If you ever drove through Boston at Christmastime on the elevated Southeast Expressway, you know the Flour and Grain Exchange building. You couldn’t miss the granite structure with a pointed crown on top that sports a big, red holiday bow every year.

I have wanted to write about this building for some time but finally got the chance to spend some time in it last month. That was courtesy of Operations Manager Brian Amirault. We met by chance in the lobby and he generously offered to take me on a tour.

When an expert offers to give me a private tour, I jump at the opportunity

Historic and Festive

The Flour and Grain Exchange, as the building is officially known, is historic as well as festive. It began as a meeting hall for the Boston Chamber of Commerce after it consolidated two trade bodies, the Boston Commercial Exchange and the Boston Produce Exchange in 1885. They occupied the building from 1892 to 1902, when it changed to the Flour and Grain Exchange.

Completed in January of 1892 at a cost of $400,000, the structure was erected on land donated by Henry Melville Whitney. He was a developer who in 1887 consolidated virtually all of Boston’s horsecar companies into the West End Street Railway Company. In 1888 Mr. Whitney electrified a line running from Allston’s Braintree Street to Park Square in the Back Bay. In 1897 his company became the Boston Elevated Railway.

Architectural Design

The architectural firm of Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge (now known as Shepley Bulfinch), designed the Flour and Grain Exchange to create an impression of financial security for the city’s commercial circles. They succeeded with a building that almost flaunts the concept of solidity.

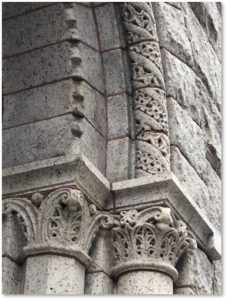

The Richardsonian Romanesque style developed by Henry Hobson Richardson, the architectural firm’s original principal, is characterized by:

- Rusticated masonry

- Multi-tiered arches

- Ornate decoration with foliate carving

- Tiered arched windows and arched doorways

- Clustered colonettes around windows and doors

The Flour and Grain Exchange Building itself has historically significance as an expression of the financial growth of Boston and a desire to advance the interests of trade and commerce in the city. The building is a contributing structure to the Custom House National Register District, an area characterized by 19th century commercial architecture.

The Beal Company restored the building’s exterior in 1988.

Structure of the Flour and Grain Exchange

The triangular plot on which the building sits is bounded by Milk Street, India Street, and Purchase Street, which runs along the Rose Kennedy Greenway. Built by the Norcross Brothers, the Flour and Grain Exchange rises seven stories high with two additional stories in a cylindrical turret at the corner of Milk and India Streets. Below the granite foundation, it stands on piles with each one holding seven and a half tons.

The exterior walls are made of pink granite from the Worcester Quarry in Milford, MA, A round cornice surmounts the structure and a row of crocket-finial, triangular attic dormers encircle it like the points on a crown. A conical roof covered with black slate tops the turret. The floors and ceilings of the offices occupying the sixth and seventh stories are suspended from this roof—an innovative construction technique.

Upon entering, you see that the floors of the vestibules and lower corridors are laid with marble tile. The vestibules and lower corridors have white Italian marble wainscoting. The interior finishes cut from quartered oak gleam with care and some of the doors have been decorated with elaborate carving. All the corridors above the first floor have oak wainscoting, with rift-sawn, yellow pine floors.

A Tour of the Flour and Grain Exchange

Mr. Amirault walked me through the whole building, including into the circular offices of the architectural firm under the turret’s conical roof. Then we ducked out a small door and I stepped onto the roof. From there I got an excellent view of the dormers that make up the “crown’s” points. I also got a pigeon’s-eye perspective on the nearby Custom House Tower and a great shot of Boston Harbor.

Mr. Amirault not only has a wealth of knowledge; he clearly loves the building and is proud of its beauty. I can understand how anyone who appreciates good architecture feels this way about a nineteenth-century building that was designed to be an “an ornament to the city and a credit to itself.” I wish the owners of Boston’s new glass towers shared those goals.

An Ornament to the City

One of the reasons I love nineteenth-century architecture is that the men who paid for these buildings wanted them to look beautiful. Modern buildings with their flat, plain glass curtain walls can never match this beauty. (I’m looking at you, Seaport District.)

Yes, this attention to appearance sprang from a combination of pride, status, and self-aggrandizement. But the structures that emerged truly are an ornament to the city, both inside and out.

We, the ordinary public, can enjoy architectural details like turrets, domes and towers, ornate carving, friezes,and polychromatic stonework as true works of art that enrich our lives. We need do nothing more than walk down the street — and pay attention — to enjoy them. Kudos to the men who made Boston’s beautiful buildings.

The Boston Flour and Grain Exchange

177 Milk Street

Boston , MA 02109