When I wrote a post last month about the Soldiers and Sailors Monument on the Boston Common, with statues carved by Martin Milmore, I didn’t know I had found a connection to not one, but two, cemeteries.

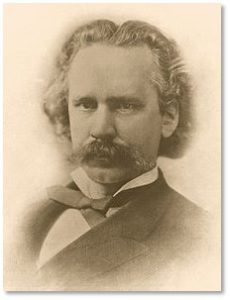

Martin Milmore the Sculptor

Born in Sligo, Ireland, Martin Milmore immigrated to the United States in the 1850s at the age of seven with his widowed mother and several brothers. Unlike most Irish immigrants of the period, he came from a middle-class Protestant family with some financial resources. His father had graduated from university and was a schoolmaster in Sligo.

As a Protestant, Mr. Milmore did not have to contend with Boston’s strong anti-Catholic bias as he grew up. He attended the Brimmer School, from which he graduated with honors, and the Boston Latin School, from which he graduated in 1860. He also took art classes at the Lowell Institute.

From 1860 to 1864 he studied under the sculptor Thomas Ball, working in Mr. Ball’s studio in the Chickering Piano Company building at 791 Tremont Street in the South End. Mr. Ball had established this studio specially to create the equestrian statue of George Washington that looks down Commonwealth Avenue from the Public Garden. The young trainee kept the studio clean and attended the fires as payment for his tutelage. He had his own studio in this space and his work could be seen by Mr. Ball’s many visitors.

Note: The Chickering Piano Company building is still extant. Designed by Edwin Payson, it employed 400 men, was steam-powered, and produced 60 pianos a week at its peak. The building has been converted to the Piano Craft Guild condominiums and lofts.

Sculptor of Civil War Memorials

Trained as a stone carver by his brother, Joseph, Martin Milmore went on to become a brilliant sculptor. In addition to the Soldiers and Sailors Monument, he created Soldiers’ Monuments in Jamaica Plain and Charlestown. He also carved a large granite Civil War memorial at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge.

While he was known as the country’s foremost sculptor of Civil War memorials, Mr. Milmore never served in the Union Army. Without knowing it, I have driven frequently by his Union Soldier in Framingham, MA. While war did not take his life, Martin Milmore died in July of 1883 at his home on Hammond Street in the Roxbury Highlands of cirrhosis of the liver. He was only 39.

Had he not died young, Mr. Milmore would almost certainly have gone on to bigger and greater things. The large statues of Ceres, Pomona and Flora that he carved for the façade of Boston’s old Horticultural Hall (no longer extant) now preside over The Gardens at Elm Bank, the headquarters of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society. Although his work lacked the lyrical quality and emotional force of his famous pupil, Daniel Chester French, he would now be far better known had he left a larger body of work.

Mr. Milmore was buried in Forest Hills Cemetery in Jamaica Plain, along with his three brothers—who also died young—and his mother.

Note: For a much more detailed biography of Martin Milmore, read William P. Marchione’s excellent blog post, “Martin Milmore, Boston’s Great Civil War Sculptor,” on his Local Historian North & South blog.

The Angel of Death and the Sculptor

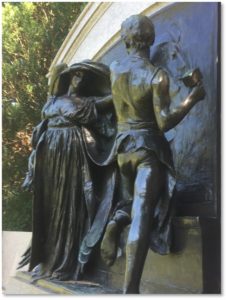

Years after his death, once probate problems had been cleared up, Daniel Chester French created his famous memorial for the Milmore family plot at Forest Hills Cemetery.

Daniel Chester French’s large monument on the Milmore family plot is called “Death and the Sculptor” or, sometimes, “Death Stays the Hand of the Sculptor.” Mr. French depicted a young and vigorous man hard at work, his muscles toned by years of stone carving, as he creates one of his most famous monuments. The hooded and solemn Angel of Death stands to his left. Her right hand holds a bunch of poppies, symbol of sleep. Her left hand arrests the sculptor’s chisel.

Mr. Milmore, wearing a leather apron, appears surprised by the interruption, as well he may have been at only 39. The combination of his astonishment at the end of his life and the angel’s calm but implacable action gives the monument its great impact. One becomes so engrossed in the two figures, however, that it’s easy to ignore the statue that the sculptor is carving. If you look closely, you see the bas relief figure of a full-length recumbent Sphinx, another Civil War Memorial that he carved with his brother, Joseph.

The Memorial Plaque

Although overgrown by ivy, a plaque beneath the granite setting by the Boston Firm of Andrews, Jones, Boscoe and Whitmore says:

Death and the sculptor

“Come, stay your hand,” Death to the Sculptor cried

Those who are sleeping have not really died.

I am the answer to the stone your fingers

Have carved, the baffling riddle that still lingers

Sphinx unto curious men. So do not fear

This gentle touch. I hold dark poppies here

Whose languid leaves of lethargy will bring

Deep sleep to you, and an incredible spring.

Come with your soul, from earth’s still blinded

Mount by my hand the high. The timeless tower

Through me the night and morning are made one.

Your questions answered, your long vigil done,

Who am I? On far paths, no foot has trod.

Some call me Death, but others call me God.”

Martin Milmore’s Sphinx

The American Sphinx resides in another cemetery—Mount Auburn in Cambridge. Commissioned by Dr. Jacob Bigelow, who was instrumental in founding the garden cemetery, it commemorates all those who fell in the Civil War. Dr. Bigelow paid for the statue using his own funds, The Sphinx appears as a recumbent lion with a woman’s head.

She wears a pharaoh’s Nemes headcloth—made in Egypt with blue and gold stripes—that marks the end of an earthly life and the beginning of the afterlife. The head of what is presumably the eagle of liberty projects from its center in place of the Egyptian vulture or the Uraeus cobra. She also has a necklace with a pendant star. The inscription on one side says:

“American Union Preserved

African Slavery Destroyed

By the Uprising of a Great People

by the Blood of Fallen Heroes.”

The other side repeats this dedication in Latin. Sculptor’s marks appear on the right side just under the rear foot and a mark mentioning Dr. Bigelow appears on the left below the other rear foot. The Sphinx faces the Gothic Bigelow Chapel.

Thus, we have a memorial to a sculptor in one cemetery that references a memorial to fallen soldiers carved by that sculptor in another. Many people visit both cemeteries and view the monuments without knowing of the other or the connection between them. While it is easy to miss the Sphinx on the Milmore Memorial, there no missing the great granite original at Mount Auburn.

Finding the Two Statues

Forest Hills Cemetery

Forest Hills Cemetery

95 Forest Hills Ave, Jamaica Plain, MA 02130 Hours: 8:30AM–4:30PM You can find more information about Hours and Directions on the website

To find the “The Angel of Death and the Sculptor” just walk through the neo-Gothic gate and look to the left. Once you have examined it, take some time to walk around this beautiful space and note the other monuments and memorials. Four were carved by Daniel Chester French. You can download a map of the cemetery with famous “residents” and points of interest.

Mount Auburn Cemetery

580 Mt Auburn St, Cambridge, MA 02138

Hours: 8AM–6PM

The American Sphinx is not as close to the Egyptian Revival gate but it is not hard to find, either. From the office (which has maps), just walk straight back toward the Bigelow Chapel. It’s the big neo-Gothic building, resembling a church, that is slightly uphill. The Sphinx keeps an eye on the front door from just across the way.