Boston has a lot of statues and most of them, as often noted, are of dead white men. We have more statues of animals than of women. Statues of sports heroes outnumber monuments to notable African Americans — with only one overlap.

Boston has a lot of statues and most of them, as often noted, are of dead white men. We have more statues of animals than of women. Statues of sports heroes outnumber monuments to notable African Americans — with only one overlap.

The irony lies in the fact that one of our best- known and most-visited memorials honors black soldiers.

Eight Statues for Black History Month

In honor of Black History Month, today’s post lists eight statues of African-Americans: as many as I could find. One holds a prominent position opposite the Massachusetts State House while others can be found in more remote locations. Some are great but I think at least one should be removed and retired.

1, Robert Gould Shaw Memorial

- Sculptor: Augustus Saint Gaudens

- Architectural Setting: McKim, Mead and White

- Location: 24 Beacon Street, opposite the State House

While named for the Boston Brahmin colonel who commanded the regiment, this statue depicts the men of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry marching down Beacon Street on May 28, 1863. Armed and on their way to fight for the Union, these men stand tall and walk proudly. Their faces show resolve and determination. Both historically and artistically, this masterpiece of American art deserves its status among the greats. It also deserves the crowds who come to see it, from tourists to schoolchildren on field trips. The National Gallery of Art in Washington DC displays a model.

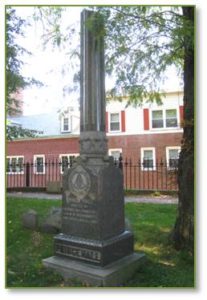

2, Crispus Attucks / Boston Massacre Monument

- Sculptor: Robert Kraus

- Location: Boston Common between Tremont St. and Avery St.

This statue honors the five victims of the Boston Massacre: Crispus Attucks, James Caldwell, Patrick Carr, Samuel Gray and Samuel Maverick. At the base of a granite obelisk 25 feet high stands a figure representing the Spirit of Revolution.

Inspired by Eugene Delacroix’s painting of “Liberty Leading the People.” the figure holds the American flag In her left hand while the right brandishes a broken chain. A bronze bas relief embedded in the base depicts the event and includes an image of Crispus Attucks (1723 – March 5, 1770) lying dead in the street.

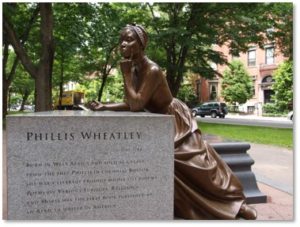

3. Phillis Wheatley in the Boston Women’s Memorial

- Sculptor: Meredith Bergmann

- Location: Commonwealth Avenue Mall between Fairfield St. and Gloucester St.

This bronze grouping depicts three women who helped to shape Boston’s history and were important contributors to Boston’s history. Ms. Wheatley (1752 – 1784) was our first African-American poet and the first African-American writer to publish a book, “Poems on Subjects Religious and Moral,” in the United States.

This bronze grouping depicts three women who helped to shape Boston’s history and were important contributors to Boston’s history. Ms. Wheatley (1752 – 1784) was our first African-American poet and the first African-American writer to publish a book, “Poems on Subjects Religious and Moral,” in the United States.

Along with Abigail Adams and Lucy Stone, Ms. Wheatley’s statue has a plinth but she doesn’t stand on it, looming above us all. Instead, she leans pensively against the granite block at ground level, perhaps composing a new poem. You can just walk up and say hello.

4. Prince Hall Monument in the North End

- Sculptor: Unknown

- Location: Copp’s Hill Burying Ground

Prince Hall (1748 – 1807) founded the first Black Lodge in the Masonic Order and became its Grand Master. He was a skilled orator, a prominent citizen of Boston and a leader of the African-American community in the 18th Century. He distributed anti-slavery petitions and pointed out the irony of colonies fighting for their freedom while denying it to their black citizens.

Prince Hall (1748 – 1807) founded the first Black Lodge in the Masonic Order and became its Grand Master. He was a skilled orator, a prominent citizen of Boston and a leader of the African-American community in the 18th Century. He distributed anti-slavery petitions and pointed out the irony of colonies fighting for their freedom while denying it to their black citizens.

Today, Prince Hall Grand Lodges exist in the United States, Canada, the Caribbean, and Liberia numbering some 4,500 lodges worldwide, with a membership of over 300,000 Masons. Prince Hall lies beneath a simple stone marker in the southwesterly corner of Copp’s Hill Burying Ground, near the intersection of Charter St. and Snow Hill streets. A polished black granite obelisk serves as his memorial.

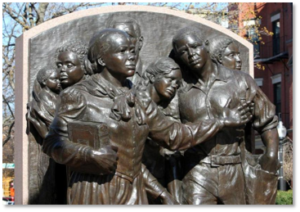

5. Harriet Ross Tubman Memorial

- Sculptor: Fern Cunningham

- Location: Harriet Tubman Park, South End

This 10-foot bronze piece was the first sculpture on city-owned land to memorialize a woman. It shows the fiery abolitionist doing what she is best known for: leading slaves to freedom as a “conductor” on the Underground Railroad.

This 10-foot bronze piece was the first sculpture on city-owned land to memorialize a woman. It shows the fiery abolitionist doing what she is best known for: leading slaves to freedom as a “conductor” on the Underground Railroad.

