In yesterday’s post, I described the ceiling fresco painted over the Grand Staircase at the Prince-Bishop’s Residenz in Würzburg, Germany by the 18th-century Italian artist Giovanni Battista Tiepolo. I ended with the fire-bombing of that city by the Royal Air Force on March 16, 1945.

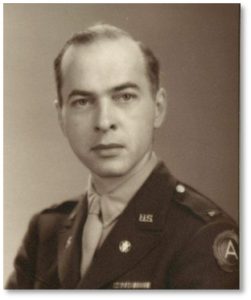

What happened to Tiepolo’s magnificent ceiling? Enter one of the Monuments Men: Lt. John Davis Skilton, Jr. He didn’t look like George Clooney or Matt Damon in the movie of that name, but he was the real deal and he had his work cut out for him.

John Davis Skilton, Jr.

John Davis Skilton, Jr. could not have been more American. Hailing from Connecticut, he held a degree in Art History from Yale. He worked in Washington D.C.’s National Gallery and, for a time, guarded that collection as curator when it was moved to Biltmore House in Asheville, NC, for safekeeping during World War II. Mr. Skilton was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1943, landed on Omaha Beach, and was assigned to the “Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives” section in 1945.

The MFAA operated behind enemy lines to protect cultural monuments and treasures from destruction during World War II. Lt. Skilton became a Monuments Specialist Officer in Europe, where he rescued works of art in France and Germany. Lt. Skilton arrived in Würzburg after the bombing with the assignment of saving the Tiepolo frescoes over the Grand Staircase and in the Imperial Hall (Kaisersaal).

Exposed to the Elements

The timber roof of the palace had been destroyed, blown off by the bombs landing on the parade ground in front of the palace. Balthazar Neuman’s cove vault—with Tiepelo’s frescoed ceiling—held up. Against all odds, it survived the bombing, the fire that followed, and the war.

Now, however, the top of the ceiling was exposed to the elements. Left that way, rain and wind would destroy what the RAF bombs did not. Rain poured down on the day Lt. Skilton arrived in the city and it continued raining for the four months he spent in Würzburg.

To save the frescoes, he needed to build a roof over Balthazar Neuman’s cove ceiling to replace the one that Allied demolished. And to construct a roof, he needed wood, a commodity difficult to find in post-war Europe.

Building a New Roof

Here’s how the Monuments Men Foundation describes his efforts:

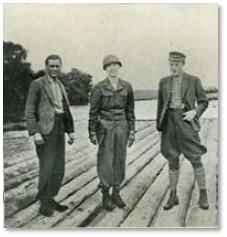

“For several weeks, Skilton collected lumber to repair the roof. He eventually found a stash of logs near Ochsenfurt, which he floated down the Main River to Heidingsfeld. After personally financing a sawmill to cut the logs, Skilton supervised a team of German architects, engineers, and laborers who worked diligently to repair the roof before rains could destroy the magnificent ceiling. The project, begun under Skilton’s supervision in 1945, was not completed until 1987.”

At the completion of the Residenz tour, a visitor sees an historical tribute to John Davis Skilton, Jr. and his accomplishment in saving these masterpieces. It mentions how he badgered quartermasters for ropes, tarpaulins and other materials to cover the new roof. I would have taken a photo of the exhibit but for the palace’s “no cellphones” rule.

If you find this story interesting, you can read the detailed, first-person account of Lt. Skilton’s arrival in Würzburg and his impression of the Tiepolo ceilings, along with the rest of the story, in “The Merchants of Light,” an unpublished novel by Marta Maretich. I’m going to read the book and get the whole scoop on how Lt. Skilton saved the Tiepolo ceilings for the world.

After the War

After the war ended, Mr. Skilton returned to the United States, where he pursued a long and successful career in the art world. Here, he lived in obscurity outside his field. Europe, however, recognized the importance of his efforts with the Monuments Men.

After the war ended, Mr. Skilton returned to the United States, where he pursued a long and successful career in the art world. Here, he lived in obscurity outside his field. Europe, however, recognized the importance of his efforts with the Monuments Men.

France awarded him the Medaille de la Reconaissance Francaise and made him a Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur for his wartime services. He received the Verdienst Kreuz, First Class from West Germany as well as highest honors from Bavaria and the City of Würzburg.

John D. Skilton, Jr. died January 22, 1992 in Fairfield, CT, and is buried in Homewood Cemetery in Pittsburgh, PA. His gravestone is modest and gives only the dates and places of his birth and death.

The Prince-Bishop’s Residenz in Wurzburg, with its priceless art treasures restored, is now a World Heritage Site.

If you visit Wurzburg on your own or, as we did, on a Viking River Cruise, don’t miss this excursion.