Another conversion of a commercial office building to residential housing has been announced at 50 Congress Street and once again, it’s an interesting building. This should come as no surprise, given the number of architecturally or historically interesting buildings in the city. In fact, despite its decorated façade, this one doesn’t make any of the books on my shelf about Boston architecture.

The Status of Residential Conversions

The Status of Residential Conversions

Currently, Boston has 22 official applications for such conversions but has disclosed only five addresses. The city is keeping mum with the full address list for the remaining 17 projects.

The 22 applications under Mayor Michelle Wu’s tax incentive program cover 1.2 million sq ft across 27 buildings. They will produce 1,517 new homes, mostly either apartments or condominiums. Four projects are already under construction, and one is fully occupied. The conversions are located primarily in these five neighborhoods:

- Financial District (12-14 projects)

- Downtown Crossing (4-5 projects)

- Chinatown periphery (1-32 projects)

- Edge of the Back Bay (1 project)

- Government Center/Beacon Hill edge (2-3 projects).

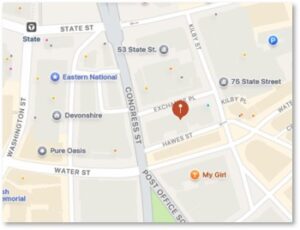

The Second-Largest Conversion Project

The latest announcement concerns 50 Congress Street, a 10-story building between Exchange Place and Hawes Street in the Financial District. Currently an office building with ground-floor retail, it will be converted to 171 apartments above the retail shops. It will be the second-largest office-to-residential project in Boston after 294 Washington Street.

The proposal, which was filed on Feb 26, sets aside 20% of the units as affordable and includes roughly 6,300 SF of ground-floor retail.

50 Congress Street

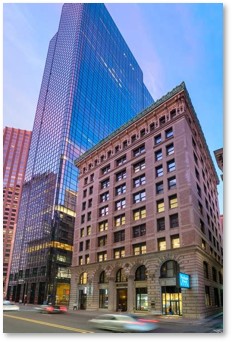

The building at 50 Congress Street, designed by the architectural firm of Andrews, Jacques, and Rantoul, originally served as the headquarters for the State Mutual Life Insurance Company. Built in 1910, its early 20th‑century commercial architecture complements Boston’s financial district with classical proportions and a robust masonry façade.

The structure fits into the family of Beaux‑Arts–influenced commercial blocks that dominated Boston’s downtown in the early 1900s. Consistent with both Boston’s conservative approach and the Financial District’s desired projection of stability and dependability, it is formal but not flamboyant.

Classically ordered, it is also commercially pragmatic. In fact, it sits so comfortably among neighboring structures from the same era, it forms part of the cohesive architectural fabric of buildings near Post Office Square. I have driven past it hundreds of times but never really taken note of it.

The Architectural Elements

50 Congress Street does not approach busy Baroque ornamentation, but it does offer some interesting design elements.

The ground-floor “base” is constructed of heavier stonework at the street level to create a visual “pedestal.” Subtle classical moldings wrap around the main entrance while Corinthian columns separate the three arched doorways. Stone piers frame the tall storefront openings and medallions decorate the second floor.

The ground-floor “base” is constructed of heavier stonework at the street level to create a visual “pedestal.” Subtle classical moldings wrap around the main entrance while Corinthian columns separate the three arched doorways. Stone piers frame the tall storefront openings and medallions decorate the second floor.

Middle floors representing the building’s “shaft” have brick or light stone cladding with restrained details. Minimal ornamentation advertises commercial efficiency. Vertical window bays emphasize height and deliver light to the interior.

Upper floors , the “Capital” have slightly more decorative window surrounds. Cornice banding or simplified entablature mark the roofline. A modest projecting cornice is topped by a copper “chéneau,” at the roofline. These copper ornaments were typical of the period, although many Boston buildings removed theirs in the middle of the 20th century. This building kept its crown.

Interior Advantages at 50 Congress Street

Although the windows on the top floor are smaller than those lower down, they should deliver excellent views—at least on some side. Those looking northwest will have their views blocked by the giant black mass of Exchange Place.

As was typical of commercial buildings in the early 20th century, 50 Congress Street sports marble corridors with polished bronze accents. A beautiful marble staircase leads up from the lobby.

Movie buffs may note that several have been filmed in this part of the city, including Spotlight, R.I.P.D., and Free Guy. A sharp eye may catch 50 Congress Street in a scene or two.

Movie Sets and Sandwich Shops

The buildings 171 living units will bring more life to a part of Boston that can be very quiet at night and on weekends. Residents will also drive demand for the kinds of services that have been struggling post-pandemic. Sandwich shops, dry cleaners, cocktail bars, coffee shops, florists could see increased demand and an influx of new customers.

The buildings 171 living units will bring more life to a part of Boston that can be very quiet at night and on weekends. Residents will also drive demand for the kinds of services that have been struggling post-pandemic. Sandwich shops, dry cleaners, cocktail bars, coffee shops, florists could see increased demand and an influx of new customers.

50 Congress Street also gives residents easy access to T stops, Leventhal Park, Quincy Market, and Government Center,

It’s all good.