Ms. Tubman had strong links to Boston’s abolitionist movement. Active with the Massachusetts 54th Regiment, she was present with them during the attack on Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863. She also spied on Confederate forces and worked as a cook and a battlefield nurse during the Civil War. Ms. Tubman later wrote a poetic tribute to a battle:

“And then we saw the lightning, and that was the guns; and then we heard the thunder, and that was the big guns; and then we heard the rain falling, and that was the drops of blood falling; and then we came to get in the crops, and it was the dead men that we reaped.”

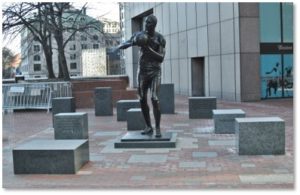

6. Bill Russell

- Sculptor: Ann Hirsch

- Location: City Hall Plaza, Government Center

Bill Russell (1934 – ), a 6-foot-10-inch center from Monroe, LA., was a five-time NBA MVP and a 12-time All-Star. As Boston’s first black star athlete, he helped the Celtics win 11 championships in 13 seasons from 1956-69, a feat that no athlete on a major American professional team has duplicated.

Bill Russell (1934 – ), a 6-foot-10-inch center from Monroe, LA., was a five-time NBA MVP and a 12-time All-Star. As Boston’s first black star athlete, he helped the Celtics win 11 championships in 13 seasons from 1956-69, a feat that no athlete on a major American professional team has duplicated.

Mr. Russell encountered problems with the city’s fans, however, and his attitude towards Boston has been described as “well-founded animosities.” The statue of Mr. Russell in his playing days is surrounded by 10 granite blocks for a total of 11 elements, representing Mr. Russell’s 11 NBA championships. Each plinth features a word and corresponding quotation that highlight Russell’s accomplishments on and off the court. The man who never wanted a statue (“Pigeons defecate on statues.”) has a statue in the city that only seemed to love him at home games.

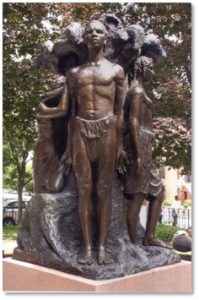

7. Spirit of Emancipation

- Sculptor: Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller

- Location: Harriet Tubman Park, South End

This African-American sculptor, a leading artist of the Harlem Renaissance Movement, created a plaster grouping in 1913 for the National Emancipation Exposition in New York City. The event commemorated the 50th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation.

This African-American sculptor, a leading artist of the Harlem Renaissance Movement, created a plaster grouping in 1913 for the National Emancipation Exposition in New York City. The event commemorated the 50th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Cast in bronze in 1999, “Spirit of Emancipation” was placed in Harriet Tubman Park to celebrate the park’s 15th anniversary. The statue depicts a man and two women emerging from the Tree of Knowledge. Tall and resolute, their faces show a determination to succeed in creating a new life for themselves. The sculpture focuses on the spirit and will of it subjects and dispenses with the traditional symbols of slavery and emancipation that were typical of the period.

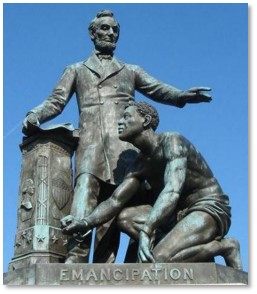

8. The Emancipation Group

- Sculptor: Thomas Ball

- Location: Park Square

I left this one for last because, frankly, I think it should be removed and stored somewhere out of sight. Controversial even when it was unveiled, it depicts a slave crouched subserviently at the feet of Abraham Lincoln.

I left this one for last because, frankly, I think it should be removed and stored somewhere out of sight. Controversial even when it was unveiled, it depicts a slave crouched subserviently at the feet of Abraham Lincoln.

The President has raised a hand over the man in the act of freeing him. Unfortunately, the image conveys dominance more than emancipation. Critics have compared the slave’s position to kneeling in gratitude, being patted, or “polishing Lincoln’s boots.”

We may love Thomas Ball’s statue of George Washington in the Public Garden but this sculpture reflects the man’s racist views. These were so strong that he would not use a black man as a model for the slave but instead used his own body. The Emancipation Group is not even an original work but a copy of a statue Mr. Ball did for Washington, DC. Boston can do better than this. Let’s get rid of it and replace it with the statue of a black man or woman of accomplishment.

UPDATE 2021: Due to public outcry and a petition, The Emancipation Group was removed and put into storage. The plinth remains empty.

Black History Month and Boston History

There you have it: eight statues of notable African Americans around the city for Black History Month. While these are more than I expected to find, I have to wonder how we could have so many statues of athletes, from shot-put to running to hockey, with only one of them a black man.

Boston likes to think of itself as Oliver Wendell Holmes’s Hub of the Universe and John Winthrop’s Shining City on a Hill, a stronghold of abolitionists and currently a center of Liberal and Progressive politics. Underneath all that, however, lies a current of racism that now and again rears its ugly head in unexpected ways. Sometimes what we don’t do, don’t pay attention to, or don’t think about is more important that what we actually do.

Perhaps for Black History Month we should take some time to think about what we haven’t done in regard to recognizing more people of color who have made a contribution to the city.