A shocking act of violence against tourists took place in Pakistan on June 22, when a group of gunmen invaded the base camp where an international team of climbers waited for a go at summiting Nanga Parbat.

Murder on Nanga Parbat

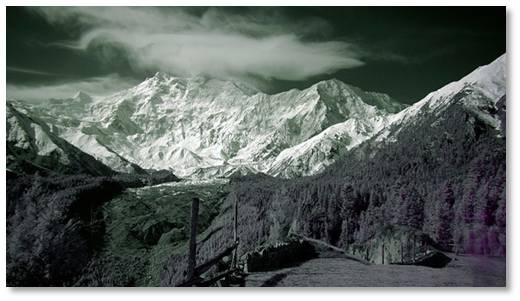

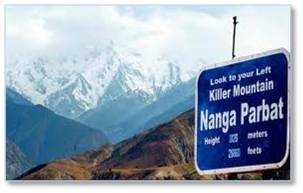

At 26,660 feet, Nanga Parbat is the ninth-tallest mountain in the world and a popular climbing destination even though it’s remote—located where the Karakoram and Himalaya ranges meet. The attackers, who had disguised themselves as Gilgit paramilitary officers, shouted in English that they were Taliban and Al Quaeda and the climbers should surrender.”

They proceeded to rob the mountaineers and their support staff, taking money and watches. The group then killed all but one of the foreigners—11 people in all. Although the attackers claimed to be exacting revenge for a drone strike in North Waziristan that killed Wali ur Rehman, a top Pakistani Taliban commander, that took place the previous month, the nationality of the victims did not matter. Only one was an American citizen and he had been born in China. The rest–two Chinese, three Ukrainians, two Slovaks, one Lithuanian, a Sherpa from Nepal—were gunned down along with a Pakistani cook whom the gunmen assumed was Shia.

Ordered Off the Mountain

The first report I read on this was on in The Wall Street Journal’s June 23 article: “Pakistani Militants Strike Climbers’ Camp, Killing 11” by Annabel Symington. In that report, Ms. Symington said that The Pakistani Taliban admitted that their splinter group, Janud Hafsa, had perpetrated the attack.

Five days later, Scott Rosenfield reported in Outside magazine that the Pakistani government had suspended all climbing licenses in the region and ordered all climbers off Nanga Parbat. More than 50 climbers who were on the mountain were asked to leave. This might not seem such a big deal but it dealt a devastating blow to the region’s economy. The Gilgit-Baltistan area of Pakistan does not have a thriving economy. The 15,000 to 20,000 adventure tourists who visit each year bring a lot of jobs and an influx of money to the area.

Taking Calculated Risks

Mountain climbers are by nature inclined to take calculated risks. They trust their lives to climbing partners, ropes, and technical gear. They confront altitude sickness, cerebral and pulmonary edema, falls and frostbite in parts of the world where doctors and emergency rooms may be days or weeks of travel away. Still, the decision on whether to climb or wait out a storm, to take one route instead of another, to push for the summit or retreat to base camp is theirs. They put their judgment, experience and skills against the weather and the mountain and try to come out of it successful–and alive.

Theft may also be part of the equation because the climbers are foreigners in distant places with bright clothing and expensive gear—a tempting target for impoverished villagers. But no one kills them. Why would they?

Inside the Murders with Outside Magazine

To answer that question, Outside this week went “Inside The Nanga Parbat Murders,” by David Roberts. Mr. Roberts explores the who and why of the killings, attributing them to Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), “a Sunni Muslim branch unaffiliated with the Afghan Taliban.” A spokesman reiterated that the motive was revenge for the death, by an American drone strike, of the group’s second-in-command, and that the action had been carried out by a splinter faction of the TTP called the Jundul Hafsa. With one stroke, aimed at the West, these terrorists have done more to damage the region’s economy than anything else could have. Mr. Roberts calls it a game-changer and one that will bring even more poverty to the locals.

With one stroke, aimed at the West, these terrorists have done more to damage the region’s economy than anything else could have. Mr. Roberts calls it a game-changer and one that will bring even more poverty to the locals.

The danger to climbers now comes not from the weather or the mountain—but from men with guns and the desire to use them. According to Mr. Roberts, “The impact on the Pakistan’s tourism business, on which thousands of merchants and porters depend for their livelihood, promises to be both profound and long-lasting.”

Instability Brings Poverty

Over the past decade, many climbers have avoided the region because of instability in Pakistan. But adventure tourism remains the economic lifeline in this remote area. In January, the region offered a 40% discount on climbing licenses and nearly 50 groups applied, up from 34 in 2012, said Yasir Hussain, deputy director of tourism in Gilgit-Baltistan. Three licenses were issued for Nanga Parbat.

A climbing license for Nanga Parbat ranges from $11,500 (unguided) to $14,500 (fully guided) and that’s just the start. There’s gear, travel, oxygen, supplies, and myriad other costs that I can only imagine. No one is going to risk that kind of investment—and their lives—in a place where random terrorists can walk into camp and shoot you. There are too many other mountains in the world to add that unnecessary risk to the ones that come with the climb.

Sending a Message

Both reporters interviewed Pakistani officials, who claim embarrassment and humiliation in the eyes of the world. The government of Nawaz Shareef is investigating. They have arrested four men and identified 16. The best thing the government can do now is send a message that killing adventure tourists is bad for the country and will not be tolerated. Anything less will encourage more violence and discourage further travel.

That will make things far worse for the people of the Gilgit-Baltistan region.