I recently read with interest an article on lost architectural icons that appeared in CNN’s Style section. “Remembering America’s Lost Buildings” by Kevin D. Murphy, Carol Willis, Daniel Bluestone, Kerry Traynor, and Sally Levine asked five architecture professors to answer the question, “What one American structure do you wish had been saved?”

Choosing a Variety of Buildings

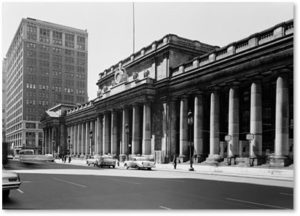

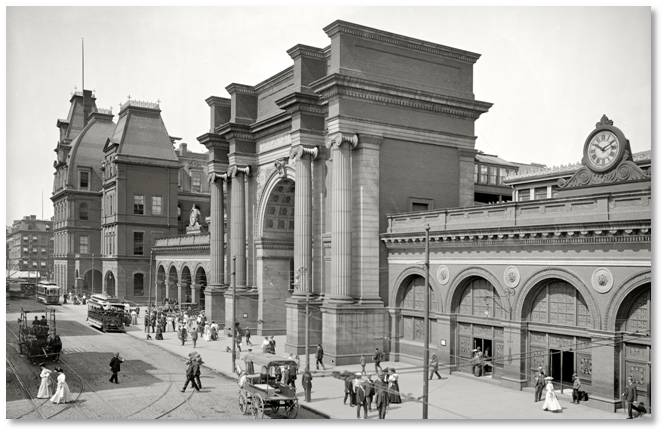

The professors chose a variety of buildings, from enormous to modest. The list includes, as one would expect, the old Penn Station, the Chicago Stock Exchange, and the original Waldorf Hotel.

One notices, however instances where local bias affected whether a building was saved or demolished.

The Mecca Apartments — Chicago

Daniel Bluestone of Boston University chose Chicago’s Mecca apartment building. Designed in 1891 by Edbrooke and Burnham, this innovative 96-unit residential structure incorporated a landscaped courtyard open to the street. Residents of the 96 units entered their apartments on open galleries that encircled two atria with skylights. The skylights lit the interior and the open space provide fresh air and room to breathe.

Between 1912 and 1913, Chicago’s demographic makeup shifted, however, and the city’s expanding Black Belt overtook “the Mecca.” The new residents also enjoyed the building’s light and space but the Armour Institute nearby grew concerned about attracting new students to a campus “located in the heart of the black community.”

Race vs Influence

The institute, now the Illinois Institute of Technology, purchased the Mecca in 1938. Years of legal fighting and community protest followed, as residents fought to save their home. This included legislation that would have saved the building. Alas, Governor Dwight Green vetoed the bill and the Mecca came down in 1952 – a mere 61 years after its construction.

Thus, did racial bias take down an architecturally significant building. The people of color who lived in and appreciated the Mecca lacked the clout of a university that wanted to put a firewall between their campus and the black community.

For a picture of the building that replaced it, read the article.

The Rachel Raymond House – Belmont MA

Vanderbilt University Professor Kevin D. Murphy chose the Rachel Raymond House in Belmont MA. I had read about this preservation battle when it occurred but then forgot about it.

Architect Eleanor Raymond designed this family residence for her sister, Rachel, in 1931. Its modernist style of abstract blocky shapes full of right angles incorporated flat roofs, steel-sash windows and metal railings.

I don’t typically find modernism an attractive style—it makes me think of living in a Crate & Barrel box. But the distinctive house lays claim to the earliest residence of that style in New England.

Unfortunately, the Rachel Raymond House ran up against the expansionist aims of yet another institution of higher education. The Belmont Hill School, a private school for boys, purchased the Rachel Raymond House and demolished in in 2006. The efforts of many preservationists, notwithstanding, the house designed by a woman came down after just 75 years.

The Bauhaus Survives

In nearby Lincoln, MA, however, the Walter Gropius House stands proud and well maintained in a meadow, open to the public as a house museum. This house, designed by the founder of the Bauhaus School, went up in 1938, seven years after Eleanor Raymond’s modernist residence. One was razed; the other became a museum.

Here’s the portion of the article that really knocked me over, though:

“So why did these two important houses receive such vastly different treatment?

The obvious answer is that the work of women architects has been consistently undervalued. In her book “Where Are the Woman Architects?,” architectural historian Despina Stratigakos points out that many female architects seem to possess fewer opportunities for advancement than their male counterparts. One source of the problem, according to Stratigakos, is a dearth of prominent female role models in the field.”

Wait. What? It seems to me that you can’t have “prominent female role models” unless they first have opportunities for advancement. One comes before the other. To put it this way is like saying that minor league hitters have fewer opportunities to move up to the majors because there aren’t enough big hitters already in the Show.

Follow the Money

One cannot blame all demolitions on bias. Usually financial considerations trump all others and Follow the Money is the first rule of demolition. Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue used to be lined with the mansions of the rich and powerful. When these families moved on to more fashionable areas, developers found more lucrative uses for these prime real estate locations.

The Astor Mansion gave way to the original Waldorf Hotel, which was replaced in turn by the Empire State Building. Money talks and buildings fall.

My Personal Selection

The article did get me thinking, however, about what building among Boston’s many lost treasures, I would have chosen to save. After paging through “Lost Boston” by Anthony Sammarco and “Lost Boston” by Jane Holtz Kay, I settled on the structure that came to mind right from the start: Union Station.

I like Boston’s old Union Station for its size, its imperial chutzpah, its architectural distinction and its colossal columns. The building’s very enormity belied Boston’s Puritan tendency toward things small, plain, and understated. No shrinking violet, Union Station proudly declared its status and importance on the scale of ancient Rome.

Rising and Falling on Causeway Street

Designed by Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge in the Beaux-Arts style, it rose from Causeway Street in 1893. Union Station served the needs of multiple railroad companies, just as an airport provides gates to many different airlines. Mr. Sammarco describes Union Station, also called North Station as:

“ . . . dominated by an entrance that had an enormous coffered archway in a Roman-inspired triumphal arch with four monumental Ionic column set on massive plinth bases and a heavily bracketed cornice.”

See what I mean? Two huge clocks kept passengers on schedule and told passersby the time of day. Clearly, Union Station had a strong presence in the city.

My Name is Ozymandias

Despite its size and importance, Union Station was demolished in 1927 to make way for a “newer and larger,” but certainly not more impressive, North Station and the Boston Garden Arena. Neither had any pretensions to imperial majesty. Not many buildings in Boston then or now give one the opportunity to use adjectives like imperial, massive, and monumental.

The fate of Union Station always makes me wonder what happened to that massive stonework. The columns, the plinths, the arch and even the clocks had to have gone somewhere. No wizard apparated them to another dimension. We know that large parts of old Penn Station got dumped in the New Jersey Meadowlands. Were the building blocks of Boston’s Union Station incorporated into other structures or unceremoniously discarded in a tidal marsh somewhere?

Does anyone know?

Related Post: Architectural Art: Demolition and Salvage