Watching “The Menu” this weekend, I was struck by how the public image of a restaurant chef has changed over decades. This was reinforced on Monday by the news that Noma, the world’s finest restaurant, is closing.

The Cook in the Kitchen

After WWII, no one in America thought much about chefs. Even if you could afford to hire a private chef, you referred to him (or more likely her) as the cook. Restaurants and diners had cooks. The Armed Forces had cooks. Trains had cooks. Their job was to produce filling and nutritious meals that kept diners going through a day that probably included hard physical labor.

If you thought about the cook at all (unless, as in our house, it was Mom) he was the guy in the grease-stained white outfit with the white hat standing over a hot grill in the kitchen.

If you thought about the cook at all (unless, as in our house, it was Mom) he was the guy in the grease-stained white outfit with the white hat standing over a hot grill in the kitchen.

Nobody cared how the meal was “plated” and whether the arrangement of food was aesthetically pleasing. In fact, no one talked about plating: you put the meatloaf, mashed potatoes and green beans on a plate and served it. A cook would never have created oyster foam or tomato water. Trends like “tall food” and smears of sauce that look like a Picasso painting did not put a gleam in a cook’s eye.

The French Chef Debuts

That all began to change in 1963 when Julia Child debuted The French Chef on public television. The show, along with her best-selling cookbook, “Mastering the Art of French Cooking,” brought French cuisine to a country obsessed with canned vegetables, processed foods, and TV dinners. Ms. Child not only taught us how to cook better meals, she taught Americans what constitutes good food and why eating it is important.

That all began to change in 1963 when Julia Child debuted The French Chef on public television. The show, along with her best-selling cookbook, “Mastering the Art of French Cooking,” brought French cuisine to a country obsessed with canned vegetables, processed foods, and TV dinners. Ms. Child not only taught us how to cook better meals, she taught Americans what constitutes good food and why eating it is important.

When The French Chef came on, Mom would sit with a notepad and copy down the recipe, including directions. I still remember the first meal she put on the table from a Julia Child recipe. It was a pork loin cooked with mushrooms and Marsala wine. Although Mom was an excellent cook, she had never served anything like this before. It was a revelation. I have since tried and failed to recreate it.

The Food Scene Heats Up

Other cooking shows followed in the seventies, building on Julia Child’s success. Americans became acquainted with chefs like James Beard, Joyce Chen, Graham Kerr, and Jacques Pepin. The eighties brought us Martha Stewart and Emeril Lagasse, Still, these chefs were seen simply as experts in their craft. They appealed only to people who enjoyed cooking and eating good meals, although the term “foodie” did not exist.

The TV cooking scene heated up when Food Network arrived in 1993 and that’s when the perception of chefs began to change. Shows shifted from good-natured, avuncular teachers who followed the Julia Child model to driven performers. The new chefs evolved from martinets demanding perfection to bullies belittling the unprepared or unworthy, to minor gods whose every order must be obeyed.

The TV cooking scene heated up when Food Network arrived in 1993 and that’s when the perception of chefs began to change. Shows shifted from good-natured, avuncular teachers who followed the Julia Child model to driven performers. The new chefs evolved from martinets demanding perfection to bullies belittling the unprepared or unworthy, to minor gods whose every order must be obeyed.

I think what drove the evolution was cooking contest programming. You can’t be chatty, cheery, and gracious when you’re working under the clock to produce a dish that will win you thousands of dollars, create future opportunities, allow you to open your own place, and make you a household name.

(Full disclosure: I have watched many of these episodes of Iron Chef and Chopped and enjoyed them all.)

Iron Chef and Kitchen Stadium

Iron Chef began the process in 1993 with its remake of a Japanese show called Ryōri no Tetsujin, or Ironmen of Cooking. The patented format, with Host Takeshi Kaga, calling the shots in Kitchen Stadium. Guest chefs competed in cook-off against “a pantheon” of Iron Chefs to produce dishes along a theme. If they won, they became an Honorary Iron Chef with the opportunity to join the exalted panel of regulars.

The vibe was high-pressure, with commentators describing the cooking process, and high-tech with flashing lights, shiny surfaces and flashing knives. Every cook-off began with Kaga-san shouting dramatically “Let the battle begin.”

The vibe was high-pressure, with commentators describing the cooking process, and high-tech with flashing lights, shiny surfaces and flashing knives. Every cook-off began with Kaga-san shouting dramatically “Let the battle begin.”

Iron Chef spun off many celebrity chefs who went on to fame and fortune in other Food Network shows as well as opening their own restaurants.

Gordon Ramsay

Chef Gordon Ramsay took this process to a more disturbing level. The names of his television shows in the U.K. and U.S. say it all: Kitchen Nightmares, Hell’s Kitchen, Hotel Hell and MasterChef US. His shows feature contestants enduring rounds of insults, deprecation, humiliation, and scorn from the celebrity chef.

Where Iron Chef added humor and education to the hard-fought battles, Chef Ramsay relied on ego and brutality to make his points. It worked for some people, certainly. Viewers have made him famous and they flock to his world-wide chain of restaurants.

I have never found humiliation and negative criticism to be an effective means of educating someone, however. Also, I do not enjoy this behavior, so I never watched these shows.

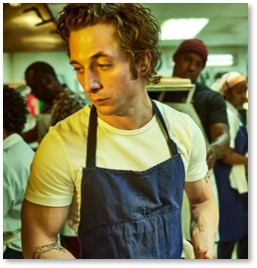

The Bear

This series on Hulu (which I watch at my daughter’s house) follows a sous-chef (pronounced su-chef) from New York City’s Eleven Madison Park to a lowly sandwich shop in Chicago that he inherits from his uncle. There, he attempts to impose the discipline of a fine-dining kitchen on the chaos of the family business, elevating the food to new levels.

The existing kitchen staff resists this, of course, which creates the drama and emotional fireworks. I frequently wish someone would dunk his mouthy cousin’s head in a vat of mustard. But we also see flashbacks of his time at what has been named America’s finest restaurant. It is not a pretty picture. The unnamed Executive Chef berates him in a series of brutal insults that culminate in, “You should be dead.” This makes a great segue to …

The existing kitchen staff resists this, of course, which creates the drama and emotional fireworks. I frequently wish someone would dunk his mouthy cousin’s head in a vat of mustard. But we also see flashbacks of his time at what has been named America’s finest restaurant. It is not a pretty picture. The unnamed Executive Chef berates him in a series of brutal insults that culminate in, “You should be dead.” This makes a great segue to …

… The Menu

The Menu gives us chef as psychopath. He’s a celebrity so condescending toward his customers that he treats them with murderous contempt that follows logically to outright murder.

In this movie, Ralph Fiennes sets up a dinner of revenge against the customers who offend him the most. The “lavish menu” takes the meal to extremes unthought of by any restaurant diner. I can’t say more without getting into spoilers. Suffice it to say that Chef Slowik is totally off the rails.

In this movie, Ralph Fiennes sets up a dinner of revenge against the customers who offend him the most. The “lavish menu” takes the meal to extremes unthought of by any restaurant diner. I can’t say more without getting into spoilers. Suffice it to say that Chef Slowik is totally off the rails.

Yet his kitchen staff, known as the brigade (pronounced bree-gahd) responds to his every order with unform and robotic responses of, “Yes, Chef!” Beware the psychopath: he will destroy you.

Where Do Kitchens Go from Here?

Education turned to competition, which changed to tyranny. But where did the model of kitchen brutality come from in the first place? And how is it changing now? See the next post for some answers and ideas.