Before I forget, I want to write my last piece for “The Next Phase” of 2015, which is now my first article for 2016, as I did not finish it until New Year’s Day, about Alzheimer’s Disease. Most people blanch when talking about Alzheimer’s, and with good reason. It, something it has affected, or both, are fatal 100% of the time.You may recall the lines spoken by Jaques the Fool in Shakespeare’s “As You Like It”

“Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion,

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

None of us wants to play this role.”

Separating The Wheat From The Chaff

As you might imagine, the results produced by Alzheimer’s research cover many different disease pathways. Opening all these doorways produced a lot of either wrong or contradictory information.

As you might imagine, the results produced by Alzheimer’s research cover many different disease pathways. Opening all these doorways produced a lot of either wrong or contradictory information.

For example, many of you are probably familiar with the terms “amyloid plaque,” “neurofibrilary tangles,” and “tau.” For years, scientists thought that one or more of these caused Alzheimer’s, and a lot of work went into trying to prove one or another the culprit.

New Concepts for Alzheimer’s Disease

It is only within the last two or three years that other concepts have been drawing a lot of interest: Overactive immune systems, chronic inflammation, excitotoxicity, and looking at Alzheimer’s as Type III diabetes. All of these are interrelated as follows:

The brain contains immune cells called microglia. They are like Roombas, sweeping through the brain to clean up germs. Normally, they go about this work in a normal state; however, when they are activated by injury, infection, environmental poisons, etc., they produce cytokines and chemokine, which are inflammatory agents.

Microglia also produce excitotoxic agents like glutamate, especially when the brain, as often happens in older people, doesn’t generate enough energy for optimal brain function. When the brain’s energy is reduced, neurons, dendrites, and synapses become more sensitive to excitotoxic agents.

Microglia also produce excitotoxic agents like glutamate, especially when the brain, as often happens in older people, doesn’t generate enough energy for optimal brain function. When the brain’s energy is reduced, neurons, dendrites, and synapses become more sensitive to excitotoxic agents.

The brain uses glucose for energy. But, if the inflammation and excitotoxicity have disabled or destroyed brain cells and connections, then there are fewer mitochondria to “burn” the glucose for energy. The remaining cells become glutted with glucose. The body reads this as more glucose to be processed, so the pancreas makes more insulin. Insulin’s job is to help glucose enter cells and find mitochondria. Because the insulin can’t do its job, the condition can develop into insulin resistance which can morph into what some scientists call Type III diabetes.

An important point to remember is that low-level inflammation can exist in a body for decades before injury, heavy metals, poor diet, or other stimuli can cause it to ignite. Specifically for Alzheimer’s, this low-level inflammation can start the processes that lead to the kinds of amyloid plaque, neurofibrillary tangles, and tau that, in some individuals, will progress to Alzheimer’s. Why it doesn’t happen in all people who develop plaque is a mystery.

Four Steps To Slow Down Or Prevent The Process

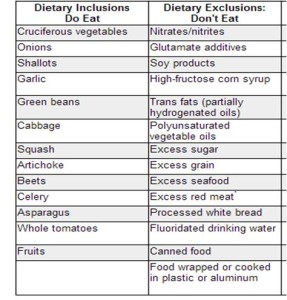

Step 1: Eat a good diet, one that does not promote inflammation. Here is a chart containing lists of nutritional Dos and Don’ts:

Step 2: Get exercise, which has been shown to help repair the brain.

Step 3: Take supplements: Hawthorn, Silymarin, R-Lipoic Acid, N-Acetyl Cysteine (NAC), a multivitamin, and plenty of fiber. Some folks will add Vitamin D3 and Magnesium. However, without the proper foods and regular exercise, you will be reducing the value of the supplements, which work best in bodies that take in healthy food and drink and that stay active.

Step 4: Laughter is healthy, too. With that in mind, here is a joke about forgetfulness:

Dan runs over to Paul’s house. “Paul, you’ve gotta help me!”

“Sure,” replies Dan. “What’s the problem?”

“I can’t remember a damn thing! I open the refrigerator, I forget why. I go into a room, I don’t remember what I’m doing there. Driving I sometimes forget where I’m going.”

“Relax, Dan. I had the same problems. But I saw a doctor. He taught me some mental exercises, prescribed a few supplements, and now”—he snaps his fingers—“I’ve got a memory like a 20-year old.”

“Great!” What’s the doc’s name?” asks Dan.

“He taught me a great way to remember names. First I have to picture an object, like a flower. In this case, the flower is bright red, has many petals, and the stems have thorns. It’s . . . called . . . a . . . rose!”

Then Paul calls out, “Hey, Rose, what’s the name of that doctor I saw?”

They say when you get older you forget three things.

You forget names, you forget places… and I forgot the third one.