“My name is Ozymandias, king of kings. Look upon my works, ye mighty, and despair.”

— Percy Bysshe Shelley

Regular readers of The Next Phase Blog have learned a lot about Boston’s street names. From 1708 when the city formalized the names of its streets, until now, we have seen the city’s streets named for a wide variety of things and people. We have streets named for seafood and trees, geologic features and waterways. You can drive on street names of patriots, battles, founders, seasons, the sun and moon, and businessmen.

Street Names and Politicians

All of those street names add character and layer history over the city. One group of street names I don’t think we need, however, is that of politicians. I used to believe I was the only person to hold this opinion until I read a Boston Globe column by Jeff Jacoby.

Mr. Jacoby is a conservative Republican and I rarely agree with his opinions, but he has written several columns for the Boston Globe that made me want to stand up and cheer.

They’re So Vain

Here’s a paragraph from a column entitled, “They’re So Vain, They Probably Think This Bridge is About Them:”

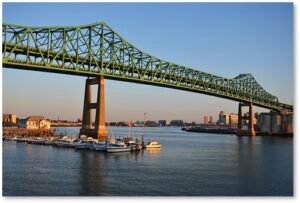

“You can hardly turn a corner in Boston without coming across a building or bridge or park or roadway named for a politician or a politician’s relatives. The Moakley courthouse. The Fitzgerald Expressway. The McCormack federal building. The Rose Kennedy Greenway. The Saltonstall state office building. The Tobin Bridge. The O’Neill Tunnel. The Menino Pavilion. The Hynes Convention Center. The statues of Kevin White and James Michael Curley. Some politicians have two, three, or even four of these ‘monuments to me,’ as they’ve been dubbed. Besides the federal courthouse named for former Congressman Joe Moakley, there is a Moakley park, a Moakley academic center, and a Moakley medical building. There’s even an Evelyn Moakley bridge named for his wife.”

At ground level, we also have Lomasney Way, the McGrath and O’Brien Highway, and other street names that put politicians in every address.

The Political Ozymandias Complex

And therein lies the problem. The politicians who hold the purse strings and greenlight a public project then have the ability—and the chutzpah—to name that project after either themselves or someone in their family. Calling this unseemly makes for a vast understatement. Not only does it bestow honor on someone who volunteered to be a public servant, it exposes the man and the city to the harsh glare of history.

One might think that a smart politician would look at several examples and decide to keep his name to himself. (I say “he” because, well, read the list above.)

Maurice Tobin and the Bridge

The Tobin Bridge from Charlestown to Chelsea got renamed for former Boston Mayor and Massachusetts Governor Maurice J. Tobin, a man whose administrations were marked by corruption.

Example: Under his watch, Barney Welansky, owner and manager of the Cocoanut Grove nightclub had free rein to bribe officials in order to ignore building codes, municipal permits, and capacity limits. He paid off politicians and inspectors with money, drinks and free meals for years.

It did not end well. On, on the night of November 28, 1942, a fire broke out at the Cocoanut Grove and killed 692 people in 30 minutes. Neither Mayor Tobin nor any of the bribed officials in his administration paid a price for their negligence and corruption.

Before Gov. Tobin’s name got stuck on it, the bridge had a perfectly good name: the Mystic River Bridge for the waterway it crossed. Cool, right? They even named a movie for that river. Likewise, the Moakley Federal Courthouse had previously been known as the Fan Pier Courthouse for the commercial railroad tracks that once fanned out to the piers where ships docked. Neither needed to be renamed for a politician. And did we really need the Black Falcon Terminal to be renamed the Raymond Flynn Cruiseport?

Dudley Square to Nubian Square

Boston’s Dudley Square held the moniker of Thomas Dudley, British Colonial Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. He held office in 1641 when the colony first legally sanctioned slavery. Activists say his family went on to benefit from the slave trade.

Dudley Square was an especially offensive name for a largely Black section of Boston. A five-year campaign finally succeeded in stripping Gov. Dudley’s name and renaming the place as Nubian Square.

