How did a Boston street named after a French nobleman’s estate turn into a center of vice and prostitution? It happened when urban renewal met the law of unintended consequences.

How did a Boston street named after a French nobleman’s estate turn into a center of vice and prostitution? It happened when urban renewal met the law of unintended consequences.

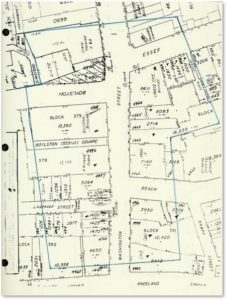

LaGrange Street runs from Tremont Street just opposite the Little Building and the Cutler Majestic Theater to Washington Street. It connects the 14th century to the 19th, the Theater District to Chinatown, and a former urban hotspot to rural France southeast of Paris. Phew! That’s a lot of heavy lifting for a one-way street that’s only a single block long.

The Story of LaGrange Street

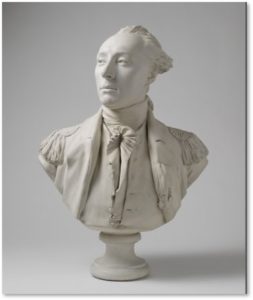

LaGrange street got its name in August of 1824 during the “farewell visit” of Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette. As a very young man, the French nobleman and General of the Continental Army contributed significantly to the success of the Revolutionary War by persuading his country to provide troops, ships and financial support.

He returned to America as a hero and “guest of the nation” at the formal invitation of the United States Congress for several months and was accorded many honors. According to the Massachusetts Historical Society:

Boston—all of Massachusetts—turned itself upside down to welcome Lafayette who had made only three brief visits to the city during and after the Revolution. Massachusetts matched or surpassed the welcome provided to the general elsewhere in the country, except in one respect: the densely-settled Commonwealth had no place that was unincorporated territory or not long-attached to its name that could become ‘Lafayette,” “Fayette,” or “Fayetteville”— new or renamed towns that sprang up wherever the general travelled. Fayette, in the former District of Maine, had been named for the general in 1795, and became part of the new state of Maine in 1820. Boston made do by renaming streets in honor of the general, La Fayette Avenue, and his country estate, La Grange Street.

The Chateau of LaGrange Bléneau

You will find that country estate, the Chateau de LaGrange-Bléneau, in the municipality of Courpalay, in the department of Seine-et-Marne in France. A stronghold of the 14th century it served as the seat of a domain, depending on the lordship of Melun. While the building dates from the 14th century, it was altered in the 17th century. The castle includes five circular towers from the 15th century and a chapel.

Ownership of LaGrange-Bléneau came to the Marquis de Lafayette through his wife, Adrienne d’Aguesseau, and he lived there from 1802 until his death in 1834.

In 1935, René de Chambrun, a direct descendant of Lafayette’s daughter, Virginie Lafayette de Lasteyrie, purchased the chateau. An international lawyer, he also served as president of Baccarat Crystal, manufacturers of fine crystal glassware. His mother was Clara Longworth, an American from Ohio, a Shakespeare scholar, and sister-in-law of Theodore Roosevelt’s oldest daughter, Alice Roosevelt Longworth.

The Foundation Josée and René de Chambrun, a charitable organization charged with preserving the structure, now owns the chateau and its historical contents. In 1942 the French Ministry of Culture listed it as a monument historique. The chateau has remained untouched since the death of the Marquis de Lafayette and is closed to the general public. No interior photography is permitted.

The Castle’s Hidden Archive

Yet, the chateau of LaGrange-Bléneau contains a tale to make any historian drool. Upon the 1955 death of his cousin, who held a lifelong residency, René de Chambrun discovered 14 walled-up attic rooms in the castle. They contained a large cache of documents, books, and letters: a family archive that went back to 1457.

The northwest tower held the Lafayette Library, which included the correspondence of the Marquis de Lafayette, some of which had never been opened. To get the full, amazing, story and see a photograph of that room, read this post on the Rodama Blog.

Death of Scollay Square

Now we return from the French countryside to 20th century Boston. The once-respectable LaGrange Street fell into disrepute in the 1970s with the coming of urban renewal. Boston’s post-World War II economic slump kicked off the decline of the lower Washington Street neighborhood. In the 20 years from 1950 to 1970, the city lost 200,000 people and investment virtually ceased. Lower Washington Street had been a center of nightlife for popular music where people attended some of Boston’s 50-plus legitimate theaters. During that decline, it turned into a dreary and dangerous locale in which only four theaters remained.

The coup de grace came in the early sixties when the city razed Scollay Square, with its burlesque houses, tattoo parlors, bars, vaudeville theaters, and seedy storefronts to create Government Center. The audience that had flocked to the the old Scollay Square moved to new businesses on Lower Washington Street that replaced those uprooted by eminent domain.

Lower Washington Street morphed into a red-light district that was grittier, tougher and more dangerous than Scollay Square. Vice, like many other services, is driven by supply and demand. As long as demand exists, supply will follow. And follow it did.

Birth of the Combat Zone

The Lower Washington Street area acquired the nickname of the “Combat Zone” because of frequent fights among biker gangs, soldiers and sailors on leave, and a new criminal element. Both Boston Police and Military Police officers patrolled it regularly.

The area grew even rougher in 1964 when the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA) tried to contain the vice in one area and designated two and half blocks of Lower Washington Street as an “Adult Entertainment District.” To survive, bars became striptease clubs. Storefronts turned into peep shows and X-rated bookstores. Entertainment grew even raunchier.

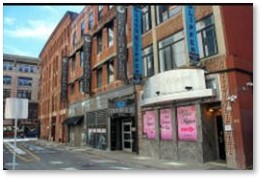

LaGrange Street sat at the heart of the Combat Zone. Boston’s street prostitutes “on the stroll” gathered there looking for business from college boys, military personnel on leave, conventioneers, and suburban family men. The johns walked from one strip club and bar to another or cruised down LaGrange Street in cars. Hookers went about their regular business but also stole wallets and rolled drunks. Scollay Square had never been this dangerous.

The Neighborhood Changes

The Combat Zone eventually fell to the Internet—a more efficient way to advertise and purchase vice and sex from pornography to “escort services.” As the seedy businesses closed, gritty old blocks fell and new structures were erected. Chinatown expanded into the Adult Entertainment District. New tenants provided the impetus for an upscale trend and the old Combat Zone began its comeback to decency and decorum.

LaGrange Street took the a big step in that direction in 1993 when Historic Boston, Inc. purchased and renovated the historic Hayden Building, one of only 10 commercial buildings designed by Henry Hobson Richardson, at the corner of Washington and LaGrange streets. Now a glossy, 21-story, luxury residential tower has risen at #47-55 LaGrange Street.

Developers describe their new structure as part of the theater district. You can bet that they would rather promote the part of LaGrange Street’s history that is connected to the chateau of LaGrange-Bléneau than to the old Combat Zone. It’s ever so much more tasteful.