Guest Author: Seth Kaplan

Until last Thursday, 26 November 2015, just one look at those slimy oyster body parts, still dripping mystery liquid over the edges of barnacled half shells, would cause my gorge to rise. But as I was in France for the first time, I determined to face all gastronomic challenges with equanimity if not enthusiasm.

Picture the scene: Only 13 of us banded together to make the two-hour bus trip and subsequent cross-harbor excursion to Arcachon, an elegant summer resort town. We took a boat across the Arcachon Basin — one of the largest oyster growing and harvesting areas in France, if not the world — to the small village of Claouey.

We hiked from the bus through the winding, picturesque streets of the village until we arrived at a set of weather-beaten stone buildings, in continuous use for centuries for one purpose: Growing, harvesting, and transporting oysters.

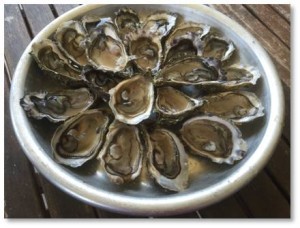

A burly, barrel-shaped, grizzled fellow, whose rolling stride hinted at a life on the water, came out to greet us. He arrayed us around picnic tables that bore platters of fresh oysters on the half shell, bowls of quartered lemons, artisanal buttered bread, bottles of white wine, and plates and small forks.

The burly gentleman turned out to be the owner of the enterprise. He launched into a lengthy discourse in French (most of which I could understand, thanks to five years of French from grades 7-12 and a sixth year in college; the guide’s translation showed how much I had remembered—and forgotten) covering the history of oystering, his business, and the science of raising oysters.

The demonstration included handling the metal lattices on which the baby oysters are planted, examining the salt-water-filled tanks in which the oysters reach maturity, showing the proper way to shuck an oyster, and lastly, of course, tasting the fruits of the owner’s, and our, labors.

The Power of Analogous Dining

I had anticipated that my culinary bravery would now be tested, but one point the owner made lowered the risk for me. As he explained how to shuck an oyster, he demonstrated how to cut the little muscle that connects the oyster to its shell. When I saw that, the light dawned.

“Oh, it’s just like eating a mussel or a clam!” I realized. I eat both of those without any trouble.

Casting aside my trepidation, I served myself three oysters in salt water on the half shell, squeezed fresh lemon juice over them, and slurped the first one, even chewing a bit before swallowing.

A Gastronomic Adventure

Sacré bleu! What a delicious, nutty, salty flavor! I downed the other two as quickly as I could so as to continue the taste sensation without appearing to be a gourmand. Then, I loaded my plate with three more and some beurre et pain, and washed them down with two glasses of excellent vin blanc.

“This will be our snack, or appetizer, before motoring across the harbor to the restaurant for lunch,” said our guide, an effusive British woman who had married a Frenchman and lived in France for many years. The restaurant, L’Escale, sits on the tip of a peninsula in Cap Ferret, one of the great celebrity summer vacation settings.

As we walked back to the bus, none of us could stop exclaiming over the great taste of the oysters and how the entire experience fit into the week of gastronomic adventures we enjoyed in Bordeaux. While there were undreamed-of dining pleasures awaiting us on our return to our Viking River Cruise ship, the Viking Forseti, and at a château the following evening, we all agreed that the alfresco setting, convivial atmosphere, and the simple, yet delicious, oysters and accompaniments made this day one of the highlights of our week-long trip.