I first published this post in May of 2016. On this Veterans’ Day,

I think it bears repeating.

Many recent articles have bemoaned how polarized American society has become along with the lack of understanding that populations in different parts of the country have for the concerns of people in other regions. Almost universally they ask, “How did it get this bad?”

Living in Bubbles

Part of the answer to that is political, of course, but that’s not what this post is about. I prefer to deal with another issue: the lack of opportunity for different groups of people to mix, to live with one another, to understand a variety of perspectives, and to form a unified bond as Americans irrespective of demographic distinctions.

Part of the answer to that is political, of course, but that’s not what this post is about. I prefer to deal with another issue: the lack of opportunity for different groups of people to mix, to live with one another, to understand a variety of perspectives, and to form a unified bond as Americans irrespective of demographic distinctions.

We live in bubbles of people who are just like us: economically, ethnically, racially, religiously, and culturally. We see those like us as familiar and right while those not like us as strange and therefore wrong in some way.

Mandatory National Service

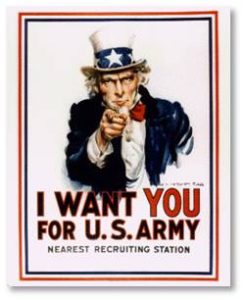

Susanne’s post about how military service in Israel builds teamwork and a unified national culture held a mirror up to just how badly America does at the same thing. When we lost the Draft, we lost more than we thought at the time.

Thus I’m going to write a sentence that my 20-something, Vietnam War-protesting self would never have dreamed of: we need to instate a mandatory national service.

For 33 years, from 1940 to 1973, this country had The Draft—mandatory military service for every able-bodied male between the ages of 21 and 36. Beyond the obvious result of keeping our armed forces well supplied, The Draft accomplished some extraordinary things for American society. I have never served in the military so these observations are purely those of a retired white collar grandmother. I could be wrong but I do have the benefit of historic perspective and I think that military service accomplished the following.

Mixing and Mingling

Conscription forced men (and women volunteers) to mingle and work with one another despite differences of race, skin color, religion, political affiliation, region of the country, accent, or education. We’re all familiar with Hollywood’s version of this: the platoon that includes one of everything, but it’s based on the reality of everyone serving in the military.

Draftees didn’t get to pick and choose who they would share a barracks with, what platoon to serve in, what drill sergeant to train under, or what base they would live on. They didn’t always have a bathroom and no one argued about who would get to use it when they did.

Draftees didn’t get to pick and choose who they would share a barracks with, what platoon to serve in, what drill sergeant to train under, or what base they would live on. They didn’t always have a bathroom and no one argued about who would get to use it when they did.

The military’s job was to turn groups of reluctant, unprepared, out-of-shape and incompetent boys that included head cases, screw ups, air heads and outright juvenile delinquents into soldiers, sailors and Marines. The recruits didn’t have to like it; they just had to straighten up and fly right.

De-Personalization

The services started this process, of course, by de-personalizing the young men and that began with shaving off the hair, beards and mustaches that mark individuality. Stuffing everyone into uniforms came next, which removed all distinctions except those of unit and rank. Then came Boot Camp in which the recruits were often called insulting names like maggots to force them to control their emotional reactions and follow orders even if they hated the man who was giving them.

These days, no one is forced to live with people they don’t like—or think they won’t like—except perhaps in college dorms. We’re typically not exposed to people who Aren’t Like Us and that lack of perspective about how Other People Live allows us to sink deeper into our own group viewpoint. The result is coming to believe that our bubble’s values are the only viable way to see the world.

Gaining Competence

The Draft was called the Selective Training and Service Act for a reason: men who went through military service were trained how do a variety of things, depending on their assignment. They might have learned how to peel a potato and cook for a crowd, wield a shovel and dig a ditch, paint anything that didn’t move, or load and unload a truck.

They all learned how to make a bed perfectly and how to handle a weapon—not a gun—responsibly. In addition, servicemen mastered specialized tasks that they could translate into jobs or careers once they were discharged. But they were all competent and knew how to handle themselves in a crisis.

