Becoming a manager is a lot like becoming a parent. It tends to happen quickly, often overnight. It opens up a world of new challenges, rewards, and opportunities but can be pretty scary, especially at the outset. And no matter how much advance time you have to prepare for the transition, you never feel quite ready.

Becoming a manager is a lot like becoming a parent. It tends to happen quickly, often overnight. It opens up a world of new challenges, rewards, and opportunities but can be pretty scary, especially at the outset. And no matter how much advance time you have to prepare for the transition, you never feel quite ready.

Becoming a manager is part of the career track in most corporate departments and organizations. The position conveys power and authority, delivers improved perks and benefits, results in a better salary, and sometimes even opens the door to a corner office.

To deserve all that, however, you have to become good at doing a number of things, from boring paperwork to arbitrating disputes among staff members and making the tough decisions, often under tight deadlines. No one is born knowing how to do this. Neither can one can learn it just by observing other managers in the office because much of what they do occurs behind closed doors or in meetings to which staff members are not invited. So how does a likely management candidate pick up the information needed to do the job?

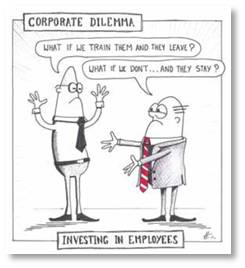

Management Training as an Investment

It used to be accomplished via management training courses or programs offered by the company as an investment in their best employees. These courses either took place onsite, given by the corporate training department, or offsite with consultants and specialists teaching the curriculum. Most companies offered both, depending on the subject matter.

When I worked at Data General, the initial management training courses, which were mandatory, focused on the day-to-day requirements of the job. These included hiring process, purchasing process, budgeting process, priority setting, balancing staff responsibilities, writing job descriptions and delivering performance reviews These were followed by courses that paid more attention to personnel management, motivation, and how to get the most from your team. The programs were held in-house and people paid attention because they wanted to get ahead. (Well, you also paid attention at Data General to avoid getting hit on the head.)

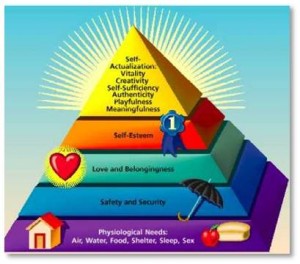

At Prime Computer, the management training included Management Development I, II, and III. These were given offsite—often at Twin Light Manor on the ocean in Gloucester, MA—and included a battery of personality tests as well as how Maslow’s Hierarchy applied to motivating staff members. I could only participate in MDI and MD II because MD III was limited to directors and above and I had not yet reached that level.

We had manuals to read, lectures to listen to, and role-playing sessions to participate in. Some attendees took these courses more seriously than others. I enjoy learning new things and wanted to get ahead so I studied. Of course, studying by the pool with a view of the ocean is no real hardship.

A Patriarchal System

That all stopped when I moved to Wang Laboratories because that company had no real management culture—and no training. All decisions went up the chain of authority until they reached an executive who would make the call—usually a vice president. This patriarchal approach meant that both managers and directors never really learned to handle the responsibilities that were part of their positions. The reality was brought home to me as a director when we started our budgeting process for the coming year. I received the mandate to increase budgets by 10 percent. So I called my staff of five managers together and told them to take their existing budgets, increase them by 10 percent, and then come to a meeting at the end of the week prepared to present how they had allocated the money and defend their decisions.

This seemed pretty simple to me. It’s something that any first-line manager at Prime could have done without breaking a sweat. Instead, however, two of my direct reports who were long-term Wang employees looked at me with furrowed brows and said they didn’t understand. I thought my charge to them had been pretty clear but I repeated it anyway with a little more description. Still, they didn’t understand what they needed to do.

This time I asked why and they explained that they had never had to do any budgeting—their boss had always done it for them and then just approved expenditures during the year. I was appalled. I told them to get their hands on that budget and start thinking but come to me if they had any questions. To their credit, the two men figured it out and we moved ahead.

But when Wang Labs tanked in 1989 and 1990, putting a lot of managers on the market, word got around pretty quickly that these folks couldn’t do the job despite their titles and salaries. I was actually told by one interviewer that they would only consider candidates who had been at Wang for two years or less for precisely this reason. Bad management has consequences.

Bad Management Decisions

This is what happens when companies don’t train managers how to do their jobs. And I’m not even talking about the blatant bad decisions, the employee churn, the waste of money, the poor products, and the bad publicity that often result. Neither am I addressing the blatant sexual harassment that has most recently tarred companies from Hooters to Yahoo and several Silicon Valley startups including Tinder.

There’s no question that companies run more smoothly and efficiently—not to mention with fewer lawsuits—if managers are trained to do their jobs well. Yet more and more big companies appear to be dispensing with this function as an unnecessary expense. Startups, of course, hire people who are supposed to know how to manage when they walk in the door. But if no one ever trains them, how can that happen?

Good management decisions come from people who are trained how to do the job. And, as I said in yesterday’s post on Employee Training, it’s the company’s responsibility to put the programs in place. No one else knows the culture, the goals, the focus, and the challenges as well as the company does. No government, school or candidate can do it for them.

Good management decisions come from people who are trained how to do the job. And, as I said in yesterday’s post on Employee Training, it’s the company’s responsibility to put the programs in place. No one else knows the culture, the goals, the focus, and the challenges as well as the company does. No government, school or candidate can do it for them.

So why do so many companies bail on this responsibility? There’s really only one answer: bad, short-sighted management decisions.