This post completes last week’s article on Navigating Boston’s Architecture.

The Troubled Government Service Center

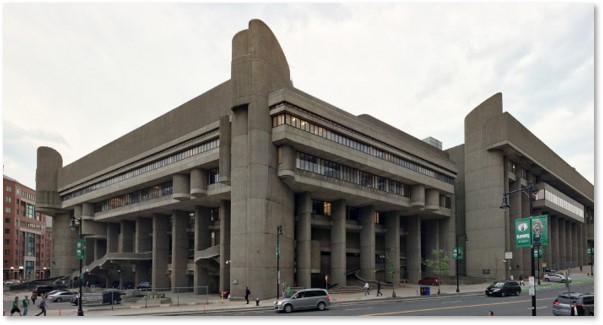

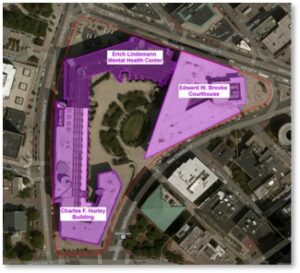

This structure, erected from 1966 to 1971 on the rubble of Boston’s old West End has a troubled history. An extension of the nearby Government Center, the Brutalist concrete structure, designed by Paul Rudolph, consists of two buildings. The Charles F. Hurley Building and the Erich Lindemann Mental Health Center are connected by an open courtyard. A third element, a tower, was never bult.

Although the complex remains unfinished, it has generated controversy for decades. Now the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, which owns GSC, has taken action to solve at least some of the problems. The Boston Globe reports that four developers have filed proposals to redo the Hurley Building.

The GSC’s Multiple Problems

Unfortunately, the State has chosen not to make those proposals public. Why unfortunate? Because emotions run hot about Mr. Rudolph’s complex. If you are not a fan of Brutalism—and many Bostonians are not—this massive concrete structure with its bush-hammered corrugations is massively ugly.

Second, the over-three-acre Government Service Center is enormous; better suited to a suburban office park surrounded by woods than to a prime piece of downtown real estate. Facing the brick north slope of Beacon Hill as it does, the Government Service Center looks like Castle Grayskull dropped into the heart of Boston. Raised from street level, it looms out of proportion to the city around it.

And, like a castle, it stands aloof and separate. Pedestrians have no way to walk through it from one street to another and no reason to go into it. The courtyard was supposed to be a “bustling public plaza” but bustle doesn’t happen in a place so walled off most of the public doesn’t know it exists.

To say the Government Service Center is not pedestrian friendly is an understatement. The concrete superblock devoid of street-level windows has blank vertical walls that might as well post signs reading, “Go away.”

Unworkable and Dangerous

Last, and certainly not least, the people who work in the complex have no love for it. As the comments in the Globe’s article reveal, the buildings are cold, dark, damp and confusing. Their personal experience says more about how unworkable the buildings are than any architectural review.

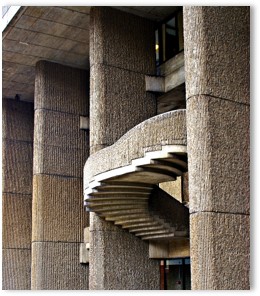

Worse, they can be dangerous. Consider that the Lindemann Mental Health Center can be accessed by high and exposed cantilevered staircases with low railings.

Those corrugations, bush-hammered by hand at great expense, are so sharp that just brushing up against them can shred clothes and draw blood. No mental health expert would consider those features suitable.

Demolish the Hurley Building?

I’m not a fan of demolishing an architecturally significant building because it’s ugly or dysfunctional. Tastes change, usually in 50-year cycles. The Victorian home so fashionable in the 19th century is considered ugly by the 20th and desirable once again by the 21st.

Surely, no decision on the GSC’s fate has to be all or nothing. I would like to retain part of the Government Service Center, including some of the towers and those graceful staircases, and demolish the rest. That would keep some of Paul Rudolph’s vision in the city while correcting his worst mistakes.

Put up something suitable to the neighborhood and buildings that invite people in. Tear down those sheer curtain walls and build sidewalk-level shops and restaurants. Perhaps install a museum behind the Hurley Building’s enormous windows. Make the most of what works; then create structures that actually perform the necessary functions of keeping their occupants warm, dry and able to do their jobs.

Unfortunate Secrecy

That’s why it’s unfortunate that the State has not revealed the competing proposals. Especially since this is not the first go-round for redeveloping the Hurley Building. Secrecy does not work to the State’s advantage here.

A look at what the four developers are suggesting would give both neighborhood residents and GSC employees a chance to agree, disagree, or suggest improvements. That might tamp down the outspoken criticism detailed in the comments and wild theories about what the future might hold for Paul Rudolph’s Government Service Center.

Meanwhile, I think it’s a sad commentary that the Hurley Building and the whole Government Service Center are the antithesis of what the demolished West End truly was. Diverse, vibrant, noisy, and bustling, it was beloved by those who lived there. The government destroyed the West End to save the city and here, at least, they got a concrete castle in its place.