Leave it to an academic to look at the state of the job market and confuse cause with effect. Why am I not surprised? In today’s The Wall Street Journal, Glenn Hubbard asks the question, “Where Have All the Workers Gone?” My first reaction was, “If you have to ask, you just don’t get it.” Then I read the article and confirmed that Mr. Hubbard really doesn’t get it.

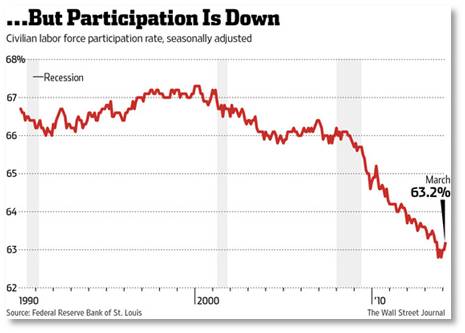

First, he notes “the big puzzle” that looms over the U.S. economy” “only 53.2% of Americans 16 or older are participating in the labor force, which, while up a bit in March, is down substantially since 2000.” I know a lot of people whose response to this would be, “Well, duh.”

Who is Glenn Hubbard? He’s the dean of Columbia Business School, chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors under President George W. Bush and economic advisor to Mitt Romney’s presidential campaign. With Tim Kane he also authored, “Balance: The Economics of Great Powers from Ancient Rome to Modern America,” which will be released in May. Given the sweep of this topic one might expect Mr. Hubbard to have greater perspective on the American economy but his article demonstrates that he is firmly mired in a political point of view.

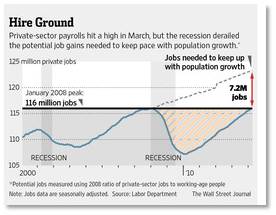

Today’s @WSJ also includes an article on the current jobs report by Jefferey Sparshott: “U.S. Reaches a Milestone on Lost Jobs,” which further discusses the country’s low labor force “participation rate.”

Today’s @WSJ also includes an article on the current jobs report by Jefferey Sparshott: “U.S. Reaches a Milestone on Lost Jobs,” which further discusses the country’s low labor force “participation rate.”

The Power of Words

Because words have power, I want to address the terms used in these two articles: lost jobs, low participation rate, and poor work incentives.

Lost Jobs: In the Great Recession, jobs were not “lost.” They did not wander off into the wilderness or disappear into a crowd so that employees could not find them. Jobs were cut, slashed, eliminated, wiped out, or demolished. This was done intentionally by senior management to reduce costs, boost efficiency, and improve the bottom line. Sometimes executives took this action to help the company survive, sometimes they were just frightened, and sometimes they did it because everyone else was doing it. Sometimes it was done for reasons, like moving entire departments to another state, that increased expenses but seemed—to someone—like a good idea at the time. But no one dropped these jobs off at the side of the highway so they couldn’t find their way home.

Low Job Participation: Both Mr. Hubbard and Mr. Sparshott seem to believe the employees make capricious choices about whether to keep working or to “drop out” of the work force. As though they have really nothing to gain one way or the other and thus ponder the myriad possibilities. Students may drop out of college because it is their choice to do so but the choice on whether an employee gets to keep his job is up to management, not to him. Thus, the worker does not “drop out;” he’s pushed out. Also, the authors seem to believe that there is no connection between jobs being hacked away from companies like chopping ice off the driveway and low labor force participation. But the two are connected.

Low Job Participation: Both Mr. Hubbard and Mr. Sparshott seem to believe the employees make capricious choices about whether to keep working or to “drop out” of the work force. As though they have really nothing to gain one way or the other and thus ponder the myriad possibilities. Students may drop out of college because it is their choice to do so but the choice on whether an employee gets to keep his job is up to management, not to him. Thus, the worker does not “drop out;” he’s pushed out. Also, the authors seem to believe that there is no connection between jobs being hacked away from companies like chopping ice off the driveway and low labor force participation. But the two are connected.

Poor Work Incentives: Well, if you believe that working or not working is a capricious personal decision then you also believe that people need incentives (usually from the government) to get a job or keep a job. If your basic premise is that people are lazy and prefer not to work, I suppose this all makes sense. To people who live in the real world, who need a paycheck—or a bigger paycheck—this attitude would be a joke if only it were funny.

Where The Workers Have Gone

So where have all the workers gone? Mr. Hubbard finds that they have scurried to three places:

Retirement: He attributes one quarter to one half of the decline in labor force participation since 2008 to retirements. Well, people do tend to retire when they get old and Baby Boomers, like everyone else, get older every year. That does not mean that these folks want to retire or can afford to retire, however. Not everyone has a cushy university salary and tenure to protect it. Not everyone is looking forward to royalties from book sales.