Digging into the backgrounds of some of the politicians who have left their brand on Boston might well uncover other unsavory facts. Someone tempted to slap his name on one of Boston’s streets might look at the rise and fall of Yawkey Way—from Jersey Street to Yawkey Way and back to Jersey—as an illustration of what to avoid.

Political Self-Idolatry

Boston isn’t the only city to indulge in what Mr. Jacoby calls “political self-idolatry” of course. It happens across the country. He asks, “Can’t we call a halt to this taxpayer-funded ego-stroking of people who are supposed to be public servants, not public deities?”

We can and we should. I would go a step further and make it illegal for a politician to put his or her name on any street, building, facility, or public work of any kind that was built with public money.

Why should the taxpaying public put up the construction funds but then have no say in what the facility is called while someone who draws a government paycheck puts his name up in lights? If they want to put their name on something, let them raise the money to build it.

An Honor Roll of Deserving People

After all, Boston’s history holds far more deserving people that we could honor. My favorite roadway in Boston is the Ted Williams Tunnel, named for a baseball player who showed up and worked hard at what he did so well for his entire career.

After all, Boston’s history holds far more deserving people that we could honor. My favorite roadway in Boston is the Ted Williams Tunnel, named for a baseball player who showed up and worked hard at what he did so well for his entire career.

I will add my nominations to Mr. Jacoby’s list of the non-political Bostonians we could put into a public-naming database:

The Candidate List

- Julia Child: the woman who introduced French cuisine to America through her cookbooks and television show.

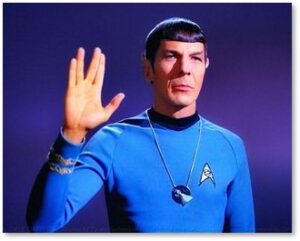

- Leonard Nimoy: the actor who brought Star Trek’s Mr. Spock to life and made an international symbol of a gesture he saw in a West End synagogue.

- Horatio Alger: the author of scores of inspirational novels.

- Clara Barton: founder of the American Red Cross.

- Leonard Bernstein: the great composer, conductor, and teacher.

- Christa McAuliffe: the first civilian sent into space, who died in the 1986 Challenger disaster.

- Winslow Homer: the renowned illustrator of the Civil War battlefield and painter of New England scenes.

- Eli Whitney: who invented both the cotton gin and the American system of mass-production manufacturing.

- Lydia Pinkham: inventor of her eponymous Vegetable Compound, the first patent medicine created specifically to relieve women’s complaints, which male doctors either ignored or treated with painful surgery.

- Charles Bulfinch: the early American architect who designed the State House in which many of these politicians work, and who became the third architect of the United States Capitol.

- Prince Hall: the abolitionist and leader in Boston’s free black community, who founded Prince Hall Freemasonry and lobbied for education rights for African American children.

- Cornelia Wells Walter: the first female editor of a major daily newspaper, the Boston Evening Transcript

There are, of course, many other local men and women of achievement who go unnoticed while Boston’s white male political class erects monuments and names street names for their own imagined greatness. I’m sure you could add more names this list without any trouble.

The Catch-22 Problem

Can we fix the situation? Here’s another relevant quote from Jeff Jacoby’s opinion:

“Once upon a time it was understood that public entities shouldn’t be named for still-living politicians. Some admirable officials were even content to let their life’s work be their monument. How quaint that seems in our age of fame junkies and self-idolatry, when for too many politicians it’s all about the monument, and not nearly enough about the work. Reversing that trend would admittedly be a daunting task, but refusing to name things after politicians would be a good place to start.”

We know the problem, of course. To make illegal this scam of using public funds to build private monuments, one needs a politician to enact a law. That’s asking them to act against their own self-interest, and often, their own self-aggrandizement. Is any politician in this state willing to step up and do the right thing?

If so, send me an email. I’d love to speak with you.