2017 is the year of the chipmunk.

2017 is the year of the chipmunk.

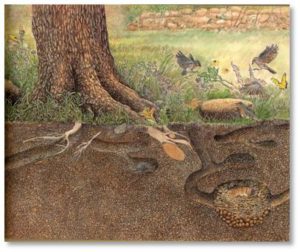

If you live anywhere outside a city in New England you have noticed the incredible number of chipmunks this year anywhere you look. The Eastern Chipmunk (tamias striatus) appears to be in the second year of a population boom that was kicked off by oak trees in 2015.

The Chipmunk Population

I can sit on my deck and watch these little creatures zipping hither and yon. They like to race across the stone wall between my back yard and the golf course next door. Zip, zip, zip. It’s like watching particles inside the Large Hadron Collider, except that they go in both directions and never collide.

They also make their signature “Chip, chip, chip” call continuously. All. Day. Long.

Chipmunks have taken over the berm atop the retaining wall and, I suspect, have built an entire city beneath it. Where once I found two or three chipmunk holes, now they are everywhere. Chipmunks have eaten the roots of a big hosta in my perennial garden, turning it into a sad, wilted ghost of its former glory. I would put out Moletox but I’m afraid Mystique would catch and eat one of the critters and poison herself.

So many chipmunks are running around this year, however, that even Mystique, the great chipmunk hunter, seems to have given up. Yesterday she was sitting on my lap on the deck and we both kept hearing strange noises from under the grille cover. Then, as we watched, a chipmunk came out, looked up and saw us, and zipped under the grille again. Mystique checked out the furry invader of her turf—and then went back to sleep.

A Mast Year

The reason for this population explosion goes back to 2015, which was a “mast year,” one in which oak trees produce an enormous number of acorns. For reasons unknown to modern science, oak trees simultaneously drop a much larger volume of acorns every two to five years.

The reason for this population explosion goes back to 2015, which was a “mast year,” one in which oak trees produce an enormous number of acorns. For reasons unknown to modern science, oak trees simultaneously drop a much larger volume of acorns every two to five years.

I think the best theory is that overproduction of acorns gives the trees a greater chance of reproducing because the acorn-eating critters like squirrels, wild turkeys, deer, bear, and chipmunks can’t eat them all. More acorns means better odds that some acorns will survive and germinate.

How do the oak trees know when to rev up production? That’s a mystery, too. But there’s no doubt that they synchronize and do it all at the same time.

What is Mast?

Why is it called a “mast year?” Mast is the fruit of trees like oak, hickory and beech or of woody shrubs. It includes nuts and acorns and makes a good source of food for free-range pigs as well as wild critters. In a mast year, a large oak can drop up to 10,000 acorns, fortunately not all at once, and you can find up to 100 acorns per square meter of land under oak trees.

You know it’s a mast year when you hear acorns whacking on your roof, bouncing off the car in the driveway, and even hitting you in the head. Doing yard work or hiking can feel like skating around on marbles.

You know it’s a mast year when you hear acorns whacking on your roof, bouncing off the car in the driveway, and even hitting you in the head. Doing yard work or hiking can feel like skating around on marbles.

In our old house I would scoop mast-year acorns into buckets and drop them into the pond for the ducks and geese—which flocked to the feast. I could fill up a five-gallon plastic bucket in minutes and go back for more. That was from just one tree.

Abundance Leads to Abundance

In a year of abundant food, the wild critters that eat the nuts and acorns also reproduce in greater numbers, creating a “mast boom” of new babies. A winter cache of acorns means that rodents can get a head start on the breeding season. Female chippies can thus deliver two litters instead of just one for the year, resulting in double the chipmunks.

This happened in 2015. The population increase continued in 2016 as well, aided by last year’s mild winter and low snow pack. Contrary to country “wisdom,” a mast year does not predict a hard winter.

This happened in 2015. The population increase continued in 2016 as well, aided by last year’s mild winter and low snow pack. Contrary to country “wisdom,” a mast year does not predict a hard winter.

The chipmunks also play a role in the life cycle of other animals by providing them with easy pickings: More chipmunks means more food for predators. Twice this summer I have seen a coyote trotting along the berm behind my deck. He or she goes where the food is. Maybe that’s why Mystique is staying close to the house.

A Bad Year for Ticks

Abundance also means that other acorn-eating birds and animals can reproduce in greater quantities. One of these is the white-footed mouse, which plays a critical role in the life cycle of the black-legged tick that carries Lyme disease, Babesiosis, and Anaplasmosis. More acorns = more mice = more ticks = more incidences of tick-borne diseases. These diseases peak two years after a mast year and that means now. The ticks will be particularly prolific in the fall.

The whole cycle will repeat itself. This fall will make two years from the last mast year and we probably won’t see another over-production for at least another year or so. The severity of this winter will have an impact on animal populations next year.

In the meantime, though, take strong precautions when going into woods, meadows, weedy areas, gardens and other places where ticks hang out. That’s one reason I’m staying close to the house this summer. I’ve had Lyme disease and don’t want to get it again.

Mystique and me watching the chipmunks. Zip, zip, zip.