When I’m giving my Boston By Foot tours of the Victorian Back Bay, I sometimes have to wait as the duck boats and tour trolleys rumble through Copley Square so my voice won’t be drowned out. If your goal is to see as much of Boston as possible, these rolling tours are a good way to do it. If you want to get an in-depth explanation of what you’re seeing—well, not so much.

In their rush down one street after another, they just can’t give you the real flavor of the city or the kind of detail that makes Boston such a great place to just walk around. I hear the guides booming on their microphones, giving their passengers a two- or three-sentence description of each location as they hurry on to the next one. There’s a touch of information and maybe a few dates but no art or architecture, not much history, and no interesting stories.

Pointing Out the Treasures

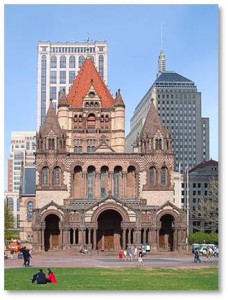

That’s exactly what @bostonbyfoot “tourees” get, though, and I love to point out the small treasures that give the Back Bay such a distinctive look among Boston’s neighborhoods. There’s so much to see that I could spend almost the whole tour in Copley Square alone and H.H. Richardson’s Trinity Church would take up at least half of that.

To give you an idea of what I mean, here are a few small treasures from the gifted hand of Mr. Richardson. One of America’s greatest architects, He would take on any design challenge and paid great attention to decoration. H.H. Richardson was responsible for many treasures of Boston’s Back Bay, both large and small.

The Trinity Church Cloister

When he designed this masterpiece, Henry Hobson Richardson wanted to make it a thing of beauty inside and out and he worked with an outstanding team of artists, sculptors, painters and glaziers to make it so.

One of the church’s true gems, however, is the cloister on the east side of the church. This tiny garden with a covered, arched walkway on three of its sides, offers a place of cool tranquility in the midst of a crowded and very busy area. With its mature plants, statue of St. Francis—patron saint of animals and the ecology—and tinkling fountain, it’s a gem that has to be seen up close to be appreciated. When I bring my tourees into the cloister, they frequently exclaim in surprise about how beautiful it is.

The Window Tracery

On the left side of the photo, you can see a Gothic window tracery from the Church of St. Botolph in Boston, Lincolnshire, England. Boston is actually a corruption of Botolph’s town (or stone) and this gives Trinity Church a link from one Boston church to another.

On the top right is a checkerboard pattern made from two colors of granite. This is a design scheme called polychromy and Richardson introduced it to Boston as part of his mature “Richardsonian Romanesque” style. The church’s front façade has both checkerboard and chevron patterns in polychromic stonework.

The Granite Rosette

Inside the walkway on the left but not visible in the photo, is a granite rosette that came from the old Gothic church on Summer Street, which burned in the Great Fire of 1872. There’s also a plaque expressing appreciate of Richardson for his work on the church. I point out both of these items, which are invisible to vehicles passing on the street.

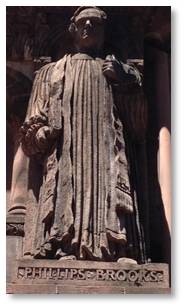

The Western Porch of Trinity Church is heavily carved with statues of great leaders of Judeo-Christian history as well as foliate ornamentation. The last statue on the southeast end of the porch is that of Bishop Phillips Brooks, about whom I wrote in my December post on Phillips Brooks and the Christmas Carol. This is one of five places where you will see the image of this highly charismatic and influential man both around the church he served so well.

The Crowninshield House

H.H. Richardson designed this private home in 1869 for his Harvard friend, Benjamin Crowninshield, three years before he received the commission for Trinity Church. Here he used a design approach called panel brick, which was becoming popular at this time. Panel brick uses the brick masonry of the façade to create decorations through projecting or receding brick panels as well as bricks that are stacked, twisted, indented, or shaped into intricate patterns.

In the Crowninshield House, Richardson also employed ornamental tiles, something not seen in his later structures. These include a round blue-and-white tile, similar to the ceramic work of the Della Robia brothers, set in arches made of brick with alternating rows of bricks that were tarred black after they were laid. The house also sports a row of diamond-shaped stone tiles bordered by tarred bricks. A similar cross over the front door has been obscured by the fire escape that was added when his building became a college dormitory. The columns atop the box-bay entrance are made of twisted and tarred bricks and the sandstone capitals have been carved on the outside—but not the front. No one knows why.

The Back Bay’s Small Treasures

These are only a few of the small treasures that I point out on the Victorian Back Bay tour. There are many, many more.

I’m giving the tour tomorrow at 2:00 p.m. and again on Saturday at 4:00 p.m. Meet me on the steps of Trinity Church in Copley Square and we’ll explore them together. Oh, and the duck and trolley tours won’t bother us once we get past Copley Square because they don’t come into the Back Bay’s residential area at all.