Monday Author: Susanne Skinner

The Chinese New Year is rich with tradition, superstition and history. 2021 celebrates the Year of the Ox, from Friday February 11th through February 26th. The Ox (one of 12 zodiac signs) symbolizes power in Chinese culture.

The Chinese New Year is rich with tradition, superstition and history. 2021 celebrates the Year of the Ox, from Friday February 11th through February 26th. The Ox (one of 12 zodiac signs) symbolizes power in Chinese culture.

Zodiac animals carry astrological and social significance. Each sign represents certain characteristics and people are said to have the personality of their zodiac animal. An Ox is hardworking and honest; an Ox year is hopeful and fruitful.

The Lunar New Year

Often called the Lunar New Year, this is the most important of China’s ancient festivals. Businesses close for weeks and people take extended vacations. Chinese New Year marks the first new moon of the lunisolar calendar. This calendar is traditional to east Asian countries (China, South Korea, and Vietnam) which are regulated by the cycles of the moon and sun.

The date of the New Year always falls on the second new moon after the December 21st winter solstice.

A Variable Date

The dates of the Chinese New Year vary. It begins with the New Moon and ends on the Full Moon, from the first day to the 15th day of the first month of the new year.

A solar year (the time it takes Earth to orbit the sun) is 365 days. A lunar year, (12 full cycles of the Moon), is 354 days. The moon still defines a month, but an extra month is added periodically to align with the solar year, so the new year falls on a different day within that month-long window.

A solar year (the time it takes Earth to orbit the sun) is 365 days. A lunar year, (12 full cycles of the Moon), is 354 days. The moon still defines a month, but an extra month is added periodically to align with the solar year, so the new year falls on a different day within that month-long window.

The Lantern Festival, a 2000-year-old tradition, marks the final day (the 15th day of the first lunar month). After the Lantern Festival, traditional restrictions are lifted and decorations are removed.

The Spring Festival

In mainland China, the new year is the Spring Festival. While the Chinese New Year and the Lunar New Year are similar, they have nuanced differences.

The Spring Festival was an attempt to westernize the celebration; popularized after Communist Party leader Mao Zedong took power in 1949. The party used it extensively to replace the term new year, eliminating traditions based on superstitions and religion. Lion and dragon dances were deemed unsuitable for an atheist country.

The Legend of Nian The Dragon

The origin of the Spring Festival is difficult to trace. It is widely believed the word Nian (the Chinese word for year), is the name of a dragon that preyed on humans at the beginning of each new year.

An old man offered to subdue Nian by asking him to swallow other beasts, telling him “people are by no means your worthy opponents.” Nian agreed, thus protecting the people from harm. Stories claim the old man was an immortal fairy who then disappeared riding upon Nian’s back.

An old man offered to subdue Nian by asking him to swallow other beasts, telling him “people are by no means your worthy opponents.” Nian agreed, thus protecting the people from harm. Stories claim the old man was an immortal fairy who then disappeared riding upon Nian’s back.

Before leaving, he told the people red-paper ornaments in their windows and doors would scare Nian should he attempt to return. According to legend, red is the color Nian fears most. The custom of decorating with red paper and firecrackers to scare away Nian is an enduring part of the celebration.

Some say Nian still exists, hiding in the mountains.

Good Luck Arriving

The lunar new year is shaped by tradition and luck is a central theme throughout the celebration. It is most often depicted in the form of a calligraphy character on a square of red paper, hung in a diamond shape.

The lunar new year is shaped by tradition and luck is a central theme throughout the celebration. It is most often depicted in the form of a calligraphy character on a square of red paper, hung in a diamond shape.

The character, which means good luck, hangs upside down to welcome in the new year. It proclaims the family’s wishes for prosperity, good fortune and health. The phrase to arrive or to begin is a homophone (same word with a different meaning) for upside down. The symbol is intended to show good luck pouring down upon the recipient.

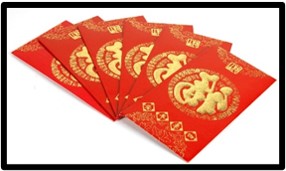

Red Envelopes of Money

Red symbolizes good fortune in Chinese lore. The red envelope is believed to bring luck to the person who receives it and to the one who gives it.

The envelopes are decorated with gold Chinese characters, typically happiness and wealth. Unlike a Western greeting card, red envelopes given at Chinese New Year are typically left unsigned and never opened in front of the giver.

The money inside must be new and crisp. Folding the money or giving used bills is in bad taste. Coins and checks are avoided, the former because change is not worth much and the latter because checks are not common in Asia.

The money inside must be new and crisp. Folding the money or giving used bills is in bad taste. Coins and checks are avoided, the former because change is not worth much and the latter because checks are not common in Asia.

Some companies give workers a year-end cash bonus tucked inside a red envelope and they are also given at birthdays and weddings.

New Year Superstitions

Symbolism is taken seriously and welcoming in the new year includes a list of things one can and cannot do.

Arguing and crying top the Do Not Do list, as both are negative emotions. Being happy and conversing about good things sets a positive tone for the new year. It is bad luck to enter the year with debit, so all obligations must be paid before the new year begins.

Bad luck continues if you sweep the floor after the lunar New Year’s Eve because you risk sweeping away accrued wealth and fortune. Washing one’s hair or laundry on the first day is seen as rinsing away good karma.

Scissors carry negative connotations because they denote severed connections during a time of togetherness and reunion. This includes cutting your hair—taboo during official celebration days.

Scissors carry negative connotations because they denote severed connections during a time of togetherness and reunion. This includes cutting your hair—taboo during official celebration days.

Colors play a significant role in Chinese superstitions. Wearing black or white is discouraged as both colors are associated with mourning. Red is the preferred color because it attracts success, happiness and luck.

Go Forth and Prosper in the Year of the Ox

One of the most traditional greetings for Chinese New Year is the Cantonese kung hei fat choi. The literal translation is Greetings, Become Rich!

May your new Year of the Ox be a time of looking forward, celebrating new beginnings, good health, prosperity and family.