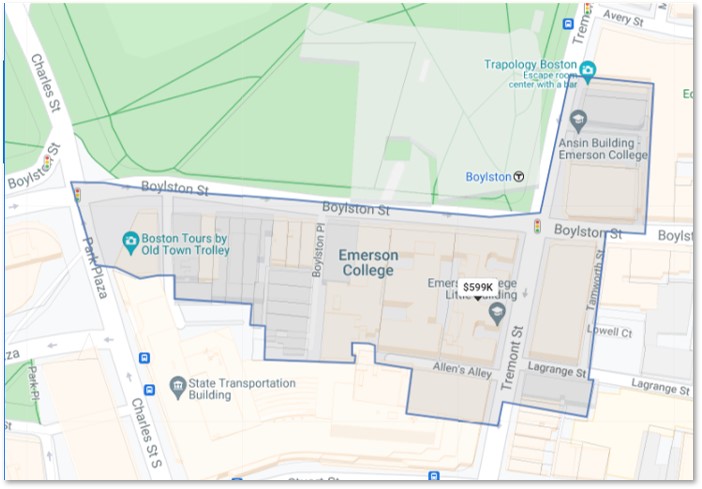

The two blocks of Boylston Street from Charles Street to Tremont Street—and up Tremont Street to Avery Street—are known as Piano Row, part of Boston’s Theater District. The area received this name because of the concentration of piano showrooms and music-related businesses that once occupied these shops and offices.

While Piano Row’s heyday ran from 1890 to 1930, its musical heritage lasted well into the twentieth century. I remember when this block was filled with music stores and its shop windows showcased gleaming upright and grand pianos.

The Golden Age of Pianos

In the nineteenth century, the manufacture of shoes, fabrics and pianos led Boston’s industrial growth. Companies took advantage of the skilled craftsmen and carpenters who had immigrated to the city from Europe. No fewer than 10 piano manufacturers could be found in the Boston area.

With no radio or television, no records or DVDs, no smartphones or playlists, pianos brought music into the home. Well-bred young ladies learned to play as part of their educations to entertain family and guests. During this “Golden Age,” pianos were highly desired musical instruments and were usually the big-ticket item in a household budget. Pianos also were essential investments for pubs, bars, music halls, and silent-movie theaters.

The Musical Shops of Piano Row

At one time, Boston’s Piano Row included:

- #100: The Wurlitzer Company

- #114: The Pond Piano Company

- #146: The Mason and Hamlin Piano Company (demolished)

- #154-156: The E.A. Starck Piano Company

- #158-160: Vose and Sons Piano Company

- #162: Steinway and Sons Pianos

These short blocks formed a showroom for the musical instruments produced the piano factories of the South End. Now it’s a different story, however. Three things ended the Golden Age of pianos:

- The Great Depression, when jobs disappeared, and disposable income shrank,

- World War II, when manufacturing converted to producing war materials,

- The rise of the automobile, which became the new big-ticket household item.

That meant both the supply and demand shrank in a short period of time. Back then, pianos were a good investment that could be re-sold for more than the purchase price. Today, pianos have become a financial liability that people pay to have removed.

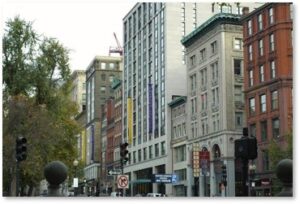

Commercial Buildings

While the showrooms are gone and the shop windows empty, Piano Row still holds several high-quality commercial buildings that don’t get the architectural respect they deserve.

Emerson College owns most of Piano Row and its storefronts. One entire building has disappeared, however, replaced by an anonymous modern structure.

I have written about parts of Piano Row before. In this post, I originally intended to cover it all its buildings, starting at Tremont Street. As is often the case, however, I uncovered too much material to cram into just one post. Instead, I will discuss just two buildings today and finish up (I hope) next week.

The Little Building

80 Boylston Street

Clarence Blackall

1917

I have written two posts about the Little Building, which was built as a commercial office building and is now an Emerson College dormitory known as LB. You can read more about this interesting structure in these two posts:

The Colonial Building

Clarence Blackall

106 Boylston Street

1889 – 1900

This large building combines the Emerson Colonial Theater with several store-front spaces. An innovative design, it made the best use of prime street-level frontage while providing revenue for the theater.

