I often wonder what impact this crisis will have on younger people who are supposed to be working and earning right now.I’m not talking about the big lessons that will keep a disaster like this from happening again. My concern is with the the ones that will affect their everyday decisions.

I have no doubt the pandemic will scar them and affect their behavior for the rest of their lives. Will their lessons from the pandemic be to take charge or to give up?

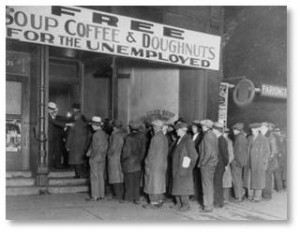

Lessons from the Great Depression

Those of us in the Boomer cadre grew up with parents who had been traumatized by the Great Depression’s hardships. That economic crisis altered their behavior forever.

- Use it up

- Fix it up

- Make do

- Waste nothing

- Do without

- Avoid debt

- Don’t trust banks

- Pay cash for everything

- Always keep cash on hand

If my parents threw out a broom, Dad would cut off the handle and keep it because you never knew when you might need a good dowel. Our basement was filled with these things—which were, by any standard, better made than products are today.

Saving and Hiding

When we cleaned out the house before its sale, we found things in closets, under beds, in cabinets, and tucked up under the floor joists in the basement. If we’d had a garage, I’m sure that would have been full, too.

Dad insisted on always having some cash in the house because the banks might close without warning. He didn’t trust banks much. My brother and I took some valuables out of the house and put them in a safe deposit box. He removed them from the box and put them back in his hiding place.

Lessons from the Pandemic

So, what will today’s young people learn from the Covid-19 pandemic? If, like politicians, you never let a good crisis go to waste, you can make something good out of a terrible time.

I can think of one lesson that would be positive: Save Money.

Having the financial rug pulled out from under young people might demonstrate the value of both saving and investing money. Save some to have it on hand for a crisis. Invest some so it will grow and you will have a safety net in the future.

Being dependent on the vagaries of a government that functions neither smoothly nor quickly might teach them to:

Being dependent on the vagaries of a government that functions neither smoothly nor quickly might teach them to:

- Plan ahead

- Rely on yourself

- Prepare for a rainy day

Deciding that it’s more important to put some money away than it is to buy new skis, get another tattoo, or purchase the latest expensive smartphone would be a good thing.

Thinking Outside the Box

When I heard how long it would take to develop a safe vaccine, I thought—as I’m sure many people did—that this was ridiculous. Now, I’m not a doctor, or a scientist so I can’t get into the whys and hows of developing a vaccine.

What I do know is that the opportunity cost of taking that long is huge. A lot of people can become infected, spread the disease, and die in the 12 to 18 months experts tell us it will take to get from Patient Zero to Herd Immunity. Not to mention tanking the economy and driving America into recession.

Performing Meatball Surgery

I also thought of an episode of the old M*A*S*H TV series, the one where Maj. Charles Winchester III (David Ogden Stiers) arrives from Boston and begins working in the MASH unit. He does a bowel resection on a wounded solder and is closing up when Hawkeye Pierce (Alan Alda) asks him what he’s doing.

I also thought of an episode of the old M*A*S*H TV series, the one where Maj. Charles Winchester III (David Ogden Stiers) arrives from Boston and begins working in the MASH unit. He does a bowel resection on a wounded solder and is closing up when Hawkeye Pierce (Alan Alda) asks him what he’s doing.

Winchester explains the detailed technique he’s following to finish the surgery and close up. Hawkeye tells him to just close up, explaining, “This is meatball surgery.” He adds that speed beats technique in meatball surgery because while you’re working on meticulous details and perfect technique, the next guy in line will die. Maybe the next two, as well.

The current process for developing a safe vaccine strikes me as a case of technique—and process—over speed. I can only imagine what Steve Jobs would have said when told a vaccine would take 12 to 18 months.

The New Manhattan Project

Mr. Jobs might, in fact, have said exactly what chemist and entrepreneur Stuart Schreiber said when told how long a safe vaccine would take: “How about six months?”

Mr. Schreiber is part of a group founded by Dr. Tom Cahill and described in yesterday’s Wall Street Journal. “The Secret Group of Scientists and Billionaires Pushing a Manhattan Project for Covid-19” by Rob Copeland. They “…are marshaling brains and money to distill unorthodox ideas gleaned from around the globe.”

The group, Scientists to Stop Covid-19, includes chemical biologists, an immunobiologist, a neurobiologist, a chronobiologist, an oncologist, a gastroenterologist, an epidemiologist and a nuclear scientist, among others. “They are working remotely as an ad hoc review board for the flood of research on the coronavirus, weeding out flawed studies before they reach policy makers.”

Working Better and Faster

They are also leveraging money, knowledge, contacts and influence to make things happen faster. Sometimes this means twisting arms to shrink approval times, making a phone call to cut through red tape, and ordering officials to bypass obstructive regulations. This is the kind of thinking that will take us where we need to go faster and better than following the established route.

They are also leveraging money, knowledge, contacts and influence to make things happen faster. Sometimes this means twisting arms to shrink approval times, making a phone call to cut through red tape, and ordering officials to bypass obstructive regulations. This is the kind of thinking that will take us where we need to go faster and better than following the established route.

If I had any qualifications, I would volunteer to help. At the very least, I urge everyone to read this article and understand what can be done when you don’t accept the status quo and are willing to break the mold. I really, really hope they succeed.

Shattering the Box

The lesson here? Break the mold.

Think outside the box—yes. But shatter the box when needed. Don’t accept the limitations created by the way things have always been done. Do them differently because we just can’t wait. ‘

This is a terrible time for the country and for everyone in it. I have no doubt that it will affect younger generations. Their lessons from the pandemic will probably be very different from what my parents learned in the Great Depression.

Will they learn something positive or take away only negatives? Time will tell.

More importantly, what will be your lessons from the pandemic?

For me the adage “you don’t know what you’ve got till its gone” is updated to “you knew what you had, you just never thought you’d lose it.” I have renewed appreciation for little things and thank my parents for teaching me how to save.