This post on the Ayer Mansion is number 13 in my series on Boston’s Hidden Gems. A list of previous posts appears at the bottom of this page.

Q: What do you do if your heart calls you to the stage but you live in a time when no woman of good character could possibly become a professional actress?

A: You build a house with your own private stage in the lobby.

The Ayer Mansion

Such a house exists in Boston and what a stage it is!

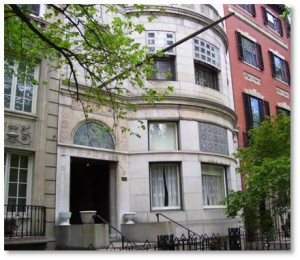

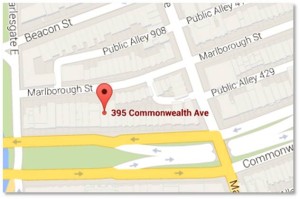

The Ayer Mansion at 395 Commonwealth Avenue is on the block just west of Massachusetts Avenue, which technically places it in the West Bay, rather than the Back Bay. It is, however, included among Back Bay houses because it is both historically notable and artistically spectacular.

The house was designed by Architect A.J. Manning in collaboration with Louis Comfort Tiffany, who created both exterior and interior art work.

The Ayer Mansion’s Four Distinctions

The Ayer Mansion is:

- The sole example of a house designed from its inception by Louis Comfort Tiffany.

- The only surviving house over which Mr. Tiffany had complete control, which allowed him to integrate themes and details both inside and outside.

- The only private home with a Moorish theme in the Back Bay.

- The only place that has in situ interior and exterior components designed by Tiffany.

When construction began on the mansion in 1895, however, it was seen as an outlier, an anomaly, and almost an intruder. The house, built for textile magnate Frederick Ayer, was made of white limestone and granite instead of the Back Bay’s ubiquitous red brick. It had Oriental themes and was too far west to be fashionable. Frederick Ayer lived in Lowell and his second wife Ellen Barrows Banning Ayer was from (gasp) St. Paul, Minnesota.

The Out Crowd

Mrs. Ayer was a “theater buff” who loved travel, the stage and bustle of the city. An amateur actress, she was involved with local theater and was a “diseuse” who performed monologues. Mr. Ayer began courting her by taking her (chaperoned) to see Edwin Booth in “Hamlet.”

As outsiders, non-Brahmins, and not part of Boston’s insular social group, the Ayers were never going to fit in to the city’s tight-knit web of “good families” with their network of what William Dean Howells dubbed “cousinships.”

Embracing their out-crowd status, they decided to build something very different. Given the cautious, conservative approach of most Bostonians, this was not difficult to do. The Ayers certainly succeeded in shocking their more reserved contemporaries–and neighbors–with a house that looked like nothing else in Boston.

Historical Note: Frederick and Ellen Ayers had three children. Their daughter, Beatrice Banning Ayer, married George Smith Patton, Jr. in 1910. He was a lieutenant in the United States Army who rose to the rank of General in World War II.