To the left of the entrance is the Art Deco-ish façade of the Emerson College Print Copy Center, while an empty storefront that appears to have fallen victim to the Covid-19 lockdown is on the right. Although the print center proclaims, “We’re Back,” I didn’t see any evidence of this and the building’s sign has been removed.

I like the look of the copy center’s storefront with a bronze frieze and mock fanlight that contrast with the black marble around it. Floral medallions decorate each corner at the top and a “keystone” with carved face holds the center. This shop front has style and says, “Notice me.” You bet.

The 10-story brick building itself gets little attention architecturally. (Neither it nor the Little Building warrant a mention in the “AIA Guide to Boston.”) Go figure.

Its granite façade features carvings around the arched main door, and a dentil course at the second floor above the building’s carved name. Seven Corinthian columns separate a row of ten balconies at the ninth floor. The arched main entrance has ornamental carvings around and above the door. The Colonial Building may not be spectacular, but it is well worth a second look.

The Emerson Colonial Theater

Clarence Blackall

1889 – 1900

Originally just the Colonial Theater, this is the oldest continually operating theater under its original name in Boston. Designed by Boston’s most prolific theater architect, it was financed by Frederick Lothrop Ames, Jr.. As a center for theatrical debuts, it played host to most of the major actors, actresses, directors, choreographers, etc. before a play hit Broadway.

On the outside, the Emerson Colonial looks like a small boutique theater. From the street you see only a simple marquee bracketed by two gilt-framed poster frames. The inside, however, is large and spectacular. To give you an idea, it opened on December 20, 1900 with a performance of “Ben-Hur” that featured eight live horses running at a gallop on a treadmill. That amazing piece of stage equipment is still in the theater.

The Emerson Colonial Theater’s elaborate gilded interior feature Baroque wood carvings and bas-reliefs by the John Evans Company with murals on the walls and ceiling.

While the theater remained closed as of July 10, you can get more information and see some photos in this blog post:

- The Emerson Colonial Theater: Gilded Glory Returns

- #mycolonial: Video History of the Colonial Theater

To see what the theater looks like inside, watch this short video clip that I took during a tour of the theater after its multi-million-dollar renovation.

End of Piano Row: Part 1

That takes us to the Walker Building. We’ll stop here this week and pick up the rest of the block going down to Carver Street next week.

Hello Aline,

I came across your blog post while researching the origins of my 1901-ish Henry F. Miller piano. I found a print ad online referencing a “wareroom” location at 88 Boylston Street, Boston. Do you happen to know anything about the company, the building and whether or not it still stands? Thank you for your interesting post!

Eileen: Unfortunately, I’m not an expert on Boston’s piano industry. I do know that there were multiple piano factories in the city, primarily in the South End. In fact, the presence of those factories were a factor in driving well-to-do residents into the New Land, or Back Bay.

A wareroom is a showroom, a space in which goods, or wares, are exhibited for sale. As to whether #88 Boylston Street still exists, check out my whole series on Piano Row. I described every building along that block, which is where #88 would be located. If I didn’t write about it, the building is not there. For more information on your Henry Miller piano, you can try a reference librarian at the Boston Public Library’s central branch in Copley Square. You can also ask Anthony Sammarco, who has written extensively about the city and might know more than I. You can reach him through his Facebook page. Good luck with your search. I’d love to know if you find answers to your questions.

Love this! I’ve been looking into one of the music sellers who traded from Colonial Building.

Do you know how/why the building got its name?

Karen: I don’t know specifically but the two buildings were constructed at the same time, possibly by the same person. One likely took its name from the other. Thanks for your question.

I remember, as my mother was an interior decorator, perusing the showrooms in The LIttle Building. It was an enchanting place to wander and shop.

I miss Boston the way it was.

Bailey’s Ice Cream Parlor was diagonally across the street and we would go there for an ice cream sundae which would be dripping over the sides of the dish with hot fudge sauce and marshmallow!