No matter how many times you have been in Boston, no matter how many streets you have walked down or which buildings you’ve looked at, you can still be surprised. Interesting things are tucked away down alleys, rising above eye level, glimpsed around corners, and appearing seemingly out of nowhere.

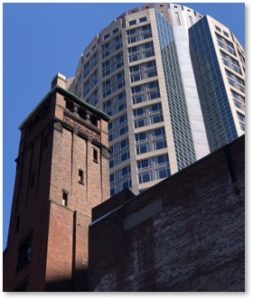

On Wednesday, we were driving down High Street in the Financial District when I looked up to see a red brick tower glowing against a deep blue sky.

On Wednesday, we were driving down High Street in the Financial District when I looked up to see a red brick tower glowing against a deep blue sky.

“Pull over,” I said. “I want to take some pictures of that.” About ten minutes later, I had the photos and a bad case of curiosity.

This building is labeled “The Chadwick Lead Works” both on the façade facing High Street and on the top of the tower. This site on the corner of High and Batterymarch Streets is a part of Boston that has suffered two major upheavals.

Two Upheavals

Fort Hill: Fort Hill, one of Boston’s original hills, held an elegant neighborhood in the 1790s and 1800s. From the leafy park at the top, residents could watch the ships sailing into and out of Boston Harbor. When fashionable neighborhoods moved to the South End and then the Back Bay in the 1860s, Fort Hill fell on hard times. Businesses moved in, absentee landlords rented crowded tenements and boarding houses to immigrants and Fort Hill became a squalid slum and the center of an 1849 cholera epidemic.

By 1872 the houses had been demolished, Fort Hill leveled, and its heavy clay used to underlie Atlantic Avenue. Now the towers of Philip Johnson’s International Place rise on its former location.

Great Fire: That same year, Hill was part of the 65 acres of Boston’s commercial district that burned to rubble in the Great Fire. The conflagration destroyed 776 buildings and caused $73.5 million in damage (equivalent to $1.411 billion in 2018.

The Chadwick Lead Works

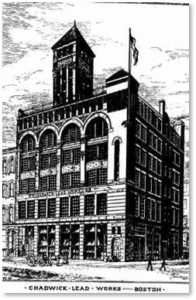

The building I spotted, the Chadwick Lead Works, went up in 1887. William G. Preston designed it in the Richardsonian Romanesque style and it flaunts many of the 19th century ornaments that gave buildings of the period such charm.

The base at street level is made of ironwork with the entrance and windows framed by pilasters of rusticated granite. The entrance is raised and deeply recessed into a timber-roofed “atrium” that also descends below street level. Box brick balconies project into this space from the second floor. A smaller granite string course separates the ground floor from the upper floors.

The second-floor brickwork alternates wide and narrow bands that frame the windows and act as pilasters between the second and third floors. A second granite string course underlies the building’s name, “Chadwick Lead Works” in deep terra cotta letters bracketed by dots and medallions. Businessmen of that era were proud of their accomplishments and often put their names front and center on their companies.

This building once contained all aspects of Joseph Chadwick’s industrial enterprise from fabrication to production. It served as the center of lead and hardware manufacturing and trade in Boston after the great fire.

Four Romanesque Arches

Four wide, round-headed arches divide the façade, rising from the second to the sixth floors. The brickwork above the third-floor windows bows out gently in rhythmic waves that force the windows to angle out. This makes the reflections of the rather bland International Place across the street seem to ripple in the glass, adding a sense of movement. Narrow granite columns divide the windows on the second and third floors while raised dots above the third-floor window decorate the brickwork between the carved sandstone capitals of the pilasters.

The capitals support the four arches as they, in turn, support the fifth-floor windows. It’s a harmonious composition that draws and holds the eye. Sixteen brick columns divide the windows on the top, or attic, floor. They flare out at the base, adding a final change of perspective, as the cornice projects out slightly from the façade.

Dragons and Ornaments

The building’s decorative theme seems to be stylized dragons. Three cast-iron dragons cling to the pilasters on the third floor and carved dragons occupy decorative panels at the base of the outer two pilasters. A carved and winged stone dragon’s head supports the corner flagpole.

Triangular terra-cotta panels decorate the space between he arches below the fifth floor. A triangular cap used to top the northeast corner above the flagpole, but that has disappeared. It echoed the top of the tower, which also bears the company name.

The Shot Tower

Invisible from the street in front of the entrance—and even from the alley to the north—is the tall tower that first drew my eye. It was neither ornamental, nor a statement of the owner’s ego. This being a lead works, this was a shot tower, built for a particular function.

NOTE: The best view of the tower is from the corner of High Street and Oliver Street.

A lead shot tower was once used in the production of small-diameter shot balls. Workmen dropped molten lead through a screen at the top of the tower. It free falls the height of the tower and is caught in a water basin at the bottom. (That is probably why the front steps go down to a lower level.) William Watts, a plumber in Bristol, UK, invented the process in 1783 to remove imperfections that caused muskets to misfire.

As the lead drops fall, surface tension pulls them into spheres. By the time they hit the water, they have started to solidify. The water catches without deforming the spheres and cools them the rest of the way. This process was less time-consuming and labor-intensive, and thus cheaper, than the old method of casting the shot.

Perfectly Spherical Shot

Shot towers thus cool molten lead in a way that create perfectly spherical lead shot in the most efficient and effective manner. The shot is primarily used in shotguns, and also for ballast, radiation shielding, and other applications in which small lead balls are useful.

This tower has narrow stepped windows, Pilasters that emerge from the brickwork and are capped with triangular capitals, Ionic stone columns, and carved stone blocks at the corners.

The Chadwick Lead Works manufactured lead products for many other applications, including lead pipe for the plumbing industry, as well as solder, fittings and connections. This is something of an homage, to the Mr. Watts, the plumber. Of course, no one back then understood the toxicity of lead or that it could leach into the water supply.

The shot tower must have once stood high above the other buildings constructed after the Great Fire. Now it’s almost invisible on the Boston skyline, dwarfed by the steel and glass commercial towers around it.

The Founder: Joseph H. Chadwick

The man behind the Chadwick Lead Works was Joseph Houghton Chadwick (1827 – 1892), the Lead King of Boston. He began working in a lead works as a child and in 1862 started a business of his own in Roxbury. He re-organized operations and moved the company to Boston in 1878.

Following the 1901 merger of the Chadwick Lead Works with the Boston Lead Company, operations moved to the corner of Franklin and Congress Streets and the building at 184 High Street fell into use as a warehouse.

A successful businessman, Joseph Houghton also served as a founding trustee of Boston University and served as president and as a trustee of Forest Hills Cemetery. He died in 1892 and was buried at Forest Hills.

If you have ever visited this garden cemetery, you have probably seen Mr. Chadwick’s mausoleum. Also designed by William G. Preston, it rises on Fountain Avenue overlooking Lake Hibiscus. The tomb, which is is built into the small sloped hill behind it., is an elegant church-like structure with a heavy grilled lead door bearing the name “Chadwick.”

Refurbished and Restored

In the early 1980s new owners refurbished and restored 184 High Street in accordance with National Park Service guidelines. They then re-positioned the old Chadwick Lead Works as one of Boston’s adaptive re-use office properties.

The Chadwick Lead Works

184 High Street, Boston MA