Mrs. Ayer’s Stage

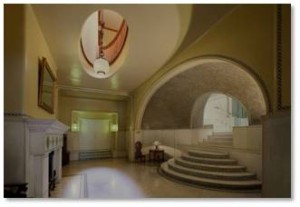

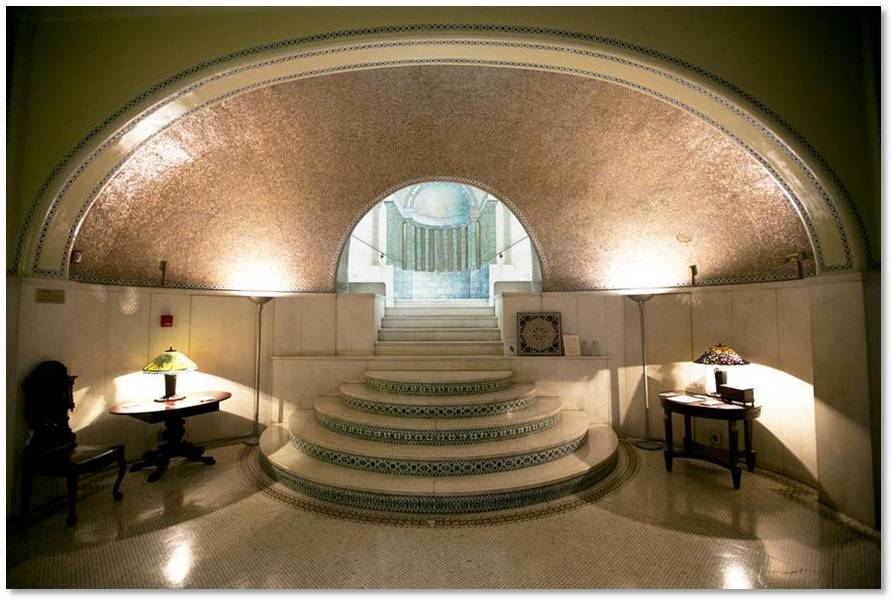

In planning the mansion, Mrs. Ayer made sure she had a stage of her own to tread. This astonishing work of art is located just inside the lobby to the right. It includes a proscenium arch lit by electric bulbs, hidden doors on each side for entrances and exits, and five semi-circular stairs leading to five narrower straight stairs.

At the top is the piece de resistance. In structure, it’s just a landing with stairs leading to left and right from either side and a flat back wall.

You would never think it’s flat, however, because that wall holds a true hidden gem: a trompe l’oeil glass mosaic mural of a classical temple that creates the illusion of space and light where none exists. It’s made of opalescent glass—semi-transparent glass that is backed by metallic foil—and “plated” surfaces that layer clear and opaque glasses to add depth of color and create the perception of three dimensions.

No piece of the mural projects or recedes more than a half inch, yet the viewer is led to think she can walk straight ahead into a columned and domed temple. The adjoining marble engaged columns, raised on a slightly projecting plane, further add to an optical illusion so complete that it is almost impossible to stand before it and believe that the space does not exist.

Tiffany Touches

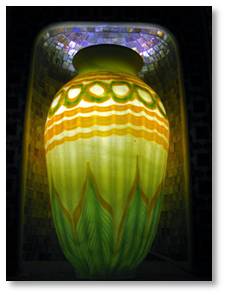

The rest of the Ayer Mansion is replete with other L.C. Tiffany touches from lamps to light sconces and a globular chandelier, from intricate woodwork to the back-lit glass mosaic ceiling over the staircase. The mansion’s interior holds a treasure trove of Tiffany glass and the exterior sports mosaic panels on the balcony and a glass mosaic fanlight over the front door.

Artistic Note: Ellen Banning Ayer was a descendant of Captain Frans Banning-Coq, the gentleman in the yellow suit who appears in the foreground of Rembrandt’s famous painting familiarly known as “The Nightwatch.”

Directions to the Ayer Mansion

Anyone who loves Tiffany glass, integrated art and architecture, or just a beautiful house, should tour the Ayer Mansion. It was named a National Historic Landmark in 2005.

All of my Hidden Gems are available to the public and this is no exception. Although the Ayer Mansion is currently owned by the Catholic Church, which uses it as the Bayridge Residence and Cultural Center for female college students, tours are available at least twice a month on Saturday and Wednesday. Reservations are required. A donation of $10 per adult is requested to help with the costs of preserving and restoring the house.

Today’s residents include theatrical young women who act out skits on Mrs. Ayer’s beautiful stage. The acoustics are said to be excellent.

The Ayer Mansion is located on the north side of Commonwealth Avenue, just west of Massachusetts Avenue. Street parking is limited buy you can put your car in the Prudential Center garage and walk over. With public transportation, take the T’s Green Line to the Hynes Convention Center stop and walk west or to the Kenmore stop and walk east.