Many people who are 60 and over would love to keep working or need to keep working but, guess what? They were laid off, RIFed, driven out, kicked to the curb, dumped, de-accessioned, pushed out or otherwise told in no uncertain terms that they were no longer either needed or wanted in the work force. This tends to decrease participation, don’t you think?

Poor Work Incentives Created by Public Policies: Really. He really says this. Because we all know that corporations depend on public policies to keep workers coming in every day. It used to be that companies offered good salaries and benefits as incentives for the best, most talented, most experienced workers to walk in the door and stay there. I guess this is old hat.

Poor Work Incentives Created by Public Policies: Really. He really says this. Because we all know that corporations depend on public policies to keep workers coming in every day. It used to be that companies offered good salaries and benefits as incentives for the best, most talented, most experienced workers to walk in the door and stay there. I guess this is old hat.

Now the same companies who embrace the “free market” and who want government to butt out of their business by lowering corporate taxes, slashing regulations, and paying no attention when they offshore their jobs to other countries or pollute the environment in this one now need government to step in and incentivize their workers. Go figure.

Two of the reasons Mr. Hubbard cites for these disincentives are (1) a “greater propensity to seek disability insurance” and (2) extensions of unemployment insurance. While he acknowledges the importance of keeping income support in place, (Phew!), he says that extensions, “also lengthen spells of unemployment, potentially making workers less attractive to employers going forward.” Of disability insurance he says that for some it, “has become an incentive to give up on work.” Note the wording. This is where cause and effect get turned around.

In his mind, people stay on unemployment not because they can’t find a job and like to eat but because unemployment benefits are so generous the recipients would rather just loaf around eating bon-bons and watching soap operas than get a job. People on disability are just looking for an excuse not to work. Again, you hear the belief that people are basically lazy and need to be desperate and starving before they will, grudgingly, accept a job. I am willing to bet that Mr. Hubbard has never collected unemployment insurance at any point in his academic career. Had he done so, he would understand how difficult it is to make ends meet on this fraction of one’s usual income—which is also taxed.

The reality in today’s economy is that people go on unemployment, apply for disability, or retire early to collect Social Security because they can’t find a job and have no alternatives. The cause is lack of jobs, the result is reliance on federal benefits, not the other way around.

Solving the Puzzle

To be fair, Mr. Hubbard does offer suggestions on how to solve the puzzle of low labor-force participation by “easing the return to work.” Again, really. I know many people who don’t need to be eased back into the workforce. They would jump in—tomorrow—with both feet if only they had the opportunity. And, oddly enough for a former member of a Republican administration, most of his solutions involve changes to government policy—and they include raising taxes.

One of his suggestions, is to “encourage low-wage workers” and he would “rethink the federal government’s wider role in the labor market.” Well increasing the minimum wage would serve as a pretty big encouragement. So would increasing hiring so low-wage workers have the opportunity to move to a job that pays a better salary or offers a career track. We don’t need government for that.

And he brings up the ever-popular issue of re-training. Perhaps because I live in Massachusetts, a state with many world-class institutions of higher education, I look askance at this one. Most of the job seekers I know or have encountered have very good educations—and years of experience to back up their degrees.

A Different Perspective

For a different perspective I refer you to Annie Lowrey’s New York Times article, “Out of Work, Out of Benefits and Running Out of Options.” In it you will meet Abe Gorelick who has, “. . . decades of marketing experience, an extensive contact list, an Ivy League undergraduate degree, a master’s in business from the University of Chicago, ideas about how to reach consumers young and old, experience working with businesses from start-ups to huge financial firms and an upbeat, effervescent way about him.” What he has not had for a year—you guessed it—is a job. So what is Mr. Gorelick doing to ease himself back into the workforce? “He is now working three jobs, driving a cab and picking up shifts at Lord & Taylor and Whole Foods.”

This is the face of unemployment that I have seen—not Mr. Hubbard’s view from the ivy-covered towers of Columbia University. I do agree with his assessment that this is a structural problem, not a short-term one. And I also agree that our government and both political parties have been ignoring the issue of long-term unemployment with its attending low labor force participation.

But please don’t tell me that the unemployed are a lazy shiftless lot who need a combination of carrot and stick to drive them back into the work force. We need companies to start hiring. And it’s not the federal government’s fault that they are not doing so.