Back in June, Susanne and I each wrote a post about why French women don’t get fat. Suze focused on a book about the topic while I dealt with the quality and purity of the local food supply.

Back in June, Susanne and I each wrote a post about why French women don’t get fat. Suze focused on a book about the topic while I dealt with the quality and purity of the local food supply.

- Why Don’t French Women Get Fat? – Susanne

- Why French Women Don’t Get Fat – Aline

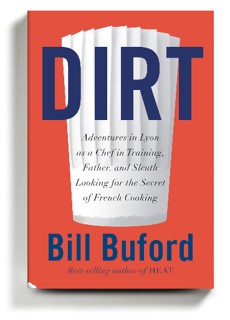

Recently I have been reading a book that adds a third perspective—that of American parents living in France and watching how their twin sons learn about food. The book bears the unfortunate name of Dirt Who, writing a book about French gastronomy would name it “Dirt?” Well, Bill Buford would and did.

Learning the Art of French Cooking

Mr. Buford is an American writer who conceived the idea of moving to France to learn the art of French cooking. He thought three months would do it. Incroyable! He had the advantage of knowing some (very) prominent French chefs here in the U.S. and thought they could help him in his quest.

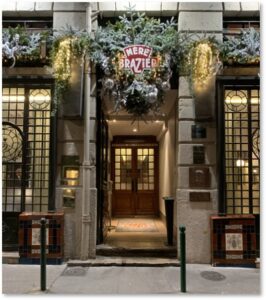

In this book, you learn how difficult it is to get permission to move to France and the beauracracy of getting a work visa there. Étonnant! But he succeeds in his quest to do a stage, or internship, in a small restaurant called La Mère Brazier in Lyon, home of Chef Paul Bocuse and the novelle cuisine. Why he wanted to do this strains my understanding. Working from 8;30 a.m. until midnight in horrific conditions, often with toxic men, is not my tasse de thé.

In this book, you learn how difficult it is to get permission to move to France and the beauracracy of getting a work visa there. Étonnant! But he succeeds in his quest to do a stage, or internship, in a small restaurant called La Mère Brazier in Lyon, home of Chef Paul Bocuse and the novelle cuisine. Why he wanted to do this strains my understanding. Working from 8;30 a.m. until midnight in horrific conditions, often with toxic men, is not my tasse de thé.

Mr. Buford moves his wife, who speaks fluent French, and his twin three-year-old sons, George and Frederick, to Lyon. There, after a stint in France’s pre-eminent (and only) cooking school, he finds a restaurant in which to work as a stagiaire, or intern. His wife enrolls les deux garçons in the local school. They speak no French but this is pas de problème for children of that age, who pick up languages quickly.

NOTE: I am quoting extensively from “Dirt” as only Mr. Buford’s words

convey something any American parent will find astonishing.

Learning More Than the Three Rs

Over time, Mr. Buford learns that his sons are learning more than the three Rs in that local school, l’École Robert Doisneau, which he describes as simply as “underfunded, overcrowded public school.” He mentions that “It had roof leaks, an asphalt playground that was breaking up and weeds growing through the cracks.” So, erase any image of a fancy private school from your head.

There, like all French children, they also learn how to eat.

His wife, Jessica, tells him that the boys are graded for how they eat and how well they behave in the canteen. This is part of the French belief that eating well can be taught, and they apply it to all schoolchildren across the country.

The School Menu for French Children

First, comes what they eat.

“The canteen menu was posted each week outside the school’s entrance: three courses, plus a produit laitier, a milk product—yogurt of cheese. There were no repeats, a feature so radical that I am compelled to repeat it: No menu was ever served twice during the school year. (Jessica, who had become a member of a parent-teacher executive committee, discovered that, at strategic intervals, certain foods are repeated—turnips, kale beets—to help children become familiar with them.

“The first course would be a salad—say, grated carrots with a vinaigrette. George’s current favorite (Carottes râpée!”), which he asked his mother to make for dinner. The second, the plat principal, might be a poulet with a sauce grand-mère (made from the broth that the chicken had been cooked in.) There was a cooked vegetable (maybe Swiss chard in a béchamel sauce), and a fruit or dessert. The boys’ favorite had been moelleux au chocolat, hard on the outside, like a brownie, and soft in the middle, with a warm chocolate meltingness.”

American parents will notice the difference immediately. No pizza, mac and cheese, chicken nuggets, fries, or ketchup anywhere. You may ask, “How do they get the children to eat such things?” Picky American kids would, and do, turn their noses up at turnips and, dare I say it, salad, while French children learn to love them.

How French Children Eat

That brings me to Part Deux—how French children eat in that canteen. Again, Mr. Buford tells us:

“There they eat their food in silence. This is to encourage them to think about what they’re eating. They are served each course at a table by women who know how much the children want. They are not obliged to finish their food. But if they don’t, they don’t get the next course.”

Here I began picturing overfed American children throwing half their lunch in the trash, as if food is something to be disdained rather than appreciated. And why not? What is there to be appreciated about pizza, mac and cheese, and chicken nuggets with fries? How can ketchup stand up to a good, hand-made béchamel sauce? What is there to cherish about the same menu every week, featuring hamburgers, tacos, and American cheese?

Okay, I will admit I’m basing my opinion on what was served in my high school cafeteria. (The elementary school menu consisted of whatever Mom put in our lunchboxes. Ironically, that was at a parochial school called St. Louis de France.)

Perusing lunch menus posted online tells me that today’s school lunches are very different from when the Reagan Administration wanted to call ketchup a vegetable. Still, béchamel sauce, while not difficult to make, is creamy and white. There are a lot of American children who would scream at the very idea of putting a thick white sauce on anything.

What Teach Good Eating?

Now, some of you might be asking, “Why bother teaching good eating?” Here’s what Mr. Buford has to say: (NOTE: A brigade is the kitchen crew that works for the head chef. Daniel Boulud is a restaurateur and celebrity chef who was born in Lyon but works in the United States.)

“Daniel Boulud grew up on a farm, never ate in a restaurant, or bought food in a store until he was fourteen. But he had been thoroughly trained in French cuisine: by his farmer family, of course, but mainly by the school canteen. Every French member of the Mère Brazier brigade had grown up the same. The food our boys ate made them different from their parents.”

Different from any kid in America, too. I haven’t finished the book yet but I can only imagine what George and Frederick would say about the lunches offered in a typical American school cafeteria.

A Third Reason

So, there you have it. A third reason why French women don’t get fat. They begin learning to eat well when they are three years old. This appreciation for good food, carefully prepared, and eaten with respect, goes on for their school years. You don’t forget that kind of education.

PS: The book is wonderful. If you like literature about food, eating, history, French cuisine, the history of French cuisine, and what it’s like to move to France, read “Dirt.”