Part One: How to Hide a Giant Building

In a post about Boston’s hidden gems, I must acknowledge that it’s not easy to hide an entire nineteenth-century granite courthouse and the headquarters of the Massachusetts judicial branch of government. It’s also not easy for a building to turn such a blind eye to the city that the city can’t see it at all. But Boston did it.

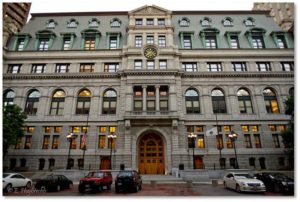

No Romulan cloaking device or Hogwarts cloak of invisibility conceals the John Adams Courthouse. It does have a mask, however, and a total lack of signage pointing to the front door.

One can walk along Tremont Street and Cambridge Street from King’s Chapel to Police Headquarters and back again or from City Hall to Boston Common without ever knowing that this enormous structure exists. Like Brigadoon or Shangri-La, the John Adams Courthouse appears only when you’re not looking for it.

Yet, even when you know how to reach the courthouse, you will never see the front of it directly from the street because of the enormous semi-circular mask known as Center Plaza. Look up the flights of stairs leading through Center Plaza to what was once a beautiful garden and all you will see are the grills of cars in an employee parking lot. Is there a building up there? Really? Are you sure?

We Would Never Have Found It

After I recently took the Bell Tour at King’s Chapel I asked the nice couple from Tennessee who climbed up the bell tower with me what they planned to do next.

“We’re going to try to find the John Adams Courthouse,” they replied.

“Oh, that’s where I’m going, too,” I said as I was planning a post about the courthouse and wanted to go inside. “I’ll take you there.” So I did. We walked down Tremont, up a flight of stairs alongside Center Plaza and into what I can only think of as the Pemberton Parking Lot. “There it is,” I said, pointing to the front door.

“Thank you for taking us,” the woman said. “We would never have found this on our own.”

Exactly.

In today’s post, I’ll talk about how this sad situation came about because the shape of the land defines the building that obscures the courthouse. Next week I’ll discuss the building, a beautiful and unappreciated gem of art and architecture that deserves more recognition and respect than it receives.

The Demise of Pemberton Hill

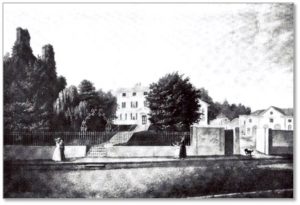

In the beginning, Pemberton Hill made up one third of the Tri-Mountain, along with Beacon Hill and Mount Vernon. Half of its four and a half acres belonged to Gardiner Greene, a wealthy merchant and real estate speculator who cultivated a series of celebrated gardens behind his mansion. Later this property, along with the other houses on Pemberton Hill, was purchased by Patrick Tracy Jackson for the Boston and Lowell Railroad. They paid an amount that would now be worth nearly $4 million.

The B&L Railroad scalped Pemberton Hill, taking off the top 65 feet. They used this dirt and gravel to fill the flat lands in the Charles River north of Causeway Street on which they built a new depot and three new streets: Nashua, Lowell and Andover. Gardiner Greene’s spectacular garden vanished beneath workmen’s shovels but they did save its gingko tree, transplanting it on Boston Common.

Gracious Residences in Pemberton Square

Jackson laid out house lots on the leveled hill, now renamed Phillips Square, to form a “gracious residential development” modeled on those in London. Alexander Wadsworth, a surveyor, won Jackson’s contest to develop the square. Following that, George Minot Dexter designed the houses and the cast-iron fences around the front yards and the central garden along with its lamp posts. Dirt from the foundations also went into filling the flats.

The development, renamed Pemberton Square in 1838, formed a bow with a curved eastern side. Mr. Dexter designed its three-story red-brick, bow-fronted town homes for Boston’s finest citizens. The straight western side had four-story homes with flat facades. In the center of the “square” an elliptical garden offered residents shade and privacy. Had it survived, it might look today like Louisberg Square on Beacon Hill.

Cambridge Street, which becomes Tremont Street, curves around what had been the eastern end of the Tri-Mountain and provides the only extant reminder of Pemberton Hill,

From Residential to Commercial

By the beginning of the Civil War, residents had moved to other parts of the city, such as the South End and the Back Bay, and professional men like lawyers and architects used Pemberton Square to establish their stability and credibility. These included Gridley J.F. Bryant and Edward Clarke Cabot, who designed some of Boston’s finest buildings. Schools and universities moved in while municipal departments and charitable organizations opened offices. By 1875 these new tenants filled Pemberton Square. The Boston Society of Architects made its first home there.

Ten years later, the city selected Pemberton Square as the site of its new courthouse and razed the row houses on the west side along with the central garden. Construction of the Suffolk County Courthouse, also known as the John Adams Courthouse, began in 1893.

What was left of the bow-front houses on the east side of the square held on by their doorsteps until the early 1960s when they fell to urban renewal and the construction of Government Center.

The Mask: Center Plaza

Now you understand why the three-building Center Plaza office complex is curved, following the curve of the street, which followed the curve of what is now just a shoulder of Beacon Hill. Center Plaza went up when urban renewal replaced the old Scollay Square with the multi-building Government Center. Built by developer Norman B. Leventhal, this 720,000 square-foot commercial building wraps around the former Pemberton Square and separates it from the street.

Center Plaza has received insults on its merits with terms like “hulking” and “mundane” but seldom have critics noted its role in completely blocking the view of the John Adams Courthouse behind it. Instead of opening the courthouse to the new Government Center, thus connecting it to City Hall and linking the judicial and administrative functions, the architects turned their backs on nineteenth-century elegance in favor of a forgettable contemporary structure.

Next week I’ll move on to the hidden beauty of the courthouse and why it’s worth turning your own back on Center Plaza to enjoy this building inside and out.