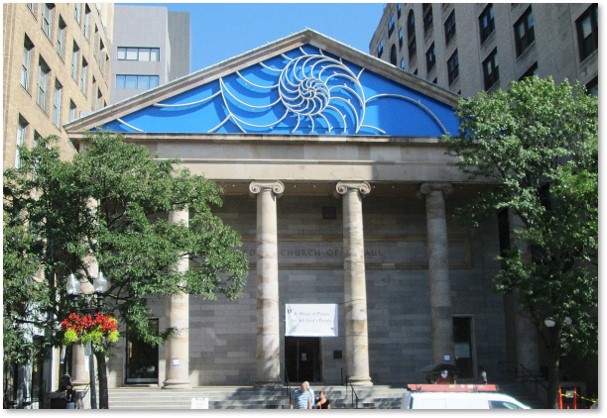

When I first came to Boston, I would pass by a plain Greek temple on Tremont Street and wonder what it was doing there. Probably because it was a church, St. Paul’s reminded me of the ancient temples in Europe that had been re-purposed as Catholic churches. Unlike Rome, however, this building seemed out of place amid the tall 20th-century department stores and office buildings that surround it.

The story behind the Cathedral Church of St. Paul may not go back to antiquity like those European temples, but it does speak to Boston history. It even bears historical connections to England, Quincy Market and King’s Chapel a few blocks away.

The Architecture of Classical Greece

The Cathedral Church of St. Paul, Boston is the historic cathedral church of the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts. Located on Tremont Street, it was built on land originally owned by John Wampas, the Indian, in 1666-1667.

St Paul’s looks out on Boston Common and the Park Street T station. Alexander Parris and Solomon Willard created the structure in 1819, bringing the architecture of classical Greece to a city notable for its Georgian and Federal buildings. Parris worked on St. Paul’s five years before he created Quincy Market and may have used one to inspire the other. Despite their completely different functions, both structures were constructed of granite and have classical temple façades.

First Greek Revival Church

Mr. Willard went on to create the Bunker Hill Monument, an Egyptian-revival obelisk.

St, Paul’s Church, once the largest structure in its Tremont Street neighborhood, became the first building with Greek Revival architecture in Boston and was the first Greek Revival church in New England.

At the time, Boston had two other Episcopal parishes in Boston, Christ Church (better known as Old North Church) in the North End, and Trinity Church in the Back Bay. Both had been founded before the American Revolution as part of the Church of England.

The founders of St. Paul’s wanted to create a totally American parish in Boston. I find this ironic because the stones that form the exterior of St. Paul’s come from St Paul’s Cathedral in London and St. Botolph’s Church in Boston, England.

St. Paul’s Empty Pediment

The church’s classical Greek portico has six ionic columns of Potomac sandstone that hold up a pediment over a recessed porch. The original design called for the triangular pediment to hold a bas-relief sculpture of St. Paul preaching before the Emperor Agrippa II, which Mr. Willard had planned to carve. As with the missing steeple of King’s Chapel, however, funds ran out before the sculpture was begun.

The cost of building St. Paul’s had more than doubled over the estimates. This proved to be a problem, even for the church’s wealthy Beacon Hill parishioners. I struggle to imagine that men like Harrison Gray Otis, David Sears, and William Appleton would have been unable (or unwilling) to contribute more. Nevertheless…

Two of St. Paul’s senior wardens, Daniel Webster and Dr. John Collins Warren, finally shepherded the building to completion. Nevertheless, the pediment, which measures 75 feet wide and 16 feet high at its apex, remained empty of its eponymous saint.

When I first saw the church from Boston Common in the sixties. I thought that it looked decrepit. Between the old English stones, years of accumulated city grime, and the rough blocky pediment, it did not present an attractive appearance. The unfinished façade remained for 194 years until 2013.

The Pediment: Welcoming

“Build thee more stately mansions, O my soul,

As the swift seasons roll!

Leave thy low-vaulted past!

Let each new temple, nobler than the last,

Shut thee from heaven with a dome more vast,

Till thou at length art free,

Leaving thine outgrown shell by life’s unresting sea!”

Then a large sculpture entitled “Ship of Pearl” by Donald Lipski rose into its current position in front of a bright blue backdrop. This crosscut view of a chambered nautilus with its shell spiraling outward was crafted from hand-formed aluminum. Weighing 650 pounds, its curving shapes fill the triangular space while it is so graceful and linear as to appear weightless.

Sculptor Donald Lipski found inspiration in the above lines of a poem, “The Chambered Nautilus,” written by Oliver Wendell Holmes in 1858, when the church was relatively new. Mr. Lipski wanted his design to be “spiritual in nature yet not narrowly or specifically Christian, in keeping with the church’s all-inclusive mission.”

“Ship of Pearl” stands away from the pediment’s face, which adds interesting shadows and colors to the background. Lit at night, it adds a pop of bright blue to an otherwise dark gray block of commercial buildings.

Remodeling St. Paul’s Chancel

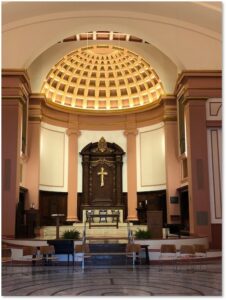

From 1913 to 1927 Concord architect Ralph Adams Cram remodeled the chancel of St. Paul’s with classical styling. He gave it a coffered and gilded half-dome, an elaborately carved wood reredos, a chancel organ, and choir benches.

A labyrinth on the floor of the main hall, an ancient meditative tool, is modeled after one in Ravenna, Italy. You can enter the labyrinth from anywhere (there are no pews) and follow the path to the center. Use the gentle, repetitive movement to pray, think, or quiet your mind.

The second renovation that included the “Ship of Pearl” pediment sculpture also added glass panels to the front of the building as well as skylights, an elevator, and upgrades to its heating and cooling systems.

The glass chapel, visible from the street, offers a quiet place for prayer and reflection. It honors the Church of St. John the Evangelist that was formerly located on Bowdoin St. in Boston. Andrew Young and Pearl River Glass Studio in Jackson, Mississippi, designed and crafted the window.

St. Paul’s was designated a cathedral in 1912, after the downtown neighborhood had become more commercial and less residential. It became the seat of the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts and was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1970.

Historical Note: Dr. Joseph Warren, the Revolutionary hero killed at the Battle of Bunker Hill, was interred in the crypt of St. Paul’s after it was completed. His remains were moved to the Warren family plot in Forest Hills Cemetery in 1855.