They all learned how to make a bed perfectly and how to handle a weapon—not a gun—responsibly. In addition, servicemen mastered specialized tasks that they could translate into jobs or careers once they were discharged. But they were all competent and knew how to handle themselves in a crisis.

Contrast that with whiny, self-indulgent, young people who can’t hold a tool, complete a chore, take care of themselves, make decisions, or honor a commitment. They allow their emotions to boil over, sometimes fatally, at the slightest provocation. We see these “man boys” on the big screen and laugh but, really, a grown man with the maturity of a seventh grader is not funny.

Learning Responsibility

In the military, you learn to be responsible as well as competent. No one protects you from yourself—instead you learn how to do things the right way, the first time.

You’ve never handled a weapon before? We’ll train you how to do that until you understand what that weapon is for, how to clean it and care for it, and—most importantly—when and where to use it.

You’ve never handled a weapon before? We’ll train you how to do that until you understand what that weapon is for, how to clean it and care for it, and—most importantly—when and where to use it.

We’ll teach you that a weapon is not a toy, that you should not wave it around just to feel important and that you shouldn’t point it at another human being unless you plan to use it for a good reason. When you do, you’ll know how to hit your target and how to avoid collateral damage.

- You think that being an adult means running your mouth without regard for the consequences? We’ll train you how to behave in a mature fashion, along with when to respond to a situation, and what to say when it’s relevant and important to say it.

- You think that the world is a safe place where everyone knows you’re special? We’ll teach you how to expect the unexpected, how to respond to a crisis, and how to keep yourself and others safe. Both Laurence Gonzales in “Deep Survival” and Amanda Ripley in “The Unthinkable” note that servicemen and veterans often do well in a crisis situation precisely because they have been trained to expect the unexpected and to react immediately when civilians freeze — and die.

Oh, by the way, you’ll also learn that taking care of the people around you can be more important that putting yourself first.

Do We Need the Draft Again?

Except for the men and women who volunteer to serve in the military, we lost these components of American culture when the Draft went away. And we need to fix that. Do I think we should re-institute The Draft? Not exactly. I’ll put my recommendations in tomorrow’s post.

In the meantime, if you want to add things you learned in the military or tell me what I got wrong, just put a comment in the space below.

Related Posts:

One other point I forgot to mention – I don’t think it’s necessarily a good comparison of Israel’s mandatory conscription service to our previous draft history. Israel, being about the size of New Jersey, is far more homogenous in terms of diversity than the more vast United States is today I would think. Lots more dynamics to consider here.

I think you made a lot of good points, but re-instituting the draft is probably not a good long term idea. I would’ve gone had I been drafted, but I was in college breaking my butt trying to get an engineering degree and paying for more than half of it by myself. I was fortunate to always have gotten high numbers in the draft lottery those years, but I was sweating bullets for awhile! Also, if I didn’t cut it in engineering school, the school would’ve dutifully notified the local draft board, and I’d have gotten a free one-way ticket to China Beach. Luckily that didn’t happen for me, but I know of a bunch of others where it did.

We have a son who will process out of the Army next month after four years as an artillery officer. One of the main reasons he will not even remotely consider this as a long term career: the poor quality of the leadership ( old boys club, outdated military strategy) and the lack of good soldiers in general. As he said “you don’t want them next to you in a fox hole.”

I thought you were positive on military leadership.

I am, but its becoming a rarity. Listening to the stories from our son I am disheartened and discouraged. He tells me that many of the soldiers opting to stay in are below par, with no better options when you consider the salary, benefits and retirement. He liked and respected all of his boot came and advanced training leaders, but out in the real world he was disillusioned.

I have mixed feelings on this.

I read a statistic that, percentage-wise, fewer and fewer people have military service. I think that’s a catastrophic thing for our society.

On the flip side, conscripts generally don’t make the best soldiers – volunteers do.

So the root question: are we doing this for “society” or for the best military we should have?

The military brass agree with you about volunteers making better soldiers tan conscripts. But we can think outside the box on this one. I’ll do that in tomorrow’s post.