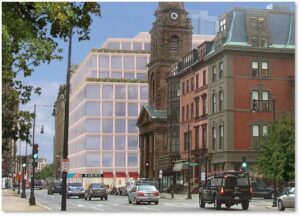

The Arlington Building : Courtesy of the Boston Herald

When it comes to the demolition of the Arlington Building at 350 Boylston Street, the optics are not good. Of course, the optics have been terrible for the last 14 years.

The Arlington Building anchors one end of the block between Arlington and Berkeley Streets on the south side. That block on that side of the street has been an eyesore—deliberately created by its two owners—for many years.

While the north side of the street prospered and bustled, the south side looked like a retail block in the Rust Belt. Empty storefronts covered dilapidated old brownstone buildings and Going Out of Business signs warned of an ongoing imminent demise that never seemed to happen.

Hoping for Better Times

We all looked forward to a time when developer Ron Druker would clean up his act and improve this gateway to the Back Bay’s largest and most vibrant street.

We did not imagine this.

The Arlington Building wrapped

Right now, the block looks like one of the late artist Christo’s sculptures, braced as it is in scaffolding and draped in white plastic. Behind that covering, the heavy machinery will move in to demolish three buildings.

In their place, Mr. Druker will construct a building so out of place with its surroundings, it amazes me that it passed the Back Bay’s stringent architectural guidelines. The historic Arlington Street Church with its 16 Tiffany stained-glass windows will face something that looks like it drifted over from the Seaport.

The new 350 Boylston Street will be a 9-story mixed-use development designed by Robert A.M. Stern Associates (RAMSA) that combines office and retail uses. It will include a below-grade parking garage for approximately 150 vehicles. Presumably, the contractors will excavate this from the Back Bay’s underlying gravel fill without encountering the same problems experienced by Architect Henry Cobb with the Hancock Tower. I hope the Arlington Street Church protects its windows during construction, though.

Architectural rendering of the new 350 Boylston Street

The Arlington Building

The most important of the three buildings up for demolition is the Arlington Building on the corner of Boylston and Arlington Streets.

Built in 1904 and designed in the Beaux-Arts style by Boston architect William T. Aldrich, the Arlington Building was built as part of a row in 1904. It began as a branch of the Bryant and Stratton Commercial School, which requested the building’s large windows. At the time, Arlington Street ended at Boylston Street, blocked by the Boston & Providence railroad terminal to the south.

The city cut Arlington Street through in 1904, which anchored the building at its end of the block. Art Deco details were added in 1929.

Made of light gray brick and granite, the exterior features beautiful foliate carvings on string courses. A dentil string course separates the second and third floors, marking the line between retail and office space. A copper chenéau, or ornamented crest, crowns the roofline.

The roofline with copper cheneau

Shreve, Crump and Low

The Arlington Building is better known to Bostonians as the long-time site of Shreve, Crump & Low, the premiere jewelry store that has operated in Boston since 1726. The business occupied the Arlington Building’s first two floors for 77 years.

The Gurgling Cod

You go to Shreve’s for that special gift, a piece of “important” jewelry, as well as silver, antiques, porcelain, and artwork.

Generations of Bostonians went to Shreve’s for the quirky, but classic, Gurgling Cod pitcher.

Major League Baseball went to Shreve’s for the Cy Young Award trophy.

The International Tennis Federation went to Shreve’s for the Davis Cup trophy.

Ron Druker went to Shreve’s so he could demolish its historic building and erect a modern structure that fits into the Back Bay not at all.

Women’s Industrial Union

The Women’s Industrial Union Building will also fall to the wrecker’s ball. Although it has been closed for many years, I remember that lovely, elegant space with the gilded swan hanging outside. When I was in college, I used to shop there for Christmas gifts I could afford.

The brownstone next to it makes up the trio scheduled for demolition.

The White Glass Box

Mr. Druker has had permits to develop this site since 2008 but he allowed the three buildings to deteriorate while he searched for just the right office tenant. He kept the three buildings mostly vacant for 14 years because he designated them as development sites.

Now he’s ready to drop onto Boylston Street a glass box that looks like nothing else around it. Imagine a piece of the Seaport gleaming in between the sedate brownstone church and the brick Four Seasons Hotel (which Mr. Druker also owns), and kitty-corner from the Public Garden.

The problem does not lie with the building’s design. It would look perfectly fine in the Seaport or Kendall Square or a suburban office complex. It just doesn’t belong here.

Unhappy Bostonians

The view from Arlington Street

People are not happy about this development. Granted, Boylston Street holds a polyglot collection of architectural styles as it stretches through the Back Bay. It goes from the Arlington Street Church’s Georgian and Italianate lines at the east end to the modern Hynes Convention Center at the west with two wildly different Philip Johnson buildings in between. You can throw in Frank Gehry’s Tower Records on Massachusetts Avenue for good measure.

Still, this corner has an importance all its own. With the stately church across the street and Boston’s hallowed Public Garden on the opposite corner, the site deserves something better than this.

The Arlington Building is not going down without a fight. For all the details on the struggle to preserve it, read this post from the Boston Preservation Alliance.

Seeking Consistency

I’m not someone who laments change or preserves a decrepit building just because it’s old. Once you have seen the wildly innovative structures going up in Amsterdam, you can’t go back to red brick or Brutalist concrete. And I can’t criticize reflective glass walls in the Back Bay because the Hancock Tower got there first.

Dentils and stone carving

Still, it would have been nice to know that, if we couldn’t save a building that holds so many memories for so many Bostonians, its owner could at least replace it with something more consistent with its neighborhood. Perhaps, even, something that retains some components of the old building. I hate to think of those oak-leaf carvings getting dumped into a landfill somewhere.

Adaptive reuse? Facadism? Whatever it takes. Both of those could work.

So could a lot more imagination and respect for the location from RAMSA and Ron Druker. Boston has demolished historic buildings—heck, whole neighborhoods—before in the name of progress, modernization, and increased tax revenue. One would think we would have learned better by now.