My husband gave me an excellent book for Christmas. “The Truth About Baked Beans” has a somewhat tongue-in-cheek title but the subtitle, “An Edible History of New England” is more precise.

My husband gave me an excellent book for Christmas. “The Truth About Baked Beans” has a somewhat tongue-in-cheek title but the subtitle, “An Edible History of New England” is more precise.

Written by Meg Muckenhoupt, the book, “…explores New England’s culinary myths and reality through some of the region’s most famous foods: baked beans, browned breads, clams, cod and lobster, maple syrup, pies, and Yankee roast.”

When I first looked over the synopsis, I wondered about the “myths” part and looked forward to finding out. After just the first chapter, though, I find myself wondering about a missing cuisine.

Who Is a Yankee?

The first chapter, “Who Is a Yankee?” details who actually is a New Englander. We know about the Puritan Protestants, of course. They came from southern England, particularly around Lincolnshire north of London. The Puritans brought their own stores and diet when they settled among the Native tribes of Wampanoag Indians. The Native Tribes contributed ingredients like squash and beans but cooked their food in ways different from those of the Europeans.

The melting pot warmed up pretty quickly, though, with waves of migration adding new residents across the six states. The author discusses how the largest and oldest groups of immigrants added their own culinary specialties to our regional cuisine:

- The Irish

- The French Canadians

- The African Americans

- The Italians

- The Poles

- The Portuguese

- The Greeks

- The Chinese

- The Puerto Ricans

What Did the Immigrants Eat?

Each group brought its own approach to cooking, with recipes, ingredients, and diets from their own “old country.” This should come as no surprise to any of us. It explains why Boston residents today go to Chinatown for Chinese food, the North End for Italian cuisine, Cambridge for Portuguese specialties, and Southie for Irish cooking, among others.

While these neighborhoods may concentrate restaurants serving regional cuisine, however, we can actually find them all over the city. Greek pizza with its signature crunchy fried bottom, Southern barbecue, Chinese take-out places, and Irish pubs have spread all over the greater Boston area.

The French Canadian Exception

One exception does stand out from the above list, however. Where are the French Canadian restaurants? What Boston neighborhood serves classic tourtière pork pie at Christmas when Italians observe the Feast of Seven Fishes?

You can order the buckwheat pancakes called ployes at the Deluxe Town Diner in Watertown but that’s all. If you want tarte au sucre, salmon pie, pate Chinoise, boudin noir, yellow split-pea soup, or cretons anywhere in Boston, good luck.

The Big Question

My question, of course, is why? Ms. Muckenhoupt says, “French Canadian American cuisine, like Irish American cuisine, is not celebrated much in New England, apart from occasional articles on tourtière (meat pies) at Christmas.”

But while many Bostonians eat corned beef and cabbage with Irish soda bread around St. Patrick’s Day, far fewer have even heard of French Canadian specialties. The author does not give a reason.

Other immigrant groups established businesses and made money selling their own regional cuisines to curious and adventurous diners, so why didn’t the French Canadians do the same thing?

They operated boarding houses that served food to boarders, so opening a restaurant would seem a logical extension. Instead, my ancestors seem to have adopted a more traditionally Yankee diet for their customers.

The Fall River Connection

I grew up in Somerset, MA, across the Taunton River from Fall River amid a strong French-Canadian culture. In Chapter One I learned that:

“In 1900, Fall River, Massachusetts, with 33,000 French Canadian residents, was the third largest community of Francophones in North America after Montreal and Quebec City.”

Our family attended St. Louis de France Church in Swansea and I went to both St. Roch’s School in Fall River as well as the St. Louis de France parochial school.

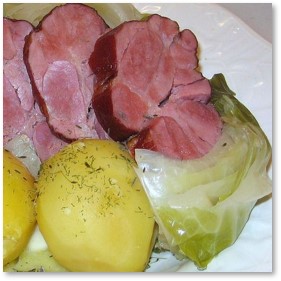

Mom made tourtière pie not just at Christmas but throughout the year and it was a Saturday night favorite. We balked at boudin noir, although both parents consumed this blood sausage with relish.

The four of us kids also enjoyed her salmon pie, but she refused to make cretons because she thought this coarse paté was too fatty. Heart disease runs in Dad’s family and she wasn’t about to encourage that. Our boiled dinners used Daisy ham instead of corned beef.

While Mom didn’t bake traditional date squares, amazing raisin squares came out of her kitchen. They were enjoyed at church suppers and went quickly at bake sales. I contribute her meatball stew to our church’s Harvest Fair where it sells out regularly. She made her own baked beans in a classic beanpot.

A Lack of French Canadian Chefs

I suspect the lack of French Canadian cuisine in the Boston area is due to the fact that these immigrants gravitated to mill towns like Fall River, Lawrence and Lowell in Massachusetts, Manchester, NH, and Woonsocket RI. That meant Boston never had a strong French Canadian neighborhood — but it did have a persistent anti-Catholic bias.

Did it have to do with how the French Canadians preferred settling in “petits Canadas” rather than assimilating? Or does the explanation come with French Chefs who trained in France rather than Quebec City or Montreal?

Whatever the cause, I do know that these dishes deserve better than to disappear, overwhelmed by America’s great melting pot of burgers, pizza, fries, and spaghetti.

If you go to Fall River, you can find some French Canadian dishes for sale in restaurants and bakeries, but you have to look. St. Anne’s Shrine held a tourtière pie sale earlier this month, for example. Failing that, just make them yourself. It’s not difficult.

Unless some enterprising French Canadian chef decides to come down from Quebec City to open a restaurant here.

PS: We’re having leftover tourtière pie for dinner tonight. (I put a clove of garlic in mine.)