am even happier to note that Mr. Anderson has abandoned his annoying mannerism of directing perfectly good actors to speak in a dreary monotone worthy of a middle-school class play. In TGBH, an astonishing cast of extraordinary range is allowed to employ their art, using inflection and emotion to add a depth of character that has been missing in his previous movies. And this is a very good thing because the movie is a mystery wrapped in a flashback inside a memoir. Each of these stories, separate but connected, is filmed with its own lighting and with what critics tell me is the aspect ratio. I don’t have the technical chops to recognize this but I could definitely tell the difference between how the segments appear.

The Grand Budapest Hotel is charming, witty, absurd, droll, intriguing, thoughtful, whimsical, witty, and sarcastic all at once. It is as implausible a layering of attitude and emotion as the improbably vertical pastries called Courtesan au Chocolat provided by Herr Mendl in pink boxes wrapped with blue ribbon.

At its heart, the movie is a coming-of-age story, as most of Mr. Anderson’s films are, with a strong sub-plot of loyalty rewarded. The demand for that loyalty is often more self-serving than altruistic, especially on the part of Ralph Fiennes’s hotel concierge Gustave H. but the reward follows nonetheless. Both morally shaky and sexually ambiguous, M. Gustave somehow balances elegance and refinement with casual vulgarity and an equally careless attitude toward other people and even a cat. In many ways, he embodies aspects of the charismatic sociopath: narcissistic and often oblivious to the dangers into which he drags young Zero Moustafa (Tony Revolori). Yet he is loyal. How else could a lobby boy with zero experience, zero education and zero family succeed in . . . ah, but that would spoil the fun.

TGBH is reminiscent of both the Marx Brothers films and the early Woody Allen movies. For more detailed reviews, I direct you to the pros:

- The Wall Street Journal: “Multistoried ‘Hotel:’ Wicked, Wild Wes” by Joe Morgenstern

- The Washington Post: “The Grand Budapest Hotel Review” by Ann Hornaday

- The Boston Globe: “Anderson’s imagination checks into ‘The Grand Budapest Hotel’” by Ty Burr

- Screenrant: “The Grand Budapest Hotel Review” by Sandy Schaefer

Dysfunction on Display

What both intrigues and puzzles me about Wes Anderson’s movies is the way in which he creates seriously dysfunctional characters whose odd behavior is accepted as funny or is ignored by the critics who love his movies. This was on full view in The Royal Tenenbaums, a film whose characters were so bizarre I could barely stand to watch it. But it was Moonrise Kingdom that really set me off.

The critics loved Moonrise Kingdom—loved it, every one! They called it luminous and magical among other adulatory adjectives. Well, I enjoyed much of it as well but something began to gnaw at me from the beginning and got worse as the movie progressed. It was the character of Suzy Bishop (Kara Hayward). She and Sam (Jared Gilman) are a girl and boy who run away from home and camp out by the ocean until discovered by a search party made up of the panicked adults in their lives. Here’s Mr. Anderson’s coming-of-age story being played out again, yet there is a significant difference between how the two children appear and behave.

Sam is a little boy who looks his age, wearing a scout uniform and a coonskin cap. He has little boy concerns, worries and challenges. His life is pretty much okay — until Suzy arrives. Suzy, however, is a junior seductress. She wears a very short skirt that exposes much of her long legs and blue eye shadow worthy of a Maybelline model. Her body is displayed in a way that is clearly and inappropriately sexualized for her age. Suzy, who keeps to herself at home, is also angry, defiant, and offensive to her parents. But why? The movie never gives an overt explanation — but wait, there’s more.

Suzy is the one who persuades Sam to run away and masterminds the operation. Once caught up in their plot, he uses his scouting skills to ensure that their escape is done properly. and safely When they have established their camp by the ocean, he wants to camp out scout-style and she wants to play house. She initiates a first kiss along with the sexual behavior that follows it. She’s the first one to take off clothing. The adults who find them are outraged but no one asks why this has happened. It’s accepted as a coming-of-age kind of thing. But is it, really?

The Normality Bias at Work

I know that children who display aggressive sexual behavior that is inappropriate for their age don’t get it from TV shows. They learn it from adults who abuse them and then bully, threaten or bribe them into keeping the abuse a secret. So at some point in Moonrise Kingdom, I began to look at Suzy’s father, Mr. Bishop, (Bill Murray) with a whole different set of eyes. His behavior seemed increasingly furtive and guilty—fearful of what the search party would actually discover. Is this what Mr. Anderson intended or am I seeing something that wasn’t there?

I would like to think it was the latter, given that no one else picked up on it, but I don’t think that was the case. I think Mr. Anderson skated this successfully past the critics and the audience because of the normality bias. While this concept is defined in terms of disasters and legal decision making, I think it affects us all on an everyday basis. As human beings, we have a very strong need to see others around us as normal people, sometimes despite clear evidence to the contrary. In the New York Times, Manohla Dargis went so far as to call Suzy’s behavior “existential despair” instead of child abuse — as if it’s normal for a 12-year old child to despair of life.

Suzy Bishop and her father are not normal people. Neither is M. Gustave despite all the reasons we find him quirky instead of abnormal and charming instead of dangerous. In Howie Kahn’s @WSJ interview, “The Life Aesthetic,” he reports that Wes Anderson based the character of Gustave H. on a “longtime friend.”

Reviews of Mr. Anderson’s films — and the interview as well — focus on style. That’s understandable as his films are all very different stylistically and he puts a lot of time, attention and labor into creating exactly the right style. But Mr. Anderson walks a fine line with his characters, a line that seems invisible to most of his viewers. Where, exactly, does he draw the line between style and substance?

Is it actually the line between style